‘Adèle’ by Leila Slimani: An ultramodern woman, all by herself

This skillfully turned novel gives us nothing we expect. Clearly, this is intentional, and clearly, this is brave. It's not a fun read, though, or a world I want to be in.

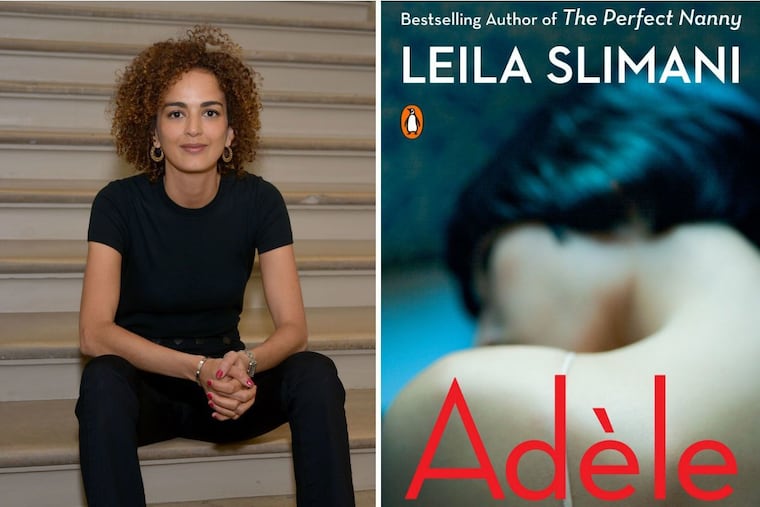

Adèle

By Leila Slimani

Penguin. 240 pp. $16

Reviewed by John Timpane

Leila Slimani is a Moroccan-born writer now living in Paris. She is currently the toast of the Francophone world, thanks to her novel The Perfect Nanny, which, after winning the Prix Goncourt in 2016, became an international sensation last year. Adèle, a novel she wrote before Nanny, is now in English. Any Slimani novel is a major event. However, in the United States, at least, a lot of reviewers don’t like Adèle.

This novel triggers our expectations — about novels, about sex and psychology, about women — and frustrates them. The Perfect Nanny, in its own way, also led us right up to many treasured assumptions … only to bypass or reverse them, leaving us to fend for ourselves in a new, ruthless world. So with Adèle.

Adèle is a sexual compulsive. First seen, she is sweating, tetchy, all but dying to find a random bed partner. A married career journalist living in Paris, she does this all the time. She deceives her husband, Richard Robinson, a successful doctor. She deceives Lauren, the closest thing to a friend she has. “Adèle has been good” is the book’s caustic opener, and she tries, but the effort wrecks her.

Richard is too bourgeois and unimaginative for her. “And yet she does love him,” we’re told. “He is all she has in the world.” (You can just see heads exploding at those sentences.) Biggest of all ironies, in Richard she has what she wants: “He had to take deep breaths whenever he looked at her. … He loved to watch her live; he knew by heart every little gesture she made.”

It’s Richard who, when he discovers the truth, insists on seeing Adèle’s behavior as symptoms of a disease: “He would prescribe the right medicine. He would save her.” Shudder.

Though there’s controversy over whether true “sexual addictions” exist, at least in the same sense that, say, opioid addictions do, there are plenty of recognized sexual disorders. What many of them have in common is that they are power plays; their unfortunate sufferers are driven to use people. Here is the reversal that strikes some as objectionable: Adèle wants to be used, be looked at, be seen and treated as an object. This extends to being physically abused.

Even more infuriating (to some), causes and reasons are absent. If Iago in Othello is motiveless malignity (evil without a reason), Adèle is pathology without etiology. We do meet her unloving mother, and we learn of her young adulthood punctuated by abuse (or what I consider abuse, although it’s seemingly consensual). The narration, however, seems uninterested. All we have is Adèle, alone; the term ultramodern solitude has been used with Slimani’s women, and Adèle has it.

A raft of reviews chide Slimani for writing a tale that “misses an opportunity” to portray female sexuality in a way the reviewer evidently prefers on political grounds. This is not the book we need at this moment, we’re told. Justified moralism prevails. I agree with many of the values behind these objections. Moralism, though, is moralism, and no better than that.

Adèle joins several grand French traditions. Its clean, affectless prose may recall Camus. (A gifted stylist, Slimani can pack a sneaky wallop when she wants.) Where Camus finds meaning in friendship or the fight against evil, however, there’s no such thing here. The serially sexual heroine recalls, superficially only, figures such as Emmanuelle and O. But where they are at least sometimes emotionally invested in their intimate lives, the sex here means nothing before or after. Bored stiff, alienated, Adèle is a poster woman for ennui and anomie. Her husband rightly says: “You know, you’re just as ordinary as we are, Adèle.” Yet in other literary hands, bored and alienated ordinary people are more interesting.

Which leaves her, and us, in world where everyone is hateful. And it’s a huis clos. Adèle is headed for either a very bad end or a kind of well-meaning domestic internment in her new home in the country, which she despises as much as she despises Paris.

The best I can say? Adèle is a skillfully turned novel that gives us nothing we expect. Clearly, this is intentional, and clearly, this is brave. It may be an interesting interrogation of those expectations. It’s not a fun read, though, or a world I want to be in. It is a tale of misery. It may tell us most of all about ourselves and the limits of our tolerance.