A Cobbs Creek man taped basketball broadcasts for five decades. His grieving family wants to find a home for his life’s work.

From 1986-2024, Billy Gordon recorded thousands of basketball games onto VHS tapes. He died in 2025 and his family wants to pass them on to someone who appreciates them.

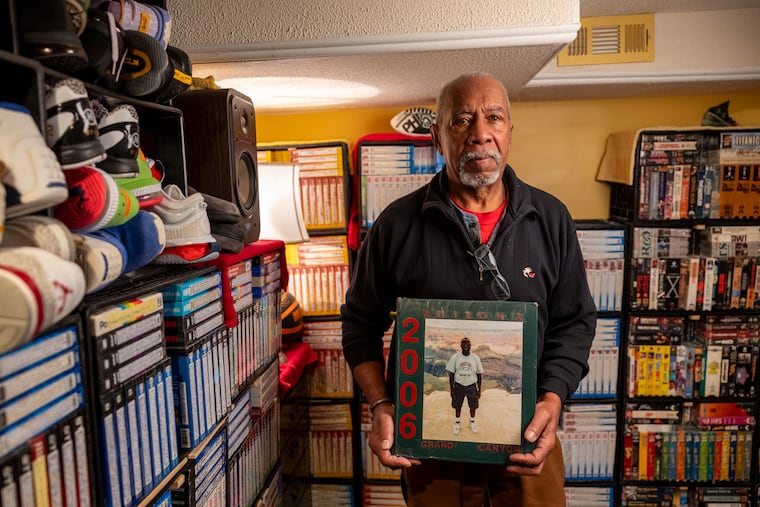

Billy Gordon was surrounded by the tapes. They were the first thing he saw in the morning, and the last thing he saw at night. His bedroom, in the basement of his grandmother’s Cobbs Creek home, was not big; maybe 190 square feet, if that.

But he found enough space for the thousands of basketball games he’d recorded from 1986 to 2024, all on VHS. Each tape came with a neatly written label, noting the name of the event, the teams who played, each team’s record, and the final score.

They were carefully placed into black crates, organized by year, and stacked on top of one another, creating a technicolor tapestry around his bed. It was an unconventional hobby, but Gordon loved it.

His family wasn’t surprised. Gordon, who worked as a baggage handler at Philadelphia International Airport, was a diehard sports fan with an encyclopedic mind. He could remember statistics about any athlete, no matter how obscure.

So, it only made sense that he’d spend his free time collecting archival footage of everything from Super Bowl XXXIII to his alma mater, Cheyney, to Pepperdine vs. Loyola Marymount in 1987.

“He didn’t miss very much,” said Gordon’s uncle, Ron Hall.

Hall and Gordon lived together in Cobbs Creek for about 15 years. Neither had a traditional work schedule. Hall was a union carpenter who traveled for jobs; Gordon picked up night shifts at the airport.

But in the moments they did overlap, they’d watch games, often with pizza and chicken wings. This tradition continued through the winter of 2024, when Gordon was diagnosed with an autoimmune disease. The illness quickly worsened, and he was moved to a nursing home in King of Prussia.

As he lay in his hospital bed, hooked to a respirator, Hall sat beside him. They cheered on whatever local team was playing that day: the Eagles, Phillies, or 76ers.

“Just to let him know that people love him,” his uncle said.

Gordon died earlier this year, in May, at age 66. He was buried in his blue-and-white Cheyney track suit. To Hall, it was like a losing a brother. It took him months to even step into that basement bedroom.

Once he did, he was stunned. He always knew that his nephew had a VHS collection, but didn’t realize the full extent of it until then.

“The magnitude of what was here really hit me,” he said. “I was in disbelief that he had accumulated so much. That he had taken the time to collect so many things.”

‘A love for the game’

Gordon was born and raised in a sports-loving household. His grandmother, Vernese, was an avid Phillies fan. Hall was too, and would bring his nephew to different ballparks.

After graduating from John Bartram High School in the 1970s, Gordon went on to Cheyney, where he studied industrial arts. It was there that his love for sports information really blossomed.

The young college student had the fortune of overlapping with John Chaney, who was coaching Cheyney’s men’s basketball team.

The Wolves were nothing short of dominant. Chaney led them to a 225-59 record from 1972 to 1982, with eight tournament appearances and one NCAA Division II championship.

Gordon was not athletically inclined, certainly not enough to play on Chaney’s team. But he liked to hang out around the gym and developed a rapport with the players and coaches.

He also showed an attention to detail to which Chaney gravitated.

“He had such a love for the game, and knew the game so well, that he could point something out to this player, that player,” Hall said. “[He] really was just being an asset to the coaching staff.”

Chaney invited Gordon to work at his summer camp, which he ran with Sonny Hill throughout the Philadelphia area. The zealous sports fan couldn’t believe his luck. He’d help with drills, but he also took pride in the little things: packing lunches, inflating basketballs, and setting up exercise equipment.

On rainy days, when the kids couldn’t play outside, Gordon would pop one of his tapes into the VCR.

“Old Temple games,” said his friend, Mia Harris. “Just so the kids could learn.”

She said that Gordon worked with Chaney and Hill from the mid-1980s to the early 2000s. The camp was the highlight of his summer; an opportunity to get to know the legends of the Philadelphia basketball scene.

“They made him feel like a part of the team, even though he wasn’t a player,” Harris said. “He even wore a whistle. That tickled me.”

It was around this time that Gordon started building his VHS collection. He began taping bigger events — the 1987 Stanley Cup Finals, Super Bowl XXII — but basketball was always the bedrock.

He captured the dominance of Michael Jordan, the fearlessness of Kobe Bryant, and every March Madness Cinderella story since the mid-1980s. He chronicled the NBA Finals, the WNBA Finals, and a slew of conference college basketball games.

The sheer number of tapes and labels was dizzying (Hall estimated that his nephew had 40 crates). But upon closer inspection, a trend emerged.

Chaney was hired as head coach of Temple in 1982, a job he kept until 2006. Among the stacks were pockets of his time there: Mark Macon’s first game for the Owls in 1987; the team’s first loss of that historic season, to UNLV, on Jan. 24, 1988.

Gordon recorded years of Temple vs. Illinois, Temple vs. Duquesne, Temple vs. Penn State. There even was a sit-down interview with Chaney, from the late 1980s.

These tapes stuck out. Gordon didn’t personally know any of the NBA greats he filmed. He didn’t know the WNBA stars, either. But he did know John Chaney, long before he became a national figure. And he never forgot him.

Finding a new home

A few months after Gordon died, Hall began to sort through his nephew’s things. It was an emotionally taxing process.

The retired carpenter donated Gordon’s winter coats and appliances to a local men’s shelter in Southwest Philadelphia. He gave his summer gear to a nonprofit that sends gently used clothing to Liberia.

Gordon’s sneaker collection went to Hall’s son, Gamal Jones, and his food was delivered to charity.

The only thing left was the thousand-tape-elephant-in-the-room. Jones looked at his father.

“What do you want to do?” he asked.

“I have no idea,” Hall responded.

Jones listed Gordon’s tape collection on Facebook Marketplace, for the modest sum of $123. The response exceeded the family’s expectations.

They received almost a dozen messages, from NBA superfans, collectors, and archivists. Some offered to travel to Cobbs Creek to assess the collection in person.

Hall recognizes that his nephew’s trove is worth more than $123. But he says this isn’t about the money.

He wants to find a buyer who will share the same passion that Billy Gordon had for 38 years. Someone who will honor his hobby and preserve it.

“He probably would want it to go to somebody that was as enthusiastic about it as he was,” Hall said. “That could really appreciate the time, the energy, that he put in to collect all these.”