‘Lives of Houses’ is a lovely book to savor while you’re stuck at home | Book review

Wide-ranging essays explore the residences of "writers, politicians, composers, collectors, artists ... men and women who have shaped and recorded the history of their houses through their own work.”

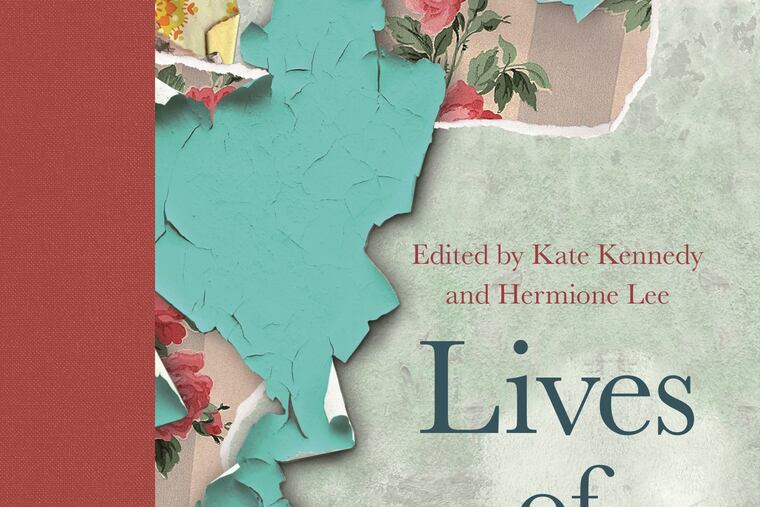

Lives of Houses

Edited by Kate Kennedy and Hermione Lee

Princeton. 304 pp. $24.95

Reviewed by Michael Dirda

For much of the country, sheltering in place has been a wearisome but essential civic duty. We don’t want to get sick ourselves, and we don’t want to bring any sickness to others. So we stay home. It’s the right thing to do.

Having done heaps and heaps of living in Casa Dirda recently, how could I resist Lives of Houses? A recently published collection of essays edited by the biographers Kate Kennedy and Hermione Lee, the wide-ranging volume investigates the residences of "writers, politicians, composers, collectors, artists ... men and women who have shaped and recorded the history of their houses through their own work.”

The book’s contributors include novelist Julian Barnes writing about the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius’ home, Ainola; historian David Cannadine on Chartwell, where Winston Churchill lived; Yeats biographer Roy Foster describing the poet’s richly symbolic but clammy and inhospitable tower retreat Thoor Ballylee; and Jenny Uglow on Edward Lear’s Villa Emily in San Remo.

A few of the best essays, however, aren't about famous people. Margaret MacMillan — former warden of St. Antony's College, Oxford — re-creates the warmth and security of her Toronto childhood in "My Mother's House":

“In the winters (was there always snow and ice in those days?) we came into the kitchen in skates, just off the rink that our neighbour across the back fence made every year. She never minded. We argued, talked about the day, and watched for the warning signs that my two youngest brothers were about to fight as each slipped lower in his chair better to be able to kick the other.”

In another fine piece, novelist Alexander Masters learns how people become “unhoused” by talking with the homeless at the Matthew 25 Mission. (Mathew 25 contains the verse, “Whatever you did for the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.”) Elleke Boehmer, professor of world literature in English at Oxford, addresses the trauma of cultural and personal displacement through the example of African writer Dambudzo Marechera, whose short story collection, The House of Hunger, won the 1979 Guardian First Fiction Prize. Marechera wrote much of the book while living in a tent in a meadow near Oxford, from which he had been expelled for violent and asocial behavior.

An expert on Benjamin Britten, Lucy Walker notes that this world-famous composer viewed himself as a regionalist, intending his music primarily for the people of his hometown of Aldeburgh. Laura Marcus — Goldsmith’s Professor of English at Oxford — reminds us that H.G. Wells’ mother worked as a housekeeper at Uppark, where underground service tunnels connected the kitchens and the main house. Years later, when her son came to write The Time Machine, his Morlocks dwell in subterranean darkness and feed on the effete Eloi of the surface world.

Virginia Woolf, notes Hermione Lee, once compared a woman’s nature to “a great house full of rooms,” where most people only see the public reception areas, while “in the innermost room, the soul sits alone and waits for a footstep that never comes.” Many footsteps, though, have trod the winding stairs and passageways of Sir John Soanes’s London home, which the neoclassical architect stuffed with paintings, sculpture, and every kind of bric-a-brac. In tracing the private museum’s 200-year history, Soanes’ biographer Gillian Darley quotes from its current deputy director, Helen Dorey, who happens to be a friend of mine. At that moment this imposing and labyrinthine mansion suddenly seemed almost homey.

To introduce the sorrowful life of World War I poet and composer Ivor Gurney, Kate Kennedy writes, "There are websites, if you know where to look, full of images compiled by anonymous people with a passion for breaking into derelict asylums and taking photographs, the creepier the better." Gurney was certified insane in 1922 and passed the rest of his life in mental hospitals, dying in 1937. Deeply attached to his native Gloucestershire, he never saw its countryside again except as familiar, heartbreaking place-names on an Ordinance Survey map.

Two of my favorite essays, by Seamus Perry and Sandra Mayer respectively, offer guided tours of W.H. Auden’s apartment at 77 St. Mark’s Place in New York, where the poet lived between 1954 and 1972, and his late-in-life Kirchstetten house in Austria. Auden famously united minimum attention to his living conditions with maximum regard for routine and order. He wore the same suit day after day, padded around Manhattan in carpet slippers, and utilized his kitchen sink as a toilet. Composer Igor Stravinsky called him “the dirtiest man I have ever liked.” Relying on literary journalism to pay his bills, Auden toiled at his desk every day from 9 a.m. till 4 or 5 p.m., then enjoyed a massive cocktail or two, sat down to a well-prepared dinner promptly at 6, and toddled off to bed as early as 9:00, sometimes shooing guests out the door. In Austria, the poet acquired a yellow Volkswagen, eventually used as the getaway car in a series of robberies committed by a longtime lover.

From the Washington Post.