How Americans are using AI at work, according to a new Gallup poll

A poll finds that American workers have adopted artificial intelligence into their work lives at a remarkable pace over the past few years.

American workers adopted artificial intelligence into their work lives at a remarkable pace over the past few years, according to a new poll.

Some 12% of employed adults say they use AI daily in their job, according to a Gallup Workforce survey conducted this fall of more than 22,000 U.S. workers.

The survey found roughly one-quarter say they use AI at least frequently, which is defined as at least a few times a week, and nearly half say they use it at least a few times a year. That compares with 21% who were using AI at least occasionally in 2023, when Gallup began asking the question, and points to the impact of the widespread commercial boom that ChatGPT sparked for generative AI tools that can write emails and computer code, summarize long documents, create images, or help answer questions.

Home Depot store associate Gene Walinski is one of the employees embracing AI at work. The 70-year-old turns to an AI assistant on his personal phone roughly every hour on his shift so he can better answer questions about supplies that he is not “100% familiar with” at the store’s electrical department in New Smyrna Beach, Fla.

“I think my job would suffer if I couldn’t because there would be a lot of shrugged shoulders and ‘I don’t know’ and customers don’t want to hear that,” Walinski said.

AI at work for many in technology, finance, education

While frequent AI use is on the rise with many employees, AI adoption remains higher among those working in technology-related fields.

About 6 in 10 technology workers say they use AI frequently, and about 3 in 10 do so daily.

The share of Americans working in the technology sector who say they use AI daily or regularly has grown significantly since 2023, but there are indications that AI adoption could be starting to plateau after an explosive increase between 2024 and 2025.

In finance, another sector with high AI adoption, 28-year-old investment banker Andrea Tanzi said he uses AI tools every day to synthesize documents and data sets that would otherwise take him several hours to review.

Tanzi, who works for Bank of America in New York, said he also makes uses of the bank’s internal AI chatbot, Erica, to help with administrative tasks.

In addition, majorities of those working in professional services, at colleges or universities or in K-12 education, say they use AI at least a few times a year.

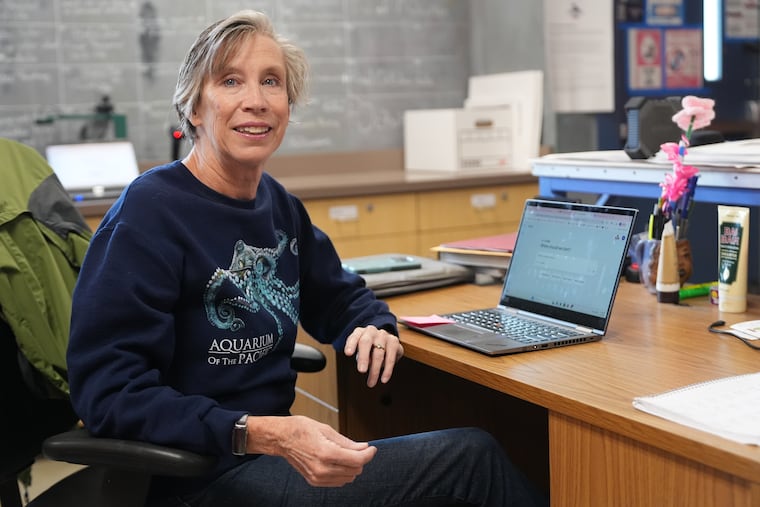

Joyce Hatzidakis, 60, a high school art teacher in Riverside, Calif., started experimenting with AI chatbots to help “clean up” her communications with parents.

“I can scribble out a note and not worry about what I say and then tell it what tone I want,” she said. “And then, when I reread it, if it’s not quite right, I can have it edited again. I’m definitely getting less parent complaints.”

Another Gallup Workforce survey from last year found that about 6 in 10 employees using AI are relying on chatbots or virtual assistance when they turn to AI tools. About 4 in 10 AI users at work reported using AI to consolidate information or data, to generate ideas, or to learn new things.

Hatzidakis started with ChatGPT and then switched to Google’s Gemini when the school district made that its official tool. She has even used it to help with recommendation letters because “there’s only so many ways to say a kid is really creative.”

Benefits and drawbacks of AI adoption

The AI industry and the U.S. government are heavily promoting AI adoption in workplaces and schools. More people and organizations will need to buy these tools in order to justify the huge amounts of investment into building and running energy-hungry AI computing systems. But not all economists agree on how much they will boost productivity or affect employment prospects.

“Most of the workers that are most highly exposed to AI, who are most likely to have it disrupt their workflows, for good or for bad, have these characteristics that make them pretty adaptable,” said Sam Manning, a fellow at the Centre for the Governance of AI and co-author of new papers on AI job effects for the Brookings Institution and the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Workers in those mostly computer-based jobs that involve a lot of AI usage “usually have higher levels of education, wider ranges of skill sets that can be applied to different jobs, and they also have higher savings, which is helpful for weathering an income shock if you lose your job,” Manning said.

On the other hand, Manning’s research has identified some 6.1 million workers in the United States who are both heavily exposed to AI and less equipped to adapt. Many are in administrative and clerical work, about 86% are women, and they are older and concentrated in smaller cities, such as university towns or state capitals, with fewer options to shift careers.

“If their skills are automated, they have less transferable skills to other jobs and they have a lower savings, if any savings,” Manning said. ”An income shock could be much more harmful or difficult to manage.”

Few workers are concerned about AI replacing them

A separate Gallup Workforce survey from 2025 found that even as AI use is increasing, few employees said it was “very” or “somewhat” likely that new technology, automation, robots, or AI will eliminate their job within the next five years. Half said it was “not at all likely,” but that has decreased from about 6 in 10 in 2023.

Not worried about losing his job is the Rev. Michael Bingham, pastor of the Faith Community Methodist Church in Jacksonville, Fla.

A chatbot fed him “gibberish” when he asked about the medieval theologian Anselm of Canterbury, and Bingham said he would never ask a “soulless” machine to help write his sermons, relying instead on “the power of God” to help guide him through ideas.

“You don’t want a machine, you want a human being, to hold your hand if you’re dying,” Bingham said. “And you want to know that your loved one was able to hold the hand of a loving human being who cared for them.”

Reported AI usage is less common in service-based sectors, such as retail, healthcare, or manufacturing.

Home Depot did not ask Walinski to use AI when he got a job at the store last year, after a decades-long career in the car business. But the home improvement giant also did not try to stop him and he is “not at all worried” that AI will replace him.

“The human interface part is really what a store like mine works on,” Walinski said. “It’s all about the people.”