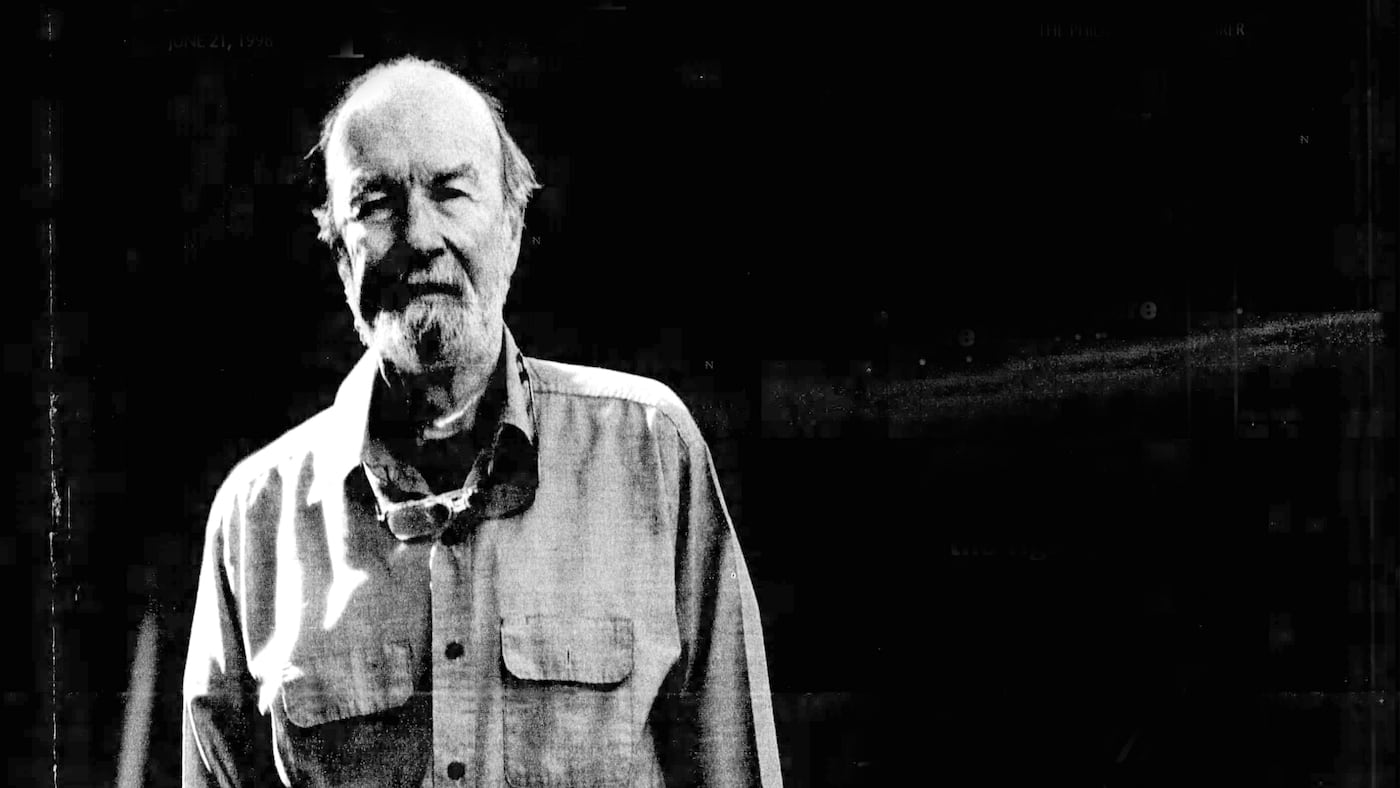

Pete Seeger and Me: Remembering the man, the music, and his legacy

Original publication date: June 21, 1998

The success of A Complete Unknown, the Bob Dylan biopic starring Timothée Chalamet that’s up for eight Oscars on Sunday, has created new interest not only in Dylan, but also Joan Baez, played by Monica Barbaro, and Pete Seeger, portrayed by Edward Norton.

Anyone aiming to understand Seeger, the folk music Johnny Appleseed, regarded as a kind of secular saint for his undying belief that music can make the world a better place, could do no better than to read this profile by David O’Reilly originally published in The Inquirer in 1998.

O’Reilly, who covered religion at The Inquirer for 22 years and is now an award-winning magazine writer and budding novelist living in Wellsboro, Pa., had deep connections with Seeger, who died in 2014 at 94. In the 1970s, O’Reilly worked on the Clearwater, Seeger’s 106-foot sloop that launched in 1969, and continues to operate as a floating classroom on the Hudson River spreading a gospel of environmentalism.

Driving a Ford Pinto, Seeger once randomly picked up a hitchhiking O’Reilly in 1972. O’Reilly’s son Chris went on to work as a shipwright on the boat “and his girlfriend is a former captain of the ship, so we’re sort of a Clearwater family,” O’Reilly said recently.

“He really is my hero. He was back then, and he still is.”

O’Reilly was pleased to see Seeger’s “decency is manifest” in A Complete Unknown. He recognized his friend in Norton’s performance. “I thought he captured Pete’s voice and body language pretty darn well. The roll-up of the sleeves just to the bottom of his elbows, that’s exactly how Pete always wore his shirts. I was pretty gratified by the whole film.”

Writing “Pete Seeger and Me” for the Inquirer Magazine, in 1998, “I just thought — and I do to this day — that his values are absolutely admirable. He was a man of astonishing principle, going back to the ‘40s and ‘50s. He was the one who introduced Martin Luther King to ‘We Shall Overcome.’ I wanted people to know about who he was.”

— Dan DeLuca

Off the phone at last, Pete Seeger springs from a back bedroom and calls out a greeting. “Who’s that guy with the gray hair?” he wants to know. I laugh; it’s been 17 years since last we saw each other. I point out the white in his beard and what’s left of his hair, and he laughs, too.

“Hey, is it warm enough in here?” he wonders, glancing around the kitchen of his converted barn in Beacon, N.Y. I start to say it’s fine, but he doesn’t wait for an answer. “Think I’ll put another log on,” he says, and disappears.

His wife, Toshi, who has lived with his inexhaustible energy for 54 years, shakes her head. We follow Pete into the bedroom office, assuring him the house is warm enough, but he is already crouching before the woodstove with a split oak log in his hand. “Too long,” he decides, and as he reaches toward the woodpile for another, the log bumps against the stove. Bonk.

“Hey!” he exclaims, turning round to us. “Hear that? Why, it’s a musical log!”

He taps it again, producing another resonant bonk. Pete grins. “E flat. I’m gonna save this one. Think I’ll put it with my instruments,” he announces.

Toshi and I look at each other. Who else but Pete Seeger would make a log sing?

His delight in that log makes me smile. As I watch him scurry through his house in early April, at 78 still eager and skinny as a schoolboy, I am struck once again by the near-mystical intensity that has propelled him to modern legend. Part Johnny Appleseed, part Thomas Paine, part Walt Whitman, Seeger for six decades has used words and music to challenge and celebrate what it means to be a principled citizen.

It is he who popularized “We Shall Overcome,” turning it into the anthem of the civil rights movement. It is he who wrote what is perhaps the finest anti-war song of this or any other century, “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?”

And from his pen comes the reflective, hymnlike “Turn, Turn, Turn” from the Book of Ecclesiastes, with its gentle reminder that there is “a time to be born, a time to die ... a time for every purpose under heaven.”

Without him, the world would not know “Guantanamera” or “Wimoweh” or “If I Had a Hammer,” and hundreds more Seeger songs and melodies and discoveries that send souls stirring, toes tapping, minds thinking, and whole concert halls singing.

But to me, he is something else again: a man who helped me make sense of the world and showed me a way to live at a time, and in ways, my own father could not.

After 60 years of singing on picket lines and in hobo jungles and at peace marches and summer camps, his famous tenor voice no longer has the strength to rouse concert halls with such trademark tunes as Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land,” or the traditional “John Henry,” or his version of “The Bells of Rhymney.”

“Now I just call out the words and the audience sings along,” he says with a shrug of resignation.

Across the kitchen table, though, his voice is still clear and resonant. Ask him a question or tell him a story and he nods eagerly, cocks his head, and launches into a reply that might skip from the population explosion to his back-to-nature experiments as a boy, to a verse of gospel music, to Einstein, to a discourse on the Bruderhof, a modern-day Christian commune on the upper Hudson River that supports itself making wooden toys.

“I think the biggest revolution the human race has ever seen is going to be a moral revolution, where we realize that our fate depends on each other,” he says between sips of miso soup and bites of corn bread. It is the social gospel he has preached for six decades.

“Someday there’s gonna be tens of millions of small organizations, and we’ll disagree about so many things it’ll be hilarious: ’Save this! Stop that!’ But we’ll agree on a few basic things like: ‘Better to talk than shoot, right?’ And when words fail, we won’t give up. We’ll try other things: arts, numbers, melodies, boats, you name it.”

It’s an earful. Yet it all coheres somehow around a vision of humankind in harmony with itself and the natural order.

Like many Americans, I first met Pete Seeger without knowing it. As a child I sang “This Old Man,” one of the countless folk tunes he discovered and introduced to a national audience. I delivered newspapers after school with “Kisses Sweeter than Wine” playing from my transistor radio, and sang “If I Had a Hammer” and “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore” at Boy Scout camp in the early 1960s.

Then, at the end of that same anguished decade, I was among the half-million Vietnam War protesters marching on Washington as Seeger sang his own “Last Train to Nuremburg” from the steps of the U.S. Capitol.

I didn’t know then I was looking for a father-hero, of course. But as I entered my 20s, America seemed scary, unstable. I’d played by the rules as a youngster: I’d been an altar boy, a paper carrier, and the senior patrol leader of my Scout troop.

Then came John Kennedy’s assassination, and Alabama sheriffs turning dogs on voting-rights demonstrators, napalm, the My Lai massacre, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy and four peace demonstrators at Kent State University, and Richard Nixon’s corrosive dishonesty. My country seemed to be going mad.

My own father didn’t have answers. A product of the Great Depression who grew up in modest circumstances — his father had died on his 6th birthday — he went to college on a scholarship, edited his college newspaper, wrote radio plays, captained a B-26 bomber in World War II, and traded whatever writerly journalistic ambitions he had for a life as a New York corporate public relations director.

Often sullen and inexplicably angry, Dad was not a guy who heard music in the bonk of a fire log. His politics were moderate-Democrat of the Adlai Stevenson variety, and he modeled for his three sons honesty, fidelity in marriage, hard work, and a love of writing.

But as I entered adulthood I wanted a new model, a new paradigm, a new way to live. And in 1971 I found one aboard Clearwater, a 106-foot replica of the great single-masted sailboats that plied the Hudson River in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Clearwater had sprung from Seeger’s lyrical imagination just a few years before; after reading a book about the bygone Hudson River sloops, he hit upon the idea of building one — “something to rally people around a cleanup of the Hudson,” he proposed to a neighbor. His idea inspired a broad-based fundraising effort, and in 1969, Clearwater’s 65 tons splashed down the ways of a Maine shipyard and sailed south for the Hudson Valley.

The plan for Clearwater was impossibly naive: The sloop, with its 108-foot mast and huge, gaff-rigged mainsail, would sail into towns along the Hudson with a crew of folk singers. They would put on concerts at the water’s edge and, between songs, talk about river pollution and urge people to get involved.

Visitors could come out for a sail, too, and members of the Clearwater organization could volunteer to crew for a week, living aboard and helping the permanent crew hoist sails, coil lines, steer, cook, and wash decks. The only cost then was $10, for food.

“Nothing in America works that way,” I thought when I heard of this. But I joined, and quit my miserable job answering mail for Moneysworth magazine so I could crew. I figured I’d find another job when I got back. On Oct. 15, 1971, I met the Clearwater at South Street Seaport in Manhattan.

As I caught my first whiff of its tar and wood smoke I supposed I was merely stepping onto a quaint, old-fashioned sailboat. But in truth I was stepping into the moral universe of Pete Seeger: a rustic, collective, optimistic, egalitarian, not-for-profit universe more reminiscent of the utopian Shaker and Hutterite and Oneida religious communities than of anything envisioned by Marx and Lenin.

I spent that week on Clearwater sailing twice a day out of Yonkers, N.Y. We taught river ecology to schoolchildren with seine nets and microscopes, showing them the life that teems in the Hudson, and I sensed I had found a home. Life aboard that grand, creaking sloop, with its wood cookstove and block-ice refrigerator, its stained-glass windows and laughter and homemade music — all in the name of cleaning up the Hudson — satisfied my hunger for community and worthy purpose.

Then one evening, toward the end of that week, Seeger himself came by as some college-age visitors were on deck, strumming guitars. He sat down to listen, and after a while one young man led the group in “Get Together” by the Youngbloods: “Come on, people now, smile on your brother, everybody get together, try to love one another right now.” We all sang along, and when we were done, Seeger said: “I do believe that that’s the nicest version I’ve ever heard of that song.”

The short-haired young man who led it was stunned. “Gosh, thank you,” he stammered. “That was the first time I’ve ever sung in front of anyone!”

“So this is Pete Seeger,” I thought.

That winter and through much of 1972 I visited the sloop on weekends, sanding or varnishing or scraping decks for a meal and a chance to sail, but in all that time, I never said more than a few words to Seeger. At summer’s end, I moved from New York to Connecticut, where I did odd jobs and occasional assembly-line work. Then, on a freezing November afternoon, as I was hitchhiking the interstate through Danbury, a green Ford Pinto pulled over. I ran up to it, pulled open the door, and there he was behind the wheel.

“Hop in,” he said. It was apparent he didn’t know me — he just picked up hitchhikers. But we talked about Clearwater, and I learned that as a young man Seeger had thumbed and ridden the rails across the country with his banjo over his shoulder, learning new tunes, helping organize unions, singing for a sandwich and a glass of beer. “I remember what it’s like to be on the side of the road with my thumb out,” he said.

He loved to talk. As I sat listening to him in April in his farmhouse overlooking the Hudson, with Clearwater sailing toward Newburgh across the way, I heard the same stream of ideas that had poured out of him that day, and later, when we were driving to concerts or washing dishes in the wood smoke of Clearwater’s galley.

“Let the billionaires go their corrupting and disastrous course; the only thing that can save this world is small business. Of course, big companies make cheap paper and cheap computers and big airplanes, so we can travel, and that’s good. But there needs to be all sorts of little things: small businesses, small scientific and social and educational organizations. .... ”

I joined the permanent crew on May 3, 1973, and lived aboard Clearwater for most of that year. In the decade that followed I served as a member of Clearwater’s board of directors and, for a while, its president. Seeger visited the boat every few weeks, and though he rarely stayed overnight, he always helped with chores, washing or drying dishes, coiling lines, or chopping wood — a favorite task of his. I can see him on the dock at Ossining, swinging an ax to an old prison tune: “Take this hammm-ERRR!” Whap! “Take this hammm-ERRR!” Whap!

But he was essentially a private man who kept his distance behind a wall of words, someone who gave off more light than warmth. I understood this: A lot of people asked a lot of Pete. But I admired him for the same reason his unauthorized biographer, David King Dunaway, did — because, as Dunaway told me the other day, “I found no inconsistencies in the man Pete Seeger and the public persona.”

He lived by the simple values he preached. I remember the afternoon in 1973 when a concert promoter sent a big, black limousine to the sloop to take Seeger to a performance in New York. He was horrified when the uniformed chauffeur explained that the Cadillac was for him: He literally clutched his head and groaned. When he learned none of the crew had a plain old Dodge or VW bus he could borrow, he beseeched us to ride with him in the limo. With three or four scruffy sailors along, he figured, a limo might not look so pretentious.

I used to joke that communism would have worked in this country if we had been a nation of Pete Seegers; he was always pitching in for some cause or other — whether it was building a log canoe for the children of Beacon (it sank), or putting on a benefit concert for a tiny local library.

In 1974, I hit him up: I had written a booklet for Clearwater explaining how new environmental laws were cleaning up the Hudson and celebrating the renaissance of the commercial shad fishery. Who better than Seeger to write a preface?

“Would you do it?” I asked one day. He winced. “I think I’m destined to go down in history as a writer of prefaces,” he said with a brave smile. I discovered I had added one more chore to his already overburdened writing schedule: He devoted a day each week to answering his mail, which sometimes arrived in cartons. (It still does.) But he spent an hour at a typewriter and wrote me a preface.

Several weeks later, Toshi and I were in the Manhattan offices of Seeger’s manager, printing and collating 500 copies of the Shad Book — “With an Introduction by Pete Seeger” — on a clunky old silk-screen printer. (Everything about Clearwater is pretty rustic.) We finished around midnight, too late for my train back to Connecticut, so Toshi invited me to come home with her “if you don’t mind sleeping in a barn.”

Around 1 a.m., we drove up their long, rutted dirt drive. The night was black as could be. Just then we saw a man come out of the house. It was Seeger, barefoot in pale-blue pajamas, unaware he had a visitor; he’d come out to open the car door for his wife.

Perhaps people in China hear the name “Pete Seeger” and think of his version of “We Shall Overcome,” which pro-democracy students sang in Tiananmen Square as they lay down before the tanks. Maybe union organizers know him as the arranger and popularizer of “Which Side Are You On?” and “Union Maid.”

And if the peace lasts in Ireland, perhaps Seeger will be remembered there for the achingly beautiful new recording of “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” sung in alternating verses by a Protestant from the North and a Catholic from the South.

But my memory of Pete will always include his coming out to greet his wife at 1 a.m. For me that small kindness, when he thought there was no one but his wife to see it, lent authenticity and heart to the face on the album cover.

Pete’s father, Charles Seeger, was one of the nation’s first scholars of ethnic music. A Harvard-educated aristocrat who wore ascots and smoking jackets, Charles Seeger was nonetheless a member of the “Wobblies”: the radical, leftist Industrial Workers of the World.

“Their idea,” Pete recalled in April, “was: ‘Sign up everybody in one organization, and then we’ll just call a big general strike, and the next day the world will be run by the workers.’” Their scheme sounds “infantile” to Seeger now, but Charles’ concern for the poor and for workers, and his belief in the transformative power of music, shaped his third son profoundly.

I met Charles Seeger in 1978, at his home in Bridgewater, Conn. — a town I happened to cover as a reporter at my first daily newspaper. Bearded, white-haired, with a squeaky voice and gold-rimmed glasses, he sat by the fire in a wing chair and for fours hours took me on a galloping horseback tour of Western civilization, beginning with socialism and moving somehow from 12-tone music to Greek architecture, Venetian sea battles, astronomy, Franklin Roosevelt, Charles Ives, farming, cubism. I hardly got a word in.

What made it all the more charming was seeing so much of Pete in the tilt of Charlie’s head, his crooked teeth, that bony forefinger wagging skyward, punctuating an endless fugue of ideas.

When Pete was 16, Charles took him to a folk music festival in Asheville, N.C. There, he heard some rustic, homemade country songs with “a hard, honest edge” that felt truer than the Tin Pan Alley pop tunes of the day. He fell in love with folk music, and with the five-string banjo, which became his trademark.

At about this age Pete also read Thoreau’s Walden and announced to some chums that he was going to be a hermit when he grew up: It was the only way to live without moral compromise, he said.

“What kind of morality is that?” one boy replied. “Be pure and let the rest of the world go to hell?”

“I’ve never forgotten that argument,” Seeger says. “I decided they were right. I had to get involved.”

At 18, Seeger entered Harvard, got bored, and quit after two years to work as a union organizer. Around 1939, he met legendary Oklahoma folk singer Woody Guthrie: a hard-drinking, two-fisted ex-farmer bankrupted by the Depression, as rough-hewn and Midwestern as Seeger was polite, intellectual, and Eastern.

But they were kindred spirits, angry with the suffering of the Depression and the social inequities of capitalism. Together they rode freight cars with little more than their instruments on their backs, singing at lumberjack camps and on picket and bread lines.

In 1941 Seeger and Guthrie put together a group called the Almanac Singers. Their first big performance, in May of that year, was for 20,000 striking Transport Union Workers at Madison Square Garden. Seeger sang the opener, “Talking Union”:

If you want higher wages let me tell you what to do;

You got to talk to the workers in the shop with you;

You got to build you a union, got to make it strong;

But if you all stick together, boys, it won’t be long...

The crowd roared for more.

But anyone preaching a society where workers had more economic muscle than owners sounded subversive to the FBI, which began a file on Seeger. Though he served as a private in World War II, he was deemed “suspicious,” and his file grew fatter with every workers’ rally he sang for.

On Aug. 18, 1955, he was ordered before the Un-American Activities Committee of the House of Representatives (HUAC) and asked if he had ever sung for Communist causes.

“I am not going to answer any questions as to my association, my philosophical or religious beliefs, or how I voted in any election or any of these private affairs,” he replied. “I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this... ”

His refusal, citing the First Amendment rights of free speech and assembly, was the career equivalent of Socrates’ drinking hemlock: heroic death. He was charged with contempt of Congress and sentenced to 10 years in prison, tarred as a Communist, and blacklisted by TV and radio — even by some of the unions he had championed for so long.

Jailed briefly, he was freed on appeal. He went underground, singing instead for college audiences and summer camps and in rented halls for as little as $25.

Life on the road took him from Toshi and their two (later three) children for weeks at a time. “We ate a lot of beans in those days,” she recalls. But it was a creative time, too; he wrote the original, short version of “Where Have All the Flowers Gone” in the summer of 1956.

And around 1960 his modified version of the old Methodist hymn, “I’ll Overcome Some Day” — written by the Rev. Charles Tindley of Philadelphia in 1903 — emerged as “We Shall Overcome,” the great civil rights chant that would become an international song of liberation. Not until 1968, when the Smothers Brothers invited him to sing “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” — his devastating allegory of America’s descent into the Vietnam War — did the networks reluctantly lift their ban. Seeger began to emerge from exile as a kind of mythic figure to many of my generation.

Seeger’s enemies had long memories, however. Twice in 1973, someone cut our dock lines while we were tied up overnight at a little town across the river from West Point. And somewhere I still have the red-printed leaflet that a member of the John Birch Society thrust into my hand at a concert, denouncing him as “Stalin’s songbird.”

The 1990s have been kind to “Stalin’s songbird,” however, canonizing him in ways once unthinkable: Harvard honored him; he won a Grammy Award; was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame; and in 1994, was awarded both a National Medal of Arts and a Kennedy Center Honor for lifetime achievements.

Watching the broadcast from the Kennedy Center, I shook my head in wonder, amused at seeing Pete in his late father’s 1922 tuxedo, and cheered by Arlo Guthrie’s stomping tribute to Seeger, “This Land Is Your Land.”

Then, when Guthrie and Joan Baez and Paul Winter and Garrison Keillor and a dozen other artists held hands on stage and began to sing “We Shall Overcome,” I lifted my 5-year-old son, Christopher, into my lap. It was way past his bedtime, but I wanted to connect him somehow with that music, that man, that time in my life.

“Why are you crying, Daddy?” he wanted to know. It was hard to explain.

This spring, Appleseed Recordings, based in West Chester, Pa., released a two-CD anthology of 39 Pete Seeger songs recorded by some 50 musical luminaries including Bruce Springsteen, Bonnie Raitt, Jackson Browne, Odetta, and Judy Collins.

“My reason for making this CD is just that his songs have gone around the world and empowered so many people,” producer Jim Musselman, a public interest lawyer, explained several weeks ago in an interview at his home office. It’s a sunny room cluttered with musical instruments and Seeger memorabilia, including every record he’s ever made.

“His songs are his children, and he’s not going to be touring the world again. So I wanted to take his children around the world — and also to the next generation.

“Exposure to Pete changed my life,” says Musselman, 40, who tells of having a “kind of religious experience” at law school in 1978, when he read Seeger’s testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

“I was shocked. I’d never learned about the McCarthy era. And I sort of sat up and said, ‘Wait. This guy was doing something important as an American, standing up for constitutional rights.’”

Within a year Musselman had “decided to work for social justice,” and joined forces with consumer rights activist Ralph Nader. He spent much of the 1980s doing community organizing around the country, helping to beat back a threat by General Motors to relocate its plants to Mexico. Later, he spearheaded the long, successful campaign for federally mandated airbags in passenger cars.

“If not for Pete, I would have been a corporate lawyer and not led half the fulfilled life I’ve had, working for social justice,” Musselman says. “So I like to say we have Pete Seeger to thank for airbags, and I’m serious. I think his life is testimony to how one rock in a pond can create a lot of ripples.”

Seeger — who’d rather sing his songs than listen to them — is gratified by Musselman’s effort. “I’m a very lucky songwriter to have other people singing my songs,” he says. “And who knows? Some of them may be heard in the future.” If there is one. He’s not so sure.

“I think — I hope — we have another 100 years, but the entire world will have to realize the danger we’re in.”

Just as a younger generation of Germans once demanded to know if their parents had done anything to thwart the Holocaust, he said, future generations will demand to know what we of the late 20th century did to halt the disastrous depletion of the world’s natural resources.

“The question that’s gonna be asked of CEO after CEO after CEO,” he said — smacking the kitchen table on each CEO — is: “‘When do you stop being a CEO and start being a grandparent? What are your grandchildren gonna say about what you are doing?’”

It was a rare flash of fierceness.

“Do you ever get discouraged?” I wondered. He laughed softly.

“Every night around 9, I say the hell with it, and go to bed,” he replied. “But the next morning I jump up with a million ideas for projects I can’t complete.”

How did Pete Seeger change me? He confirmed my sense that there is much more to life than making money. And through Clearwater I got a glimpse of the interconnectedness of all living things. I lived communally for several years, became a journalist, and nowadays write mostly about religion, with its ideas of morality, duty, and community. Organized religion doesn’t always have the right answers, I’ve noticed. But, like Seeger, it asks the right questions.

And with my wife and son and daughter, I live by the Delaware River; my sailboat is moored nearby.

But I’m my own father’s son, too. My politics are more Adlai Stevenson than Karl Marx. I have a white clapboard house in the suburbs and commute to work in a necktie. Like him, I’m a writer, and I hope that some day my children will say that I modeled the virtues of hard work, faithfulness, and honesty.

In the last years of my father’s life the cloud of depression that had hung over him for so many decades lifted, thanks to antidepressant medicine, and we discovered him to be a man filled with joy and sunlight. So did he. He loved to tell of the time he was resting in bed, recovering from one of his heart surgeries, when my Christopher, then 3, crept upstairs to his bedside without our knowing it and said, “I love you, Papa.”

When Dad died unexpectedly in May 1995, the hardest moment for me was telling Chris the news as I walked him home from kindergarten: I can still see him pausing at my words, then looking into my face, and then bending over in tears.

My brother, charged with making the funeral arrangements, decided Dad would be buried in the little churchyard down the road from my parents' farm in Hunterdon County. It wouldn’t have been my choice; my wife, Birnie, and I were married in that church, and it was always a joy for us to see it on the way to visiting Mom and Dad.

After the final graveside prayers, the family and friends walked back toward the farm, just as they had done on my wedding day. “Do you think I could ring the church bell, Dad?” Chris whispered. I supposed yes, that no one would mind.

As Birnie and our baby daughter, Claire, walked on, Chris and I slipped inside the empty church. I found myself in the same dark basement hall where I had stood so nervously in June 1984.

Up in the choir loft, Chris and I found a rope dangling from the ceiling. He pulled: clang. Pulled again: clang. And again and again, and despite the solemn occasion, we laughed at how the rope lifted him off the floor on each upswing.

Downstairs, Chris came with me as I walked up the aisle and gazed for the first time in 11 years at the spot where Birnie and I had said our wedding vows. I was trying hard to feel the joy of our wedding so Dad’s burial here would not eclipse the memory of that day.

Then I noticed the Bible on the altar, and wondered what it was open to. I stepped up and saw in large letters: Ecclesiastes.

Could it be? I scanned the page and saw, down to the right, the words Pete had set to music.

“For everything there is a season, and a time for every purpose under heaven:

“A time to be born, and a time to die...

“A time to love, and a time to hate...,”

In that moment I felt my father had at last met Pete, and that they, and Chris and I, were being held together in something larger than ourselves.

I took Chris by the hand, and we started for the farm.

Davidcoreilly@gmail.com