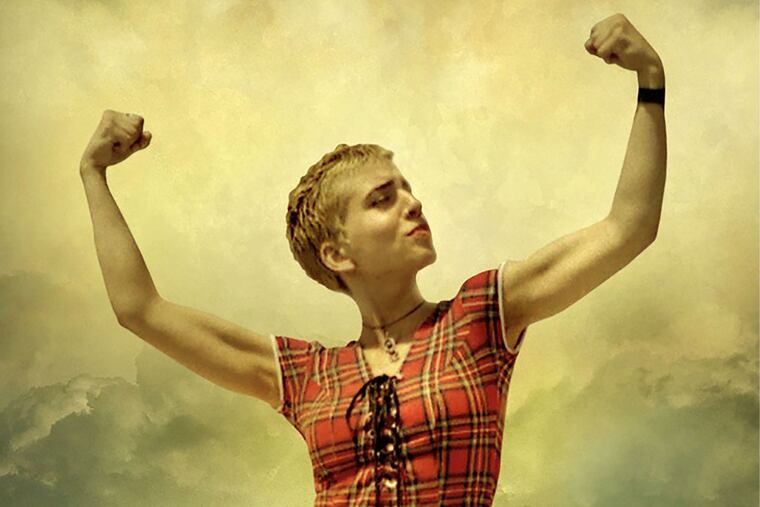

Ani DiFranco’s 'No Walls and the Recurring Dream’: Deep and thoughtful, from an artist eager to connect

The XPN favorite and indie icon recounts her life up to 2001 and stops there. It's a "making of" story, about a woman raised and living alternatively, in her life and music alike. It's a tale of long rides in beat-up cars, musical idols, and songs arising from her advocacy and iconoclasm.

No Walls and the Recurring Dream

A Memoir

By Ani DiFranco

Viking. 320 pp. $28

Reviewed by Karen Iris Tucker

Ani DiFranco has always been an idealist and an iconoclast.

She was lured by but never signed with major labels, opting instead for the grueling yet freeing path of remaining independent on her own imprint, Righteous Babe Records, which she started in 1990. She is a folk singer, in some ways akin to the classic mold of her friend Pete Seeger. Yet she also melds into her mix African rhythms, jazz, and funk. Her feminism, bisexuality, furious guitar-picking, and gorgeous acoustic melodies have inspired many a young woman to go shirtless at her concerts. She is also a Grammy Award winner, and now, at 48, a married mother of two.

Her new memoir, No Walls and the Recurring Dream, is part feminist and social-justice manifesto, part bracing road story. She tells us about the artists who influenced her — Seeger and Woody Guthrie, Thelonious Monk and Joan Armatrading among them — and the experiences that shaped her (for starters, an unusual childhood).

Then, when she gets to 2001, DiFranco pulls back. Readers looking for a definitive account of her life should be forewarned: "I only ever intended this book to be the ‘making of’ story," she says at its close.

But what an origin story. DiFranco grew up in a log-cabinlike home in Buffalo that literally had no walls inside, save for the bathroom. Every thought DiFranco had was outside the box because there literally were no boxes — or rooms, as was the case. DiFranco’s parents’ bed was visible from her own.

She began taking guitar lessons with a musician who came to be a lifelong friend. At the tender age of 9, she essentially became his sidekick: “We hung out in bars and coffeehouses, busked on the street, foraged in thrift stores.”

By 14, she was writing songs. A year later, DiFranco became an emancipated minor and moved out of her family home. She confides that to pay the rent, she relied on the $300 she got as an underage dependent on her father’s Social Security.

After attending Buffalo State College, DiFranco ultimately fled for a sublet in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District. She worked odd jobs, including as a nude model. Simultaneously, she managed to write an album’s worth of songs, which she recorded on digital audiotape in 1990. She began hearing from fans, mostly young college women who contacted her by snail mail. Many were invitations to play at very low-budget events. DiFranco was eager to connect: “I was searching, through music, for the experience of family,” she writes.

So she set out on the road and slowly worked her way into the hearts of music lovers — one gig at a time — often traveling in beat-up cars, with a female or male adventurer-lover in tow.

These experiences are both heartening and bracing. She learned how to handle the misogyny in club venues unfamiliar with her style of lyrics and sound. There was also the dangerous matter of being a woman alone and in transit. DiFranco recounts several perilous situations. She wrote the song “If He Tries Anything” for her 1994 album Out of Range in the aftermath of one of them: “We are wise wise women / We are giggling girls / We both carry a smile / To show when we’re pleased / We both carry a switchblade/In our sleeves.”

For the most part, however, DiFranco approached her travels with wonderment and abandon -- and often met intriguing, colorful characters along the way. They include Prince, who attended a show she played in 1999 in his native Minneapolis. She recalls the moment the rock icon rolled down the window of his limo: “There he was, lounging on the white shag-carpeted floor of the car in the most vivid purple silk chemise, looking up at me with eyelashes flapping like butterfly wings. ... My face was bare, but Prince was sporting full base and powder. I immediately dug the flip of the script. There we were, both inhabiting our own brand of androgyny, smiling at each other.”

A deep and thoughtful current runs throughout DiFranco’s memoir. She’s a longtime activist, and her book highlights the value and power of speaking up: “With any heart, and with a solid basis of mutual respect, you can go toe to toe in fierce debate with someone and then shift gears when the meeting or class is over and relate once again as friends,” she writes. “We can make room for each other to make mistakes, we can enter uncomfortable and even adversarial spaces, and then we can come back to a hand-shaking stasis and even laugh together.” Ani DiFranco — idealist and iconoclast.

Karen Iris Tucker is a journalist in Brooklyn who writes primarily about genetics, health, and cultural politics. She wrote this review for the Washington Post.