‘How Do We Look’ by Mary Beard: A refreshing tour of world art, touching God and humanity

This vigorous, witty book, based on the author's part in the "Civilisations" series, looks at how we look at art, and how art approaches both the human body and the divine. It ends with a surprising definition of civilization itself.

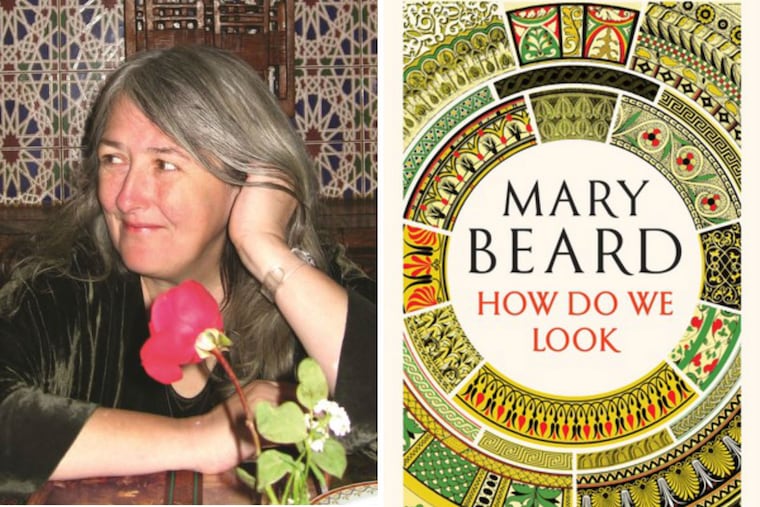

How Do We Look

The Body, the Divine, and the Question of Civilisation

By Mary Beard

Liveright. 240 pp. $24.95

Reviewed by John Timpane

If ever I needed a guide to teach me how to look at art — or, better, how to consider the way art is looked at, and how it responds to that gaze — I’d choose Mary Beard. She writes spacious, accessible English without sacrificing depth or value. She invites you in, and when you’re done, you feel smarter because she has taught you well.

This book derives from Beard’s work in the 10-part BBC Civilisations series that aired this year on PBS. In it, Beard romped round the world with Simon Schama and David Olusoga. Built on Kenneth Clark’s landmark 1969 show Civilisation, the new series widened the aperture, more global, diverse, multicultural (not just Western): Note the plural in the newer series’ title. In the mode of even the grandest TV, the book is somewhat breezy, yet it treads profound pathways.

How Do We Look is a witty title, something you say when, all dressed up, you’re taking a turn in front of the viewer for his or her evaluation. Beard’s point is that art is forever doing just that. Renowned art historian Ernst Gombrich says there’s no such thing as art, only artists. No, says Beard: There’s art, all right, and not just in the beholder’s eye. Often, art solicits that eye and teaches it how to look.

A simple idea, even unfashionable in some quarters. It helps us recover, though, the two-way conversation between art and the beholder. What a tour Beard gives us, from Mexico to Egypt, Cambodia to Turkey. The book is divided into two parts: “The Body in Question,” addressing how art has approached the human body; and “The Eye of Faith,” addressing art’s exalted, conflicted approaches to the divine.

The chapter “Greek Bodies” shows us ancient pots painted with images of good wives and drunkards, teaching the viewer what it means to be Greek. In the superb chapter “The Look of Loss: From Greece to Rome,” Beard considers the spectacular, fairly recently discovered statue of Phrasikleia (about 550 B.C.) and the stunningly realistic portraits on the coffins of some Roman-era mummies (such as you can see at the Penn Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology). She realizes these “were attempts to keep the dead present among the living and to blur the boundary between this world and the next.”

In “The Greek Revolution,” Beard tackles the innovative, explosive “Greek Revolution,” a lifelike approach to sculpture in the ancient Greek-speaking world that has determined the course of most Western sculpture. It was an artistic bid to make sculpture live, to bring life into art and vice versa. Both the gains and losses were immense and permanent.

In the second half, Beard appreciates the mutual fertilization of art and religion, giving us, as she writes, “some of the most majestic and affecting visual images ever made.” She begins with Angkor Wat, one of the biggest religious artworks anywhere, which, she writes, was intended to body forth the claims of Hinduism and “bring the natural, divine, and human worlds into harmony.” In this enormous, ineffable temple complex, even the sun is part of the drama.

Islamic art, down to the great tradition of calligraphy, is invested with religious meaning. The network of monasteries and prayer halls in Ajanta, India, leads us into darkness to grapple with gods all around us. The Church of San Vitale at Ravenna (built 540), among the oldest of all Christian churches, portrays Jesus as young man, and as symbolic Lamb of God, and as an older man barely distinguishable from God the Father. We are being taught to see the divi;nity of Christ in all its dimensions.

“A lot depends on who’s looking,” Beard writes. That’s why we need a guide now, when the audiences for these artworks are but traces of history. Someone like Beard can rebuild the original gaze, teach us to see as these artists and audiences did.

Beard’s closing point concerns civilization itself. Our very belief in civilization, however we define it, is what pulls civilization together, whether in China or in Italy, Ely Cathedral or the Parthenon. “So if you ask me what is civilisation,” she writes, “I say it’s little more than an act of faith.”