Albert C. Barnes loved Henri Rousseau’s ‘honesty of approach.’ So he built one of the world’s largest Rousseau collections.

At an ongoing show, 11 of Barnes' 18 Rousseaus are on display, along with some loaned from MoMA and Paris' Musée d’Orsay.

Lions, and tigers, and bare women.

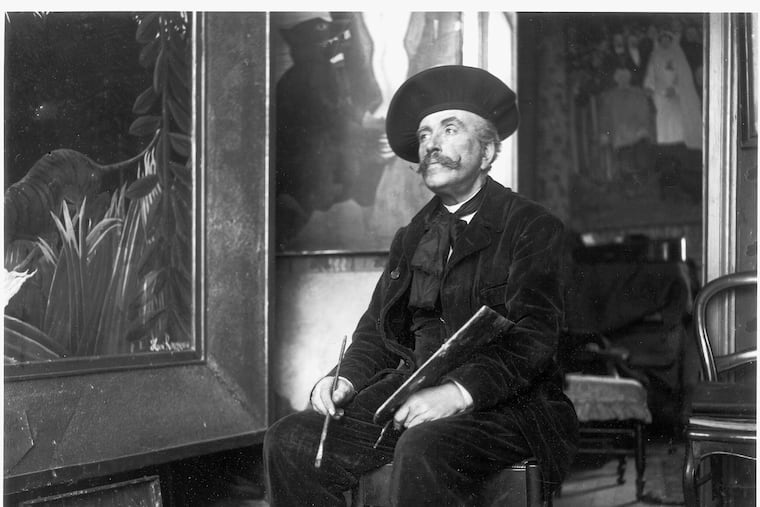

These are some of the figures in the iconic jungle pictures by Henri Rousseau (1844-1910), a self-taught French artist who strove to realize financial and critical success as a professional painter.

He also had a criminal record of embezzlement and bank fraud.

Despite a lack of formal art training, Rousseau was confident he was a significant artist who deserved official recognition. Nicknamed “Le Douanier” (the customs officer) by Alfred Jarry, a playwright who was also a family friend, Rousseau did collect tariffs on goods coming into Paris.

In 1893 at age 49, he retired early with a modest pension to devote himself to full-time painting.

Whether portraits, landscapes, or the uniquely imagined jungle scenes, Rousseau’s pictures reveal features common to an artist with no academic art instruction: anatomical inaccuracies, flatness, scale distortion, outlined forms, and repetitive patterning. Some of his canvases defy logic, mixing fact and fantasy like Tropical Landscape — An American Indian Struggling with a Gorilla (1910).

At the Barnes’ ongoing “Henri Rousseau: A Painter’s Secrets,” Rosseau’s art is arranged in seven thematic sections.

The curators — Nancy Ireson, the deputy director of collections and chief curator at the Barnes, and Christopher Green, professor emeritus at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London — have assembled 56 works including major loans from museums around Paris, to showcase an artist with “entrepreneurial energy in marketing,” as Green put it in a recent press preview.

The compact exhibition offers a glimpse at Rousseau’s journey from an outsider artist to a modern master, revealing, as the exhibition notes say, “the thoughts and intentionality behind some of his most famous works.”

Interestingly, an ongoing show at the Philadelphia Art Museum is titled “Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100.” Rousseau’s visionary work was admired by Andre Breton, who wrote the Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924. Although Rousseau deals with such similar matters as childlike imagination, eroticism, and dreamy scenarios, no recognition of his role as an inspirational precursor is presented in this survey of about 180 artworks up the Parkway.

Yet, Le Douanier was certainly on that road to surrealism.

Between 1923 and 1929, Albert C. Barnes, the voracious collector of modern art, acquired 18 paintings to form the world’s largest group of Rousseau canvases under one roof. (Eleven are displayed in this show, nine of which will travel overseas for the first time in 40 years when the show goes to the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris next year.) Barnes admired Rousseau’s “honesty” of approach, saying, in 1925, “his pictures have the charm of a child’s fairy-tale.”

“But there is nothing childish or untutored in the skill with which they are executed,” he maintained.

Rousseau did not begin painting until he was in his 40s. He submitted work to the recently established Salon des Indépendents, the nonjuried annuals that required only a modest fee and provided a venue to anybody to have work on public display.

The 1894 painting The War, an allegorical image, raised his profile and elicited enthusiastic as well as derisive responses. The central figure is strangely positioned not on but in front of the galloping horse as it leaps across a battlefield strewn with bodies and scavenging black crows.

A decade later, Scouts Attacked by a Tiger (1904), a large jungle picture of impending danger, attracted considerable notice. Rousseau’s rather novel tropical scenes like this one began to gain some notoriety among a circle of talented bohemian personalities that included Pablo Picasso.

Louis Vauxcelles, the young art critic who coined the terms fauvism and cubism, acknowledged that Rousseau was becoming “a celebrity in his own way.”

The artist, however, never left France.

His jungle paintings are pure fantastic compositions of faraway places created in his Parisian studio. For visual reference, he used sundry postcards and photographs and made repeated visits to the Jardins des Plantes with its botanical gardens and zoo. Rousseau found his niche painting such “imaginative voyages” during the late years of his career.

When the artist was on trial for participation in a bank fraud scheme in late 1907, his lawyer brought to court a tropical painting depicting monkeys (the exact canvas is not known). Based on the visual evidence of the picture, the defense maintained that Rousseau was too naive to know that he was committing a crime.

It worked. The artist only received a suspended sentence.

The piece de resistance of the Barnes exhibition is the last gallery where three key works by Rousseau have been brought together for the first time: The Sleeping Gypsy (1897), from the Museum of Modern Art in New York; Unpleasant Surprise (1899-1901), in the Barnes collection; and The Snake Charmer (1907), from the Musée d’Orsay, which entered the Louvre in 1936, giving Rousseau the official state recognition he had hoped to realize in life.

With striking light effects and subtle tonalities, these fantasy scenes remain poetic, mysterious, and beguiling. They certainly raise more questions than answers. It is understandable why Green described Rousseau as a “story giver not a storyteller.”

In 1908, Picasso shined a spotlight on Rousseau when he bought The Portrait of a Woman (1895) for a few francs. The formidable portrait depicts a woman (believed to be a Polish lover of Rousseau), who stands in front of a balcony and curiously holds an upside-down branch like a cane. Though it came from a secondhand dealer who was selling the canvas for reuse, Picasso always spoke “movingly about this picture, keeping it with him all his life,” said Green.

That large Rousseau picture is here on loan from the Musée National Picasso-Paris.

To celebrate his newly acquired Rousseau, Picasso organized a dinner party with the painting as the centerpiece in his Montmartre studio. In front of an illustrious circle of Picasso’s avant-garde artist friends as well as Gertrude and Leo Stein, Rousseau toasted with unabashed chutzpah his host: “We are the great painters of our time, you in the Egyptian style, I, in the modern style.”

Guillaume Apollinaire, an influential figure of the Parisian avant-garde who was also invited to that Picasso party, prophetically saluted the guest of honor: “Vive, Vive, Rousseau!”

“Henri Rousseau: A Painter’s Secrets” through Feb. 22, Barnes Foundation, 2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, barnesfoundation.org

“Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100″ through Feb. 16, Philadelphia Art Museum, 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, visitpham.org