The writer who inspired Sue Grafton — her father — is republished in a 1943 mystery novel | Book review

The Library of Congress thinks it's time for a C.W. Grafton reconsideration as it revives his novel, "The Rat Began to Gnaw the Rope."

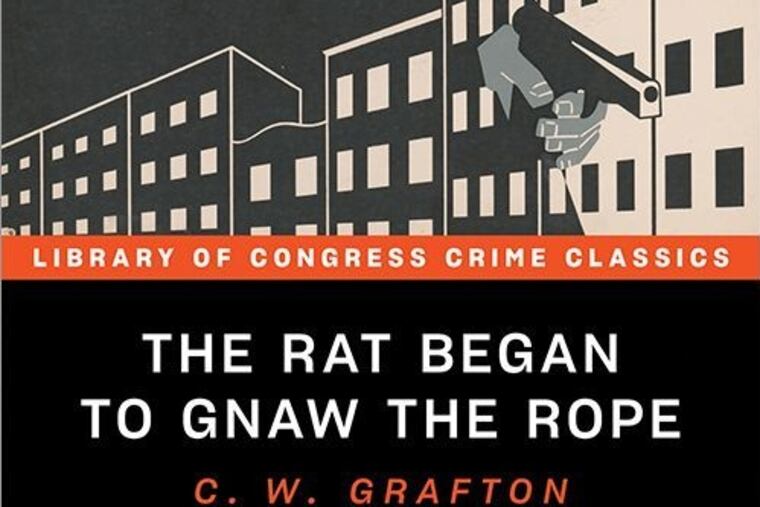

The Rat Began to Gnaw the Rope

By C.W. Grafton

Library of Congress Crime Classics in partnership with

Poisoned Pen Press and Source Books. 304pp. Paperback, $14.99

Reviewed by Maureen Corrigan

Sue Grafton published ‘A’ Is for Alibi, the first novel in her beloved, best-selling Kinsey Millhone series in 1982 (the year her father died). C.W. Grafton was an avid mystery reader and he encouraged his daughter in her love — and eventual mastery — of the form. The elder Grafton wrote three suspense novels himself, but only the legal thriller, Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1951), is remembered (if at all) today.

The Library of Congress thinks it's time for a C.W. Grafton reconsideration.

The library has recently partnered with Poisoned Pen Press to reprint underappreciated American mysteries in a series called Library of Congress Crime Classics.

C.W. Grafton’s 1943 mystery The Rat Began to Gnaw the Rope is not simply a historical curio, but a genuinely offbeat and entertaining suspense story.

The accidental hero and narrator of this tale is Gilmore "Gil" Henry, a self-described "short," "pudgy" lawyer who is the youngest partner in a small-town firm. The novel opens on a scene that was already formulaic by the time Sherlock Holmes began receiving clients at 221B Baker Street: Gil's secretary alerts him that a distraught young woman is outside his office, requesting to see him. In walks Miss Ruth McClure, bearing a curious tale: Ruth's father, who's recently died in an accident, was a foreman for the Harper Products Company in nearby Harpersville. Before his death, Ruth's father instructed her to "hold tight" to the stock he owned in the company. Now, the owner, Mr. William Jasper Harper, has offered to buy that stock for more than the market value. Ruth is a smart cookie and senses something is rotten. She asks Gil to drive to Harpersville and suss out what's happening. Here's Gil, a mere third of the way through the novel, summing up his ensuing adventures to Ruth:

"I went from [Harpersville] to Louisville and stole some records trying to figure out your puzzle for you and before I got through, I felt as if the whole town was alive with policemen peering at me from behind telephone poles and from under automobiles. I flew back to my office and got knocked cold in the hall and somebody searched my room at the YMCA. I nearly got arrested for attempted blackmail … and I've quit my law firm. I am rewarded by the undying love and affection of everyone concerned — I don't think."

The warp-speed pace of Grafton’s plot is intensified by its short chapters, most averaging three pages. It’s the tone, however, that really distinguishes this novel. The introduction by Leslie S. Klinger makes the claim that Grafton was one of the first American crime novelists to infuse his story with humor — not simply the wisecracks muttered by hard-boiled detectives like Sam Spade and Phillip Marlowe, but an all-encompassing comic viewpoint. For instance, while he’s getting conked on the head and stumbling over corpses, Gil is doing screwball things like grabbing nearby dames and kissing them. (Enlightened these suspense tales of yore are not. This one contains racist, classist, ageist, and sexist comments.) When Ruth breaks into tears after her brother has been arrested, Gil gives a funny spin to the classic tough guy “suck-it-up” speech:

“Listen little Bopeep, the sheep you are losing aren’t the kind that come home wagging their tails behind them. You have to go out and look for them. ... Now get up and wash your face and powder your beak and let’s start something.

“It didn’t go over too big. The look she gave me made it plain that in her bluebook the value of a ’41 model Gilmore Henry was lower than net income after taxes.”

The merrily macabre tone of Grafton’s novel makes up for thin characters and many an implausible plot turn. No matter. How can you resist a novel filled with lingo like “powder your beak?”

Corrigan, who is the book critic for the NPR program “Fresh Air,” teaches literature at Georgetown University. She wrote this review for the Washington Post.