‘Archive of Alternate Endings’ by Lindsey Drager: The world as a story told different ways

It may seem intricate, out of sequence, and twisty-turny, but this finely-turned little novel harbors an original idea: that multiplicity is a sign not of fragmentation but rather of stories with alternate endings.

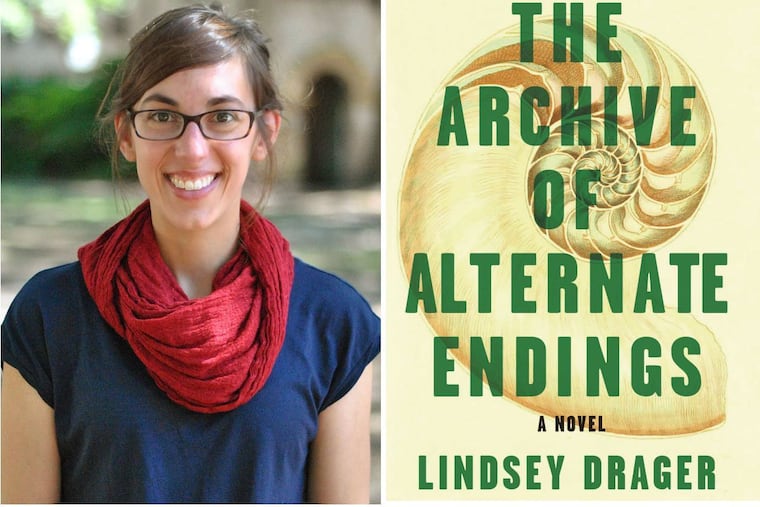

The Archive of Alternate Endings

By Lindsey Drager

Dzanc Books 160 pp. $16.95

Reviewed by R. P. Finch

The Archive of Alternate Endings by Lindsey Drager epitomizes the so-called small press novel: It is wildly creative, challenging yet readable, and may not be pointed toward a broad mainstream audience. Many such novels run the risk of being overlooked — which, in this case, would be more than regrettable.

For all but three years between 1378 and 2365 in which there is a flyby of Halley’s Comet, Drager provides a narrative with characters viewing (or awaiting) its arrival, together with a motif related, in one way or another, to Hansel and Gretel. Navigation is a recurring theme, and, to guide the reader through this intricate (and possibly for some readers too non-linear) tale, at the top of each chapter is a helpful list of which years will be touched on.

Among the novel’s themes is that of recurrence, in both form and content. Chapters are composed of either full sections of text or mere snippets, all ricocheting in time among the years in question, echoing the recurrent themes and the cyclical patterns in nature. References to any given year also recur in multiple chapters.

As for recurrent content, we have pairs of siblings; physical objects lost and found and lost again (a fossilized nautilus shell, a reappearing cookie jar containing, variously, gingerbread, the original drawings for The Illustrated Hansel and Gretel, and human cremains); and orbits and curves in nature, including the curvature of space itself, where (as with stories) an ending may also be seen as a beginning.

As for themes, we have folktales and their telling. Questions arise. What is the essence of a story, of narration and illustration? What is the effect of choosing one particular version of, say, Hansel and Gretel? Different versions have alternative endings, some much darker than the one honed and polished by the Brothers Grimm. In one, the son is cast out because he is gay, and his sister leaves home to help her sibling survive in the woods.

Related are themes of The Witch and especially The Woods, on which Drager concentrates her narrative focus. As she puts it: “The stories are about power and despair. There are riddles and traps. There are monsters and ghosts and broken bodies. … [N]early all the characters enter, exit or find themselves lost in the woods. … The forest … is where children go to grow up.”

Among the twins and other paired sibs are Hansel and Gretel in 1378, their intricate relationship, their mutual protection, devotion, and benign deception; Gutenberg and his twin sister (with her own harrowing secret tale) in 1456; and a gay computer programmer and his caretaker sister at the height of the AIDS epidemic in 1986.

Yet another theme is transmission of information. This starts from the oral telling of regional folktales and proceeds to the writing down of chosen versions, followed by analog replication by means of Gutenberg’s printing press, followed by infinite virtual replication via the programmer’s digital invention, called the Universal Forest by him and called the World Wide Web by all of us. In 2211, twin space probes transmit Hansel and Gretel in binary code into the depths of space in the hope that a sibling planet of Earth might capture the signals.

Drager is, of course, not the only author to engage in modern or post-modern contextualizing of folktales. But she has an original idea: that multiplicity is a sign not of fragmentation but rather of stories with alternative endings.

Parents induct children into humankind by instilling in their young brains and hearts the folktales of our human race, mediated by our various cultures but reflecting universal fears along with the morals of the stories, which teach us how to navigate our own way in the world.

Although relatively slim, Drager’s novel is a vast and convoluted treasure trove. She does a fine job of illuminating the darker concepts and human relationships with her rich, confident, and sometimes startling writing. Reading The Archive of Alternate Endings is an enriching literary experience the reader will remember hauntingly ever after.

R. P. Finch is author of “Skin in the Game” (Livingston Press).