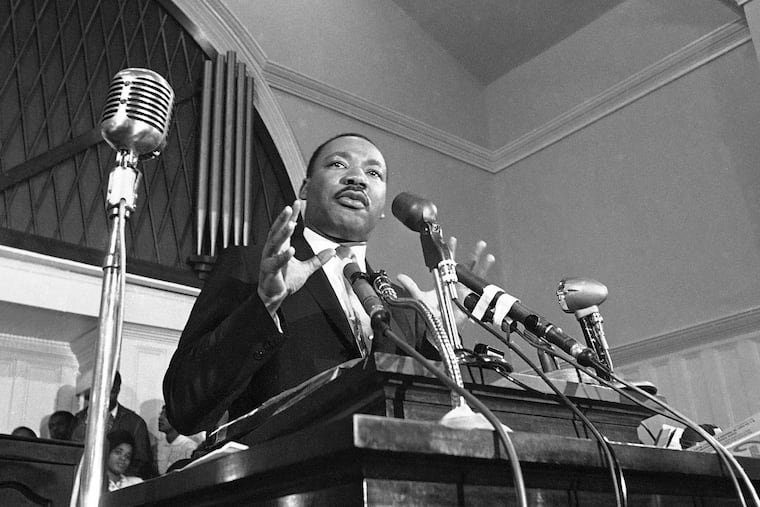

Martin Luther King Jr. spoke to Philly students in 1967. These men say it influenced the rest of their lives.

Childs Elementary will show the almost 60-year-old speech in the auditorium where King once spoke on Monday, followed by a day of service projects.

The limousine door burst open, and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stepped out onto the sidewalk in front of Dennis Kemp’s South Philadelphia school.

Kemp was 13 that day in October 1967, a member of the stage crew and the basketball team asked by the principal of Barratt Junior High to greet the school’s surprise special guest.

“In just about every Black household that I went into those days, there were three pictures hanging: Jesus, John Kennedy, and Dr. King,” said Kemp, now 72. “To actually meet this guy, it just blew me away.”

King’s historic speech, made six months before he was assassinated, had a profound effect on Kemp and many of the 800 students crowded into the school auditorium.

“What is your life’s blueprint?” King asked the students. “This is a most important and crucial period of your lives, for what you do now and what you decide now at this age may well determine which way your life shall go.”

The community will mark the historic moment Monday, on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, with a showing of the speech in the auditorium of the school now known as Childs Elementary, then a day of service projects inside the building. One group hopes to apply to have a historical marker commemorating the visit placed outside the school.

Kemp is glad that people still view and discuss King’s speech. Although he was a child, he sensed that he was part of something significant.

Though nearly 1,000 students had packed into the Barratt auditorium, crowding into aisles and leaning over balconies, the room was silent save for King’s voice, Ben Farnese, then the school’s principal, told The Inquirer in 2006. In a nearby overflow room, 450 more students watched King on closed-circuit TV.

“I took it in,” said Kemp, who was in the auditorium. “I said, ‘I’m going to keep this with me as long as I live.’”

Charles Carter, a ninth grader who was in the auditorium, remembers the quiet.

“Just figure — kids can be a little rowdy,” Carter said. “But we were transfixed, we were glued. We weren’t rowdy that day.”

Jeffrey Miles, another Barratt student, had a good seat that day. He had heard a speaker was coming to school, and he was excited — he thought it might be Georgie Woods, the prominent DJ.

After he heard King speak, he couldn’t help himself.

“I had the end seat, and I jumped up out of my seat,” said Miles, who had turned 14 a few weeks before King spoke. “The speech was so exhilarating and so electrifying, I couldn’t control myself. He was walking down the aisle with [DJ] Georgie Woods, and I said, ‘Dr. King, can I shake your hand?’”

King said yes. Miles grabbed his hand, which was sweaty — a detail that sticks in his mind, along with the sound of the Barratt students clapping thunderously for King.

A belief in ‘somebodiness’

King was in town for a “Stars for Freedom” show at the new Spectrum, opened the prior month in South Philadelphia.

“I know you’ve heard of that new impressive structure called the Spectrum, and I know you’ve heard of Harry Belafonte and Aretha Franklin and Nipsey Russell and Sidney Poitier and all of these other great and outstanding artists,” King said. He told the students to urge their parents to attend. “And I hope you will come also, for it will be a great experience and, by coming, you will be supporting the work of the Civil Rights Movement.”

King did not use notes, Farnese said. He spoke for 20 minutes, an address that would eventually be known as his “What is Your Life’s Blueprint?” speech.

The Barratt students, seventh, eighth, and ninth graders, were poised to move into a time that would determine the course of the rest of their lives.

The great civil rights figure, who had by that time already won the Nobel Peace Prize, told the young people to have “a deep belief in your own dignity, your own worth, and your own somebodiness. Don’t allow anybody to make you feel that you are nobody.”

Take pride in your color, your natural hair, King told the students, most of whom were Black.

“You need not be lured into purchasing cosmetics advertised to make you lighter, neither do you need to process your hair to make it appear straight,” King said. “I have good hair and it is as good as anybody else’s in the world. And we’ve got to believe that.”

‘Learn, baby, learn’

King urged the crowd to set upon a path to excellence, whatever that looks like.

“I say to you, my young friends, that doors are opening to each of you — doors of opportunity are opening to each of you that were not open to your mothers and your fathers,” King said. “And the great challenge facing you is to be ready to enter these doors as they open.”

Kemp remembers being surprised that King came to South Philadelphia.

“Our neighborhood was pretty poor,” said Kemp, who grew up as one of nine children in a family that struggled. “There really wasn’t too much to look forward to in our neighborhood.”

King acknowledged the “intolerable conditions” faced by many of the children he addressed. But, he said, it was incumbent on them to stay in school, to build a good life.

“Set out to do a good job and do that job so well that the living, the dead, and the unborn couldn’t do it any better,” King said. “If it falls to your lot to be a street sweeper, sweep streets like Michelangelo painted pictures.”

The civil rights hero told students to commit to “the eternal principles of beauty, love, and justice. Don’t allow anybody to pull you so low as to make you hate them.”

King, who encouraged peaceful resistance, urged “a method that can be militant, but at the same time does not destroy life or property.”

“And so our slogan must not be ‘Burn, baby, burn,’” King said, referring to a chant that had become associated with the 1965 Watts riots in Los Angeles. “It must be ‘Build, baby, build. Organize, baby, organize.’ Yes, our slogan must be ‘Learn, baby, learn’ so that we can earn, baby, earn.

“And with a powerful commitment, I believe that we can transform dark yesterdays of injustice into bright tomorrows of justice and humanity.”

‘I’ll never forget it’

Some of the members of the Barratt class in the room that day soared: Kevin Washington, who was on the basketball team with Kemp, went on to become the first Black president of the national YMCA.

Kemp was bright, but his family’s economic struggles weighed on him, he said. He dreamed of college, but it wasn’t in reach. He ended up leaving South Philadelphia High without a diploma, eventually earning a GED.

He raised children, built a life working — often in maintenance. He spent time as a school basketball coach.

After suffering medical and marital issues, Kemp fell on hard times. He spent four months without a home, sleeping in parks and at 30th Street Station.

“Dr. King’s speech really helped,” he said. “That used to come to mind when I was on the street. I’ll never forget it.”

Kemp rallied; he now lives in an apartment in South Philadelphia.

The speech also altered the course of Miles’ life.

“I was a member of a gang in South Philly,” said Miles, now 72. “I never paid attention to adults and teachers. But that day I paid attention to Dr. King.”

King’s words — reach for more, do your best, no matter your struggles — resonated. He buckled down at school, graduated from high school, from college. He became an optician and even taught students at Salus University.

“When Dr. King said, ‘instead of burn, baby, burn, learn, baby learn,’ that gave me a window,” said Miles, who lives in West Oak Lane. “It gave me hope.”