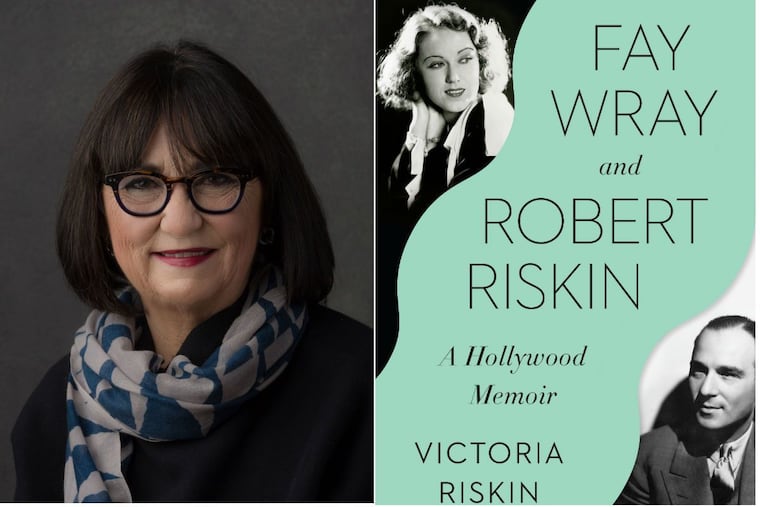

‘Fay Wray and Robert Riskin’: Lifelong love between ‘King Kong’ heroine and ‘It Happened One Night’ author

She rose to fame on the strength of her screams in the hand of a giant gorilla. He wrote some of the best-loved movies of all time. They met late in life and stayed in love for the rest of their time on earth. Their daughter tells their story.

Fay Wray and Robert Riskin

A Hollywood Memoir

By Victoria Riskin

Pantheon. 416 pp. $30

Reviewed by Dennis Drabelle

Fay Wray, heroine of King Kong and many other films, and screenwriter Robert Riskin, author of It’s a Wonderful Life and many other famous films, didn’t find each other until he was in his 40s and she her mid-30s. Wray had been married to screenwriter John Monk Saunders, an alcoholic philanderer, and Riskin had had affairs with movie stars Glenda Farrell, Carole Lombard, and Loretta Young. But for the relatively few years they had together, Wray and Riskin were the love of each other’s life.

Wray (1907-2004) grew up in a Mormon family with lots of kids and little money. Riskin (1897-1955) was the son of immigrant Jews who weren’t very well off either. They both scored early and big in Hollywood, Wray as one of the few stars to weather the transition from silents to talkies, Riskin as a writer whose interest in depicting ordinary Americans made him a natural collaborator with director Frank Capra.

Victoria Riskin tells us that, for all that her mother owed to King Kong, Ann Darrow was not her favorite role. That was Mitzi in The Wedding March (1928), one of the extravaganzas that sank Erich von Stroheim’s directing career. Stroheim envisioned the film, his ultimate attempt to conjure up the glorious Vienna of his youth, as an eight-hour epic to be shown in two parts on successive nights, and he labored over it with an almost crazed perfectionism. Before releasing The Wedding March, the studio cut it by two-thirds, and the surviving version is even shorter. Even so, Victoria Riskin says it’s her favorite of her mother’s films, too, because it showcases “her beauty and innocence encircled by filmmaking elegance from a time gone by.”

In her daughter’s telling, Wray took a sensible approach to stardom. She earned it and had fun with it, but she put it aside when something she considered more important came along: taking care of her husband and children. In contrast, we hear about her good friend Dolores del Rio, a movie star who safeguarded her beauty by “never drinking [and] smiling sparingly to avoid wrinkles.” To prove the point, Victoria has included a photo in which her mother smiles toothily while, at her side, del Rio registers amusement at about the same wattage as the Mona Lisa.

Robert Riskin went to Hollywood as a moderately successful New York playwright. He was hired to write scripts for Columbia, then a mainstay of Poverty Row, as the cut-rate studios were called collectively. The bane of a screenwriter’s life is to slave over material that doesn’t get greenlighted, but according to his daughter, "in his first two years at Columbia, [Riskin] wrote entire screenplays or the dialogue for nine films; all nine went into production." Capra, too, was under contract with Columbia, and a few years after Riskin went nine for nine, the pair won Academy Awards for their work on It Happened One Night (1934).

The Capra-Riskin partnership generated more hits and Oscars: Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Lost Horizon, You Can’t Take It With You, and Meet John Doe. And although Riskin did not script the two Capra movies that arguably have held up best – Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and It’s a Wonderful Life – they are heavily indebted to his style and philosophy.

In his later years, however, Capra cast himself as the sole begetter of any film he had directed. Justifiably annoyed by this slighting of her father’s contributions, Victoria Riskin went up and introduced herself to Capra at one of his film festival appearances. She got no satisfaction.

Her father was long gone by then. In 1946, he’d suffered a stroke. He died nine years later without ever being fully himself again. Researching and writing this book has given Victoria Riskin – and her readers – two related pleasures: getting to know the man who championed the little guy on film and remembering the woman who screamed life into a Fay Wray doll.

Dennis Drabelle is a former contributing editor to the Washington Post Book World. This review originally appeared in the Washington Post.