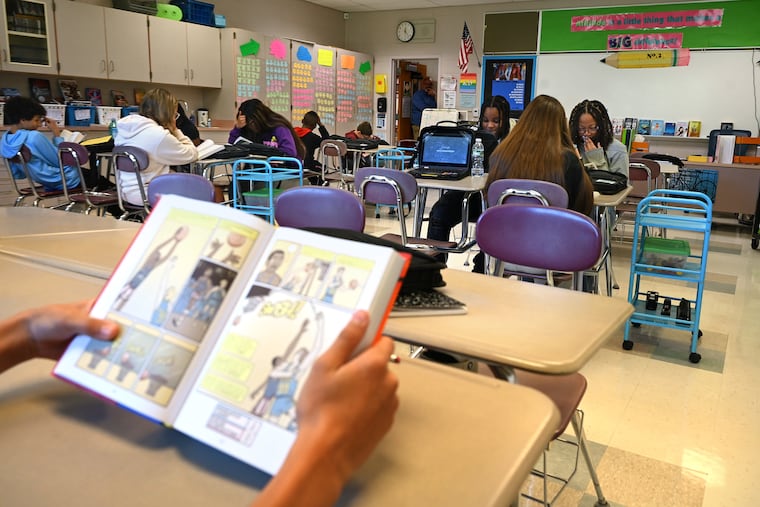

Philly is ‘inundated’ with teachers who lack full certification

One in three teachers in the lowest-performing schools is not fully certified. As the district relies on emergency certifications, data show those who come to the profession that way often don't stay.

One of every three teachers in Philadelphia’s lowest-performing schools is not fully certified.

The rate of emergency-certified teachers in the Philadelphia School District as a whole is slightly better, at 21% this school year. But amid a teacher shortage, it’s 33% in the district’s 50 most academically struggling schools, the school board heard last week.

“I’m particularly concerned about the emergency-certified teacher issue,” board member Joyce Wilkerson said at a school board progress monitoring session last week.

As part of its efforts, the school board has said it wants to do periodic deep-dives on data that measure how the school system is faring. Last week, it examined emergency-certified teacher rates and rates of repair on bathroom and installation of water-bottle filling stations as a proxy for whether schools are clean, safe, and well-supported.

» READ MORE: The number of Philly teachers without full certification has more than doubled. It comes at a cost.

The board took no immediate action on the information but said it will guide how it allocates resources and directs the administration going forward.

Here’s what it found:

Emergency-certified teachers are more common — especially in struggling schools

Philadelphia’s school system is increasingly relying on emergency-certified educators to staff its classrooms. (The numbers are up generally in Pennsylvania, but nowhere is the use of uncertified teachers as pronounced as it is in Philadelphia.)

If no certified teacher is available to fill a classroom spot, teachers can be hired on an emergency certificate if they hold a bachelor’s degree in any subject — an exception is made for career and technical education teachers.

Emergency-qualified teachers are obligated to either be enrolled in a teacher-certification program or pass exams while they teach full time, and they have until the end of the school year to finish their coursework or pass the exams. (Emergency certificates can be renewed, but not indefinitely.)

The percentage of non-certified teachers in the district is up year over year — in the 2024-25 school year, 16% of the teaching force district-wide was emergency-certified, meaning this year saw a 5 percentage point increase.

For the 50 lowest-performing schools, 26% of the teacher corps was not fully certified last year — this year, that’s up by 7 percentage points.

The disparity is not much of a surprise.

“Nationally, the most effective and highly certified teachers are less likely to teach in schools serving economically-disadvantaged or minority students, and we see this reflected in the district, where higher percentages of teachers with emergency certifications are teaching in schools with lower academic outcomes and higher level of student need,” said Tonya Wolford, the district’s Chief of Evaluation, Research and Accountability.

Though some emergency-prepared teachers go on to thrive in the system and stay long term, data show that most don’t manage to earn credentials on time or stay in public schools long term, leading to higher rates of staff turnover and instability for students.

Emergency-certified teachers typically have no training in classroom management and pedagogy and often struggle, experts say.

How to fix it?

Officials pointed out steps the district is taking to support emergency-certified teachers — both with on-the-job coaching and help to earn the credits and pass certification exams they need to convert their emergency credentials into permanent ones, as well as financial assistance to do so.

But board member Wilkerson asked Superintendent Tony B. Watlington Sr. what the district’s strategy is long term.

“Are we ever going to evolve beyond the crisis so that we are not starting school years with schools just inundated with emergency-certified teachers?” Wilkerson asked.

Not under the current conditions, Watlington said, with a nationwide teacher shortage and eroding public perception of teachers.

“What we really need is a federal- and state-funded initiative to pay for bright people, young or older, to go to a college of education to get a teaching degree and certification, and to pass the Praxis test, and to do it debt free,” Watlington said.

“Unfortunately,” he said, “we don’t have those kind of inputs at the federal or state level the way they need to be. So until then, we’re going to have to continue to be creative and to build the bench.”

Board member Whitney Jones said he was particularly alarmed at the disparity in rates of emergency-certified teachers systemwide.

“I’ll just say my hope is that over the next year or two, what we’ll see is at minimum, parity where the lowest 50 performing schools do not have this gap in certification of teachers compared to the rest of the district, and if we’re really talking about equity — where the kids with the highest need get the most investment — I would like to see the lowest 50 performing schools have a threshold or a benchmark that is lower than the rest of the district,” Jones said.

Watlington said that his aim is to get the best teachers in front of the neediest students but that “you can’t fix it just by assigning people. You have to incentivize folks to be in some places because they have free market over their labor. And school districts that have just gone the direction of just assigning people, what they find is people leave and they transfer to other places, and it just kind of backfires.”

The district, with the blessing of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, does pay bonuses to some teachers who agree to work in hard-to-staff schools. But other districts — including Camden, locally — pay bigger bonuses.