Sonny Jurgensen’s colorful off-field reputation was formed in Philadelphia. It was a window into the more human side of our stars.

Jurgensen, a fourth-round draft pick of the Eagles in 1957, played the first seven seasons of his Hall of Fame career with the Eagles. He died last week at age 91.

Sonny Jurgensen was an Eagle and a Redskin but never a saint.

It’s been about a week since the hedonistic Hall of Famer died at 91 and nearly 62 years since he departed Philadelphia for Washington in a trade that left the city’s bartenders as downcast as its football fans.

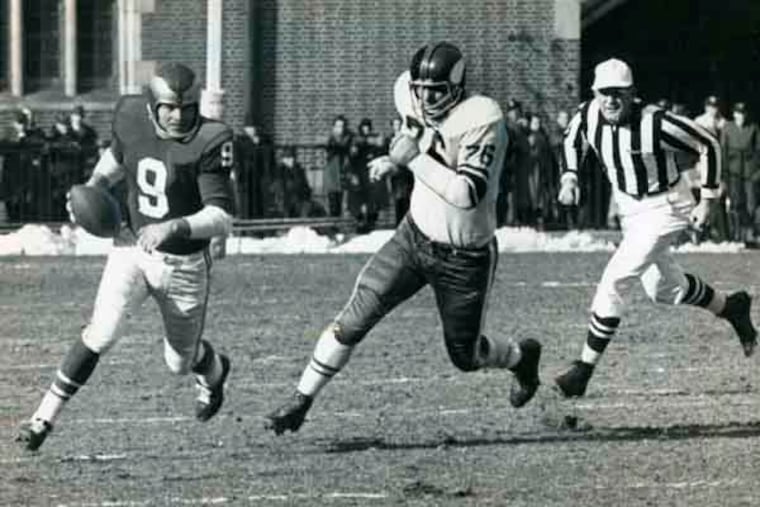

Thinking of Jurgensen now, I still conjure images of that flimsy helmet he wore with its single-bar face mask. I see him squirming in the pocket, quickly surveying the downfield action, then flicking those effortless passes to Tommy McDonald or Pete Retzlaff.

But I also still see, maybe more than in any other athlete from that era, his personal foibles. There was the booze, the pot belly, the mischievous smile, the postgame cigars that jutted from his mouth like middle fingers to those who disapproved.

Jurgensen was one of the first Philly athletes whose lifestyle was as well-known as his talents. Throughout his seven seasons as an Eagle, the last three as a starter, Philadelphia was rife with whispered stories about the redhead’s off-field encounters. It hardly was a secret that he loved liquor, ladies, and last calls.

Like many of his early-1960s Eagles teammates, the native North Carolinian lived during the season at the Walnut Park Plaza hotel at 63rd and Walnut, just a short stagger from one of the team’s favorite bars, Donoghue’s. Jurgensen regularly showed up there as well as Center City spots like the Latimer Club and Jimmy’s Milan.

Another of his favorite haunts was Martini’s, an Italian restaurant and bar in Berwyn where he befriended the owner, Louie DiMartini. DiMartini’s son, Bill, remembered all the nights that his dad and “Uncle Sonny” showed up at their house.

“One night, my siblings and I were in bed when we were awakened by loud singing,” DiMartini said. “Sonny and my dad had just made up a song called ‘Pine Tree.’ The song had no other lyrics but ‘pine tree,’ and they went on singing it for hours.

“Another time, the Eagles couldn’t find Sonny; he hadn’t shown up for practice. We woke up to get ready for school, and as my older brothers went downstairs they found Sonny sleeping on the couch. My father told us, ‘You didn’t see anything.’”

I was a 12-year-old sports nut when I learned of Jurgensen’s off-field proclivities. For me, pardon the expression, it was a sobering experience, perhaps the first time I realized sports heroes weren’t gods.

If my memory is accurate, it happened on a morning in January 1962. The night before, my father, the sports editor of two Philadelphia neighborhood weeklies, had attended his first Philadelphia Sports Writers Association banquet.

I couldn’t wait to hear about it. So at 7:30 the next morning, when he got home from his full-time job as a Bulletin proofreader, I was waiting at the door. As I peppered him with questions, he handed me the event’s program. On its front page were the autographs he’d gathered from sports celebrities he’d encountered there — Gene Mauch, Sonny Liston, Mickey Mantle.

Clearly a little starstruck himself, he eagerly described Mantle’s Oklahoma drawl, Liston’s enormous hands, Mauch’s steely eyes.

Then I saw another signature, this one from Jurgensen, the spirited quarterback who’d just emerged as an NFL star after throwing a league-best 32 touchdown passes during the Eagles’ 10-4 season in 1961.

I awaited my father’s impressions. A virtual teetotaler, his tone shifted when he said, clearly disapproving, “I’ve never seen anyone drink so much.”

That was a jolt. Could a star quarterback be a drunk? That didn’t compute. It was, after all, the pre-Ball Four world of the early 1960s when most of us knew nothing about things like Mantle’s carousing or Liston’s mob connections. Sports writers of the era, many of whom partied just as hard as Jurgensen, shielded the athletes they covered.

My young mind’s palette worked in black and white only. There were no shades of nuance. Heroes had no flaws. Or so I believed. Was Jurgensen a drunk or a hero? He couldn’t be both. Was he the pure-passing machine who’d just thrown for an NFL-high 3,723 yards? Or was he no different from those lost souls my grandmother pointed out in warning whenever we rode the 47 trolley past Vine Street’s Skid Row.

I still wasn’t sure when in April 1964, 12 days after he dealt McDonald, Jurgensen’s partner on and off the field, coach/general manager Joe Kuharich shocked Eagles fans by trading the colorful QB to Washington. I wondered if it had something to do with the then 29-year-old’s lifestyle. And I wasn’t alone. Daily News columnist Jack McKinney gave voice to what many thought was behind the incongruous trade.

“Another theory is that Jurgensen’s off-field antics, something less than that of a Boy Scout leader, may have been a factor.”

That trade, which brought pedestrian QB Norm Snead here, was a bad omen. It launched one of the longest and darkest stretches in Eagles history. They wouldn’t reach the postseason again until 1978. In those 14 intervening seasons, the team amassed a combined record of 68-122-6.

With Jurgensen, meanwhile, Washington made five playoff appearances in that span, and in his first six seasons there, he was named first- or second-team All-Pro four times.

No matter the Washington coach, Jurgensen flourished. For three seasons, he clashed with prudish Otto Graham — “He likes candy bars and milkshakes,” Jurgensen said, “and I like women and scotch” — but twice led the league in passing yards. He got along famously with Graham’s successor, Vince Lombardi. Never prone to hyperbole, Lombardi once admitted that Jurgensen “may be the best the league has ever seen.”

And he was still pretty formidable after hours, too. He became a regular at such late-night D.C.-area establishments as the Dancing Club and Maxie’s. At least twice, he was charged with driving while intoxicated.

Jurgensen ended his 18-year career in 1974 with the highest QB rating (82.62) of anyone in the pre-1978 era. Sometime in the 1980s he reportedly stopped drinking and for four decades was Washington’s drawling, plain-spoken radio analyst.

By then the NFL had changed. Its stars now endure round-the-clock scrutiny.

I’m not sure how Jurgensen would have dealt with social media, paparazzi, tabloid headlines. Would it have impacted his play? Would the DWIs have sent him to rehab? Would the whispers have become shouts?

In the end, I really don’t care.

I lost that sportswriters banquet program years ago. I lost a lot of that youthful righteousness, too. So from now on, in those corners of my mind where it’s always a sunlit Sunday at Franklin Field, I’ll remember Jurgensen simply as a gifted man with a child’s name who lofted all those beautiful spirals.