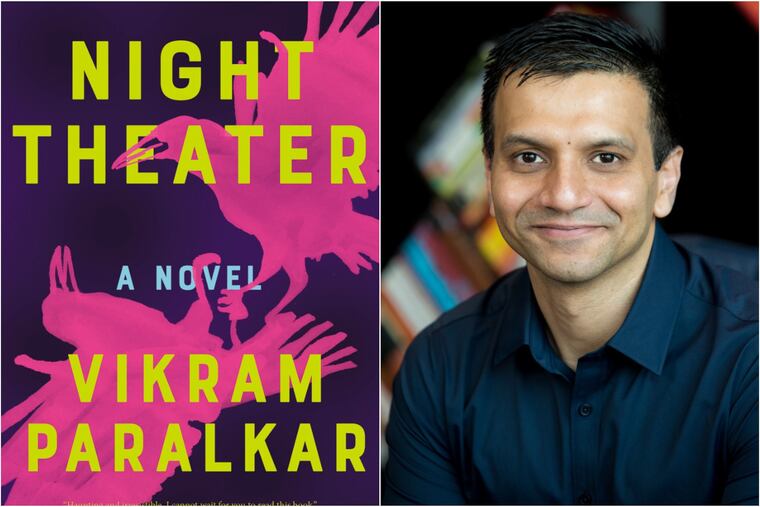

In this Penn doctor’s novel ‘Night Theater,’ a surgeon is asked to bring a slain family back to life

Medicine meets magical realism in "Night Theater," a novel by Dr. Vikram Paralkar, an oncologist and researcher at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Time Magazine called it "one of the 12 new books you should read in January."

The idea, said Vikram Paralkar, came to him “in a flash.” A surgeon would be faced with bringing the dead back to life over the course of one night.

In the story, set in a small clinic in rural India, the surgeon is confronted by a man, his heavily pregnant wife, and their young son, with the request that he operate on the family to repair wounds sustained in a murderous attack. Though they’re walking and talking, their blood isn’t flowing. They are dead, and will remain so, he’s told, unless he can repair their bodies by morning.

Medicine meets magical realism in Night Theater (Catapult, $16.95), a novel that Paralkar, an oncologist and researcher at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, wrote during his training. The story, he said, crystallized questions he’d been considering about how medicine is practiced by flawed humans, about God and religion, and about the routine corruption he’d witnessed in his native India.

It was first published in India in late 2017 as The Wounds of the Dead — a reviewer for the Indian newspaper the Hindu called it “perceptive and absurdly humorous in ways I hadn’t expected” — and made its U.S. debut this month. Hailed by Time magazine as “one of the 12 new books you should read in January,” it’s Paralkar’s second work of fiction, following 2014′s The Afflictions, a compendium of imaginary diseases that grew out of an idea he’d had for a short story. He’s at work on a third.

We asked Paralkar about balancing medicine and writing, about growing up in Mumbai above his family’s hospital, and about his own views on the afterlife. This interview has been edited and condensed.

What’s it like to finally have this book come out in the country in which you live and work?

It feels wonderful, actually, because several of my colleagues and friends had been asking about the book for a long time. And we had a wonderful launch at the Mütter Museum. It was great to have all of the different circles of people with whom I interact in Philadelphia be at the launch.

I understand you grew up in a medical household, living in the same building where your parents worked. What was that like?

My father’s a surgeon, my mother is a gynecologist. Both of them are retired. So in India, there still exists the kind of setup that no longer exists in the United States, which is that doctors start their own small hospitals, which would have consultation rooms and [an] operating room and several rooms where there would be beds and they would admit patients, perform surgeries, and care for them. And they’d be family-run, small boutique kind of hospitals. And my parents started one such hospital about 40 years ago, and it began as a small three-room hospital and then expanded to a fairly large facility on the ground floor and we lived on the floor above it.

It was a daily experience for me to wander around the hospital and say hello to patients. And actually, my dad would take me into the operating room from time to time and show me surgeries. As a result, ever since I was 8, human anatomy and the fact that surgeries have to be performed from time to time to preserve health, is something that was very normal to me.

Was becoming a writer something you ever considered growing up?

No one in my family or my immediate surroundings is a writer. But my father and my mother both loved reading. I did not always have access to every toy that I wanted, but access to every book that I wanted, and now, looking back, I realize what a good parenting decision that was.

We would go to book fairs. My most fond memories as a child are of going to these book fairs, and we would just wander around, and at the end of the day I would go home with two bags full of books that were so heavy that I could barely even lift them. So I was a pretty voracious reader as a child and as a teenager, and then I became introduced to literature, to Jorge Luis Borges and to Gabriel García Márquez and Salman Rushdie, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, around the age of 18.

I have continued to be an avid reader and have always felt that when the time was right for me to say something worth saying that I would want to get it published.

Being a doctor and a researcher has to be demanding. When do you find time to write?

I’m not sure that I do [laughs]. I try to squeeze it in as and when I can. Having short windows isn’t exactly conducive to writing. It would be great if I had the luxury to go to an artists’ retreat for six weeks and lock myself in a house in the woods and hammer out a manuscript, but that’s just not an option that’s available to me because of my career. I consider writing to be an important part of my life. It’s more than a hobby.

Do your patients know you’re a writer?

I try not to bring up my writing in my interactions with patients, but, yes, sometimes they know I’m a writer. I mean, we Google everyone these days.

I had this somewhat strange experience with a young woman who had just been diagnosed with leukemia. And the leukemia was curable, but it would require an intense course of treatment, and I had had a very detailed discussion with her about what we would do. And at the end of it, she began to ask me about my writing. And I was happy to talk to her about it, but it felt like a very strange transition to go from talking about her life, her prognosis, to something that purely concerned me and my life.

Would it be spoiling too much to say “Night Theater” takes a somewhat dim view of the afterlife?

I think that would be fine. The idea of the afterlife is in many ways a source of consolation, but also deeply problematic. It stems from, of course, human beings’ fear of the finite, that at some point we will cease to exist. So let’s solve that problem by stating that we will exist forever. And forever is a long time. And what kind of existence would you want that would make such a prolonged existence even worth it?

I, personally, am more sympathetic to the kind of view that the Greek philosopher Epicurus had, which is that you should think of life as a feast, where you at some point will step away from the table of existence, but you do so having satisfied yourself in having fed well on this life.

So what you’re saying is you don’t personally have a belief in an afterlife?

No, I don’t personally have a belief in the afterlife, but I do understand why people yearn for it.

What are you reading these days?

Well, most of the reading that I end up doing these days is scientific articles. But I really am trying to catch up with several books that I’ve heard so much about. One is by Valeria Luiselli, Lost Children Archive. Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. And the third book I’m looking forward to reading is called The Faculty of Dreams by Sara Stridsberg.

One of the pleasures and misfortunes of loving literature is that you constantly have books to read, and you constantly have the awareness that you will never, ever finish reading the books that you need to.

Vikram Paralkar will read from “Night Theater” at 6:30 p.m. Feb. 27 at Penn Book Center, 130 S. 34th St.