‘First’: The principled, flinty, historic rise of Sandra Day O’Connor

A country-club politician from Arizona, she endured the sleights and inequities facing women in the legal profession and rose to the top of it, becoming the first woman on the Supreme Court and joining in some of the court's most historic decisions.

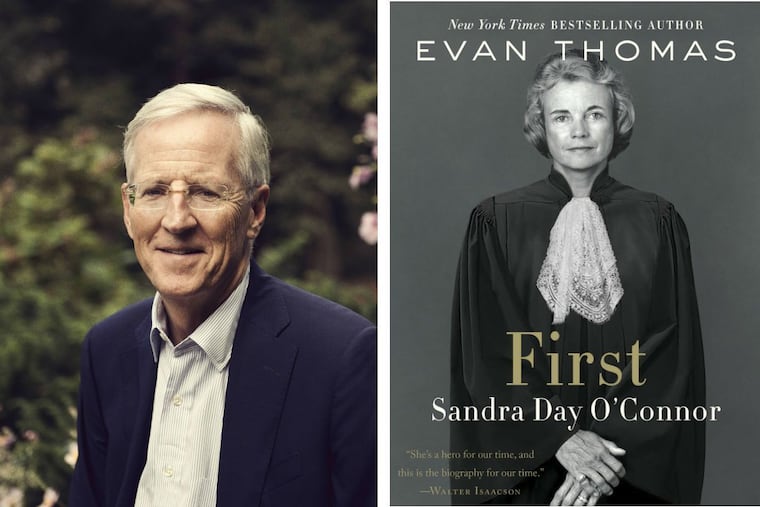

First: Sandra Day O’Connor

By Evan Thomas

Random House. 476 pp. $32

Reviewed by Julie Cohen

A major biography like First by Evan Thomas draws its power not only from the people and events it depicts but also from the culture into which it’s launched. The white-hot polarization in the age of Trump makes Sandra Day O’Connor’s preference for cool civility and compromise seem especially appealing. And this era’s struggle for women’s rights, energized by the #TimesUp and #MeToo movements, makes this the right time to take stock of the country club cowgirl who managed to climb higher than any American woman had before.

On Aug. 19, 1981, President Ronald Reagan made good on a campaign promise to appoint a woman to the Supreme Court. O’Connor got the call and breezed through her confirmation with a 99-to-0 vote.

That O’Connor found herself the highest-ranking woman ever in American government was no accident. Thomas vividly sketches the attributes she used to clear the high barriers to female ascendancy: a knack for brushing past insults, relentlessness belied by a pretty smile, an almost superhuman level of energy, and, not least, a heroically supportive husband. John O’Connor was a successful lawyer in his own right but willing to take a backseat if it meant helping his wife achieve her lofty goals.

This list of assets will sound familiar to Ruth Bader Ginsburg aficionados. (Though, unlike the kitchen-averse RBG, SDO could whip up a tasty salmon mousse when the need arose.) While Ginsburg in her pre-justice days distinguished herself by fighting to secure gender equality under the Constitution, O’Connor was no flaming feminist. If she had been, the Reaganites surely would have looked elsewhere. As a politician eager to distance herself from women’s libbers, she addressed a Rotary Club with the evocative line: “I come to you with my bra and my wedding ring on.” In the State Senate, O’Connor played a key role in striking down hundreds of Arizona laws discriminating against women, but she didn’t put her political weight behind passage of the Equal Rights Amendment. After the Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade opinion, she voted against a resolution calling for an antiabortion constitutional amendment but supported key measures restricting women’s access to abortions.

It was the same style of compromise - some might say fence-straddling - that O’Connor would employ as a Supreme Court justice. Some legal scholars have criticized her for seeking to decide cases on narrow grounds, leaving larger constitutional issues unresolved. In Thomas’ more generous interpretation, O’Connor’s judicial “minimalism” flowed naturally from a realpolitik she’d honed as, well, a real politician.

O’Connor was temperate on abortion rights cases, resisting numerous attempts by her conservative colleagues to strike down Roe but not issuing the ringing endorsement of reproductive freedom that liberals might have favored. Her split-the-difference standard: States can regulate reproductive rights so long as their rules don’t place an "undue burden" on a woman seeking an abortion. In Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey (1992), which she co-authored with Justices David Souter and Anthony Kennedy, O’Connor’s "undue burden" standard became the law of the land.

First does give us a real sense of Sandra Day O’Connor the human being. Cinematic scenes from her upbringing on the family ranch find young Sandra changing a tire all by herself as she struggles to get the chuck wagon to the cowboys before cattle-branding time. Thomas shows how well her flintiness served O’Connor in adulthood. She faces down Stage 2 cancer and a mastectomy with minimal self-pity, doing chemo on Fridays so she could be back on the bench for Monday oral arguments (a regimen passed on to the equally flinty Ginsburg when she, too, got cancer).

Thomas also reveals O’Connor to be likable and quirky, a woman who yelled, “Hot diggity dog!” when she hooked a trout and who got a charge out of Reese Witherspoon in Legally Blonde. The scenes of O’Connor retiring early to help care for her husband as he struggles with Alzheimer’s are poignant, the news of her own diagnosis with that same brutal disease even more so.

Thomas gives O’Connor the credit she deserves. As he suggests, even for those made uneasy by her sometimes-pallid support for Roe v. Wade, or nauseated by her ruling with the majority to cut off the Florida recount in the 2000 Bush v. Gore case, we owe her some respect. Without O’Connor’s crucial fifth votes, both legalized abortion and affirmative action could well have lost their protection under the Constitution. And her strong work through a quarter-century on the Supreme Court paved the way for Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and the others who will follow.

“The first step to getting power is to become visible to others, and then to put on an impressive show,” O’Connor said in a 1990 speech (later quoted admiringly by Ginsburg). “As women achieve power, the barriers will fall . . . And we’ll all be better off for it.” To which so many women - millennial and older, progressive, and conservative - might say in unison: “Amen, sister.”

Julie Cohen is the director of the Academy Award-nominated documentary “RBG,” along with her filmmaking partner Betsy West.