Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Born To Run’ is turning 50. Is it the Boss’ greatest album?

The album lifted Springsteen up to the cultural plateau where, remarkably, he still finds himself a half-century later.

Bruce Springsteen was always shooting for the stars.

In his 2016 memoir, he talks about making plans for world domination with his first boss, early 1970s manager Mike Appel.

“We weren’t aiming for a few successful records and some modest hits. We were aiming for impact, for influence, for the top rung of what recording artists are capable of achieving,” he wrote. “I wanted to collide with the times and create a voice that had musical, social and cultural impact.”

The crucible in which Springsteen hoped to prove he was up to that task was the recording of Born to Run, his majestic third album that was released 50 years ago, and also gave a name to his memoir.

The tortuous road to fruition of the Boss’ breakthrough album — complete with singles leaked to Philadelphia DJs and Springsteen tossing an acetate of the finished work into a Kutztown, Pa., swimming pool in disgust — is chronicled in Peter Ames Carlin’s assiduous new Tonight in Jungleland: The Making of Born To Run (Doubleday).

The book details the drama of creating an acknowledged classic that would most likely win a poll of Springsteen fans as to what their favorite album is. (Is it mine? Read on.)

His first two albums, Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J. and The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, both released in 1973, were well reviewed but hadn’t sold well. Born to Run was a high stakes enterprise, as well as a key transitional moment, in Springsteen’s career.

He already had a stronghold in Philadelphia, however, and more precisely, at the Main Point in Bryn Mawr. There, the E Street Band played an astounding 45 shows in 24 nights between January 1973 and February 1975. But while the legend of Springsteen’s live show was growing, his three-album deal with Columbia Records executives was ready to expire.

He was prone to self-loathing, which led to the Kutztown tantrum, when he decided that the eight-song masterwork he had just completed was utter garbage not worthy of release. But along with self-doubt, he had plenty of swagger.

“Of course I thought I was a phony — that is the way of the artist,” he wrote in his memoir. “But I also thought I was the realest thing you’d ever seen.”

In Tonight in Jungleland, he tells Carlin that while recording Born to Run: “I was concerned with only one thing, which was making an absolutely great rock ‘n’ roll record. … I was on a mission. I gathered my disciples around me, and we were in. We were going for the throat.”

Mission accomplished.

Born to Run was rapturously received and, by October, had landed Springsteen simultaneously on the cover of Time and Newsweek. At a New Year’s Eve show that year at the Tower Theater in Upper Darby, he waxed philosophical about that accomplishment:

“Seasons come, seasons go, you get your picture on the cover of Time and Newsweek,” he said with a shrug before “Does This Bus Stop at 82nd Street?” in a show that demonstrates the wildcat energy of the E Street Band of that era.

(It’s one of 342 Springsteen concerts streaming, including five from the “Born to Run Tour” on the Philly-based live music platform Nugs.net.)

Born to Run lifted Springsteen to the cultural plateau he’d been aiming for — where, remarkably, he still finds himself a half-century later.

These days, he’s buddies with one American president and under the skin of another. And is set to see Deliver Me From Nowhere, the Jeremy Allen White-starring biopic due in October centered on another landmark album, 1982’s Nebraska.

The story of Born to Run’s birth contains plenty of detail likely unknown to even die-hard fans.

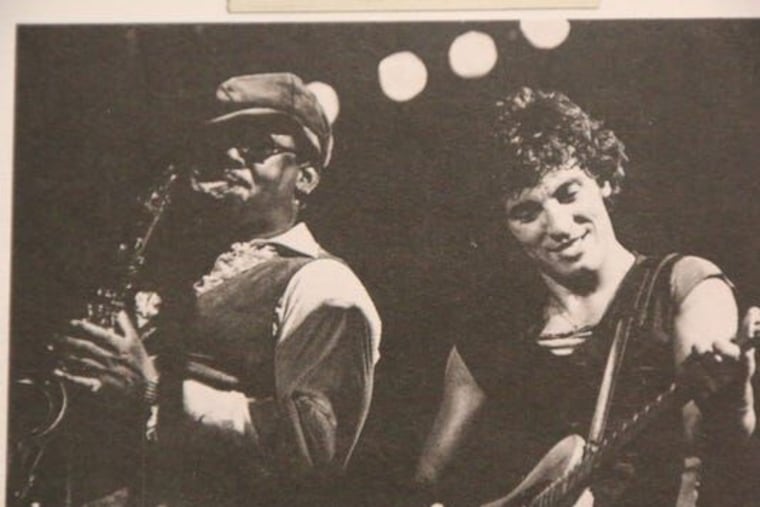

There’s a tale of racism at the Jersey Shore, when E Street keyboard player David Sancious and Springsteen are threatened by thugs on Long Beach Island, a situation that’s defused when 6-foot-5 saxophonist Clarence Clemons showed up beside his skinny friends.

Also news to this Springsteen nerd: Roy Bittan’s piano part on the B-movie fugue “Meeting Across the River,” which Appel championed over the objections of Springsteen and Jon Landau — who would soon replace Appel as the Boss’ manager — was inspired by jazz sax player Pharaoh Sanders.

There’s plenty of Philadelphia in the saga.

Randy Brecker, the Grammy-winning trumpeter from Cheltenham, plays on “Meeting Across the River.” He was joined by his late sax playing brother Michael on “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out,” on a buoyant arrangement cooked up on the spot by Steve Van Zandt, who was not yet an E Street Band member.

And late WMMR-FM (93.3) DJ Ed Sciaky plays a key role. Appel supplied him with a prerelease version of the “Born to Run” single in 1974, correctly calculating that radio play for the powerhouse track would get the suits at Columbia off their back.

Tonight in Jungleland also tracks the E Street Band’s transition away from the improvisatory ensemble of The Wild, the Innocent. That loosey-goosey style is still preferred by many old head Philly fans who recall the Main Point glory days before the world discovered Philly’s Springsteen secret.

With Born to Run, E Street became tighter and more aggressive, reflecting Springsteen’s focused vision and unplanned personnel changes.

Sancious left the band in 1974 when offered his own record deal, taking nimble drummer Ernest “Boom” Carter with him. Bittan and straight-ahead drummer Max Weinberg replaced them.

“Suddenly,” Springsteen says in Tonight in Jungleland, “we had a very different group sound, and we had streamlined ourselves into not a rock and soul band, but into a tight little five-piece rock ’n’ roll band.”

Did the music of Springsteen, Bittan, and Weinberg — with organ player Danny Federici and bassist Garry Tallent, plus auxiliary players like violinist Suki Lahav — make the greatest Bruce Springsteen album ever?

Maybe. It’s a pretty flawless record. And a necessary one in Springsteen’s evolution, a heroic getaway that shifts into overdrive and personalizes the promise of the accelerating Chuck Berry rock and roll that Springsteen felt deep down in his bones.

I still get chills every time the romantic quest that is at the album’s core is put into words as a lights-up encore at every show: “I want to know if love is wild / girl, I want to know if love is real.” You can’t beat it.

And as a no-skips experience in which every song achieves exactly what it sets out to do, its only real competition is Nebraska, whose nearly nihilistic vision is the antithesis of Born to Run’s operatic catharsis.

But neither are my personal favorite. That would be 1978’s Darkness on the Edge of Town, where open-road possibility meets up with the real world claustrophobia, and Springsteen’s protagonists are left with no alternative but to dig in and declare “It ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive!”

Maybe that preference is because Darkness was the first Springsteen album to hit me in real time, when I was a teenager at the Jersey Shore, ready to get walloped by it. And it’s surely because its existential and working-class concerns are the key to understanding everything Springsteen has done since.

And it might also have something to do with the difference between the two albums that’s articulated by Van Zandt in Carlin’s book.

Born To Run is about “the guy who leaves,” says Springsteen’s consigliere, while Darkness is not about escape from reality, but coping with it. It’s about “the guy who stays.”

If I’m still around, I can expand on that idea on Darkness’ 50th anniversary, three years from now.