‘I am sorry,’ Goode tells city in MOVE talk | 1986

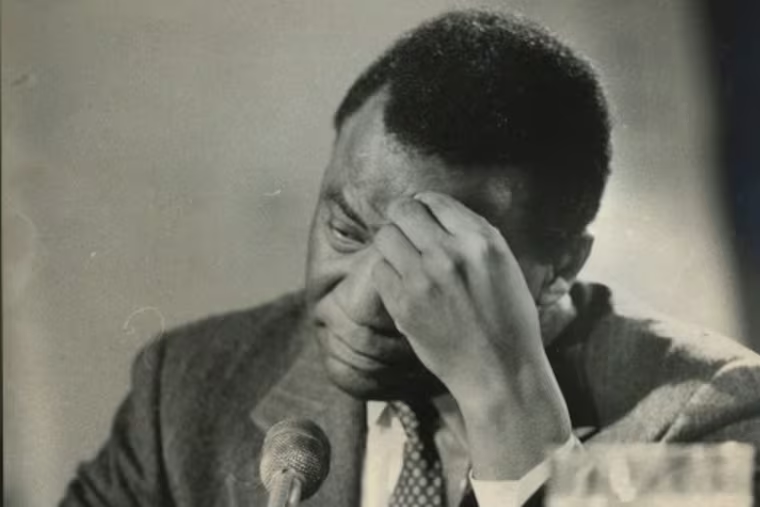

Goode, whom the MOVE commission criticized as “grossly negligent” for approving the police assault, said May 13 “was the most tragic day in my life.”

This story appeared in The Inquirer on March 10, 1986.

Mayor Goode, in an unemotional television appeal last night that he billed as a “heart-to-heart talk” with Philadelphians, apologized again and again for the way his administration handled the May 13 siege on Osage Avenue — and pledged that the harshly critical findings of the MOVE commission would ’'serve as a blueprint” for a government overhaul.

As he did late last week, Goode emphasized that he was grieved deeply by the deaths of five children who, along with six adults, were trapped in the MOVE house as flames engulfed it and destroyed 60 other houses.

The fire was triggered by a police bomb dropped from a helicopter after MOVE members could not be routed from their two-story rowhouse in a gun battle in which police fired 10,000 rounds of ammunition.

Goode, whom the MOVE commission criticized as “grossly negligent” for approving the police assault, said May 13 “was the most tragic day in my life.”

“Each day, I live with its memories. I think often of the five children and six adults who lost their lives,” Goode said in the seven-minute speech, also broadcast live on radio. “I wish that May 13 had never happened — but it did, and I am sorry for that.

“I am, as a father, especially grieved by the loss of the children. When I think of the MOVE children, I weep for them and for their families. A part of me died with those children, and to their families, and to all of you, I say I’m sorry.”

While Goode spoke of his feelings, he was impassive and showed little emotion during the speech, which he read from a TelePrompTer.

As he did in an interview late last week, Goode steered clear of any mention of plans to seek re-election next year. A week ago, Goode said there was ’'nothing connected with the MOVE event” that would alter his hopes for a second four-year term.

Goode last night limited his remarks about his future to issuing a plea for ’'your help and for your support to make Philadelphia all that it can be.”

’'I am not asking that you forget May 13 — I cannot,” he said. " . . . I ask all of you who are concerned about our future to join me in achieving our goals. Together, we can make it work.”

Nor did he announce specific changes designed to prevent a disaster in the event of another confrontation between the city and an armed radical group. Such measures will be announced by Goode today at an 11 a.m. news conference to be televised live from City Hall.

The mayor’s decision to make a purely personal appeal drew praise as well as criticism last night.

“It was the only thing that he could say: ‘Sorry,’” commented Inez Nichols, one of the Osage Avenue residents whose homes were destroyed by the MOVE fire.

Temple University Law School Dean Carl E. Singley, who served as special counsel to the MOVE commission, said Goode demonstrated “a quality of humaneness” in his address. “What most people wanted to hear today was how the mayor felt as a human being and as a chief executive about that very, very tragic event,” he said.

But Goode’s political rivals, such as state Sen. Vincent J. Fumo, contended the speech was too little, too late. Fumo said it should have been delivered within days of the confrontation.

And other observers said the speech fell far short of its advance billing. Robert S. Hurst, president of Lodge 5 of the Fraternal Order of Police, characterized it as “a seven-minute segment of misty-eyed sentimental mush.”

“I was taken aback . . . ,” Hurst said. “I thought the whole purpose was to answer some charges.”

William B. Lytton 3d, the MOVE commission’s staff director and general counsel, said Goode “didn’t say anything.”

“What surprises me,” said Lytton, “is that having the opportunity to address the citizens of Philadelphia . . . and to really get into some specifics and talk about the changes that are going to be made, he didn’t do that. And I’m a little disappointed.

“He has spoken to us this evening from his heart — and I accept that,” Lytton said. “And I think what’s needed now is to speak to us intellectually, to speak to us governmentally, and to get down and do those things that have to be done — or else we’re going to have another tragedy.”

Singley, interviewed after he took part in a televised panel discussion on the mayor’s address, said he felt the brief speech was not “the appropriate forum” for the mayor to respond to the commission’s findings.

However, Singley said there were “unanswered questions from the standpoint of how decisions got made” that Goode has an obligation to answer. Singley said the mayor should respond during the news conference today or in writing.

“His failure to do so will create more difficulties for him in the long run than perhaps even the decision that took place on May 13,” he said.

In the speech, Goode indicated he would outline today a planned reorganization of the city departments that played a role in the MOVE confrontation and their responsibilities. Such changes could affect not only the Police and Fire Departments, but also the city’s Department of Licenses and Inspections, the Water Department and the managing director’s office.

Last night’s speech, broadcast from the studios of WPVI-TV (Channel 6) on City Avenue, had been viewed as a turning point in his governmental career. Political allies and rivals alike said that if the speech were successful, it would help Goode begin putting MOVE behind him. If not, his administration could remain mired in the aftermath of the confrontation for the 20 months remaining in his term, they said.

The mayor delivered the speech one week after the draft findings of the commission were published in The Inquirer. The MOVE commission, which Goode appointed to investigate the May 13 confrontation, released the report officially on Thursday. All week, Goode refused to comment on the specifics of the report, saying he needed time to formulate his response.

» READ MORE: MOVE panel airs its findings

The commission said that Goode and his top aides displayed a “reckless disregard for life and property” in planning the siege; that Goode himself, in approving the plan, was “grossly negligent” and “clearly risked the lives” of the five children who died — deaths that the commission said appeared to be “unjustified homicide” and should be investigated by a grand jury.

On the day Goode set aside to respond, members of his church in Southwest Philadelphia, and those in other black congregations across the city, prayed for spiritual guidance for Goode.

Last night, about 30 people lined the walkway outside the WPVI studio and waved signs that read, “Mayor Goode, We Love You,” and chanted, “Goode is our man.”

One of the supporters, hospital workers Local 1199C spokesman David Fair, said the demonstrators wanted to show “there’s a lot of support for him out in the community, and I think it’s not being accurately reflected in the media.”

Inside the studio, Goode was joined by his wife, Velma, their two older children, Muriel and Wilson Jr., and several members of his cabinet and staff. He refused to talk to reporters during a photo session before the speech, and was hustled out a side door to a waiting car within three minutes of concluding the speech.

In his speech, Goode said — as he did in the days following May 13 — that he ’'was determined that . . . there would be no injury or loss of life” when the city tried to arrest MOVE members. He also said he accepted responsibility for “all the actions of city government — the good . . . and the tragic.”

“I thought the plan would work,” Goode said. “We all know it did not. In trying to save lives, lives were lost. In attempting to rescue a neighborhood, it was destroyed by fire.”

Contributing to this article were staff writers Russell E. Eshleman Jr., William W. Sutton Jr., S.A. Paolantonio and Robin Clark.