It’s ‘Nebraska’ season: the Bruce Springsteen album has spawned a movie and a box set

Both "Springsteen: Delivery From Nowhere," the movie based on Warren Zanes’ book, and the fabled "Electric Nebraska" session arrive this month.

Nebraska holds its own unique, almost mystical place in Bruce Springsteen lore.

The three albums that preceded it as Springsteen established himself as a mature, arena-size artist all had arduous gestation periods. It took him six months just to write and record the song “Born to Run,” and sessions for Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978) and The River (1980) each lasted over a year.

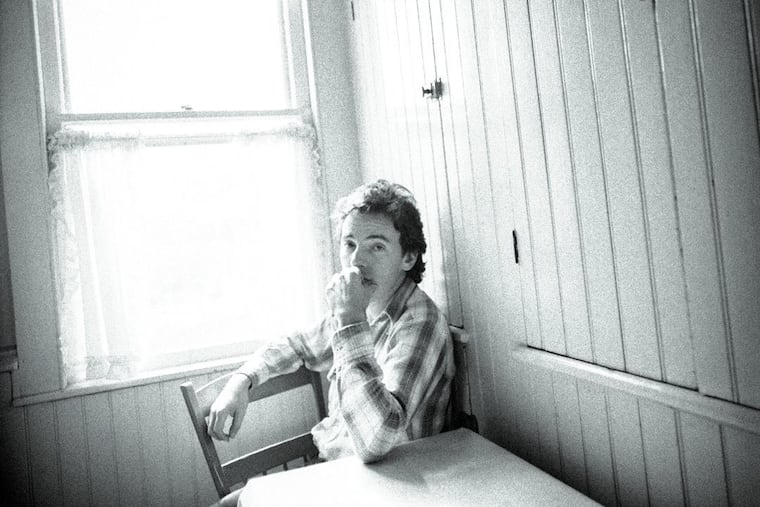

By contrast, Nebraska came quickly, with Springsteen writing and recording an indelible set of haunted, harrowing songs in just a few weeks in a rented house in Colts Neck, N.J., as he was coming off the road after “The River Tour” in 1981.

The songs were born under the influence of Terrence Malick’s 1973 movie Badlands, Southern gothic author Flannery O’Connor’s The Complete Stories, Robert Frank’s photo book The Americans, New York electro duo Suicide’s “Frankie Teardrop,” and Springsteen’s own debilitating depression.

The story of how Nebraska came about is told in Scott Cooper’s Jeremy Allen White-starring movie Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere (which premiered at the New York Film Festival last month) and mapped out in a new box set, Nebraska ’82, which includes the fabled previously unheard Electric Nebraska sessions, featuring solo Springsteen songs plugged in with the E Street Band.

The twin releases, both out Oct. 24, go deep on a pivotal period in Springsteen’s life, exploring how fear, anxiety, and a profound sense of isolation resulted in an austere 10-song masterpiece.

Nebraska is the most noncommercial music Springsteen ever made.

And yet, it set the stage for his explosion into global superstardom two years later, by clearing his conscience of any doubts about his ambivalence toward fame. It was an art-for-art’s-sake release made out of personal compulsion. With this uncompromised tour de force under his belt, he was free to reach for the brass ring with Born in the U.S.A., in 1984.

When Nebraska was first released in September 1982, not much was heard about Springsteen and his generational mental illness, though the figure of his brooding father, Douglas Springsteen — British actor Stephen Graham in the movie — loomed large in Springsteen’s storytelling.

The album was more often understood in the context of American dreams stifled during the recession in the early years of Ronald Reagan’s presidency.

In Warren Zanes’ excellent 2023 book Deliver Me From Nowhere: The Making of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska, the author cites Springsteen speaking to MTV’s Kurt Loder in a quote that eerily points forward to America in 2025.

“Nebraska was about American isolation: what happens to people when they’re alienated from their friends and their community and their government and their jobs.

“Because those are the things that keep you sane, that give meaning to life … and if they slip away, and you start to exist in some void where the basic constraints of society are a joke, then life becomes a kind of a joke. And anything can happen.”

Springsteen wrote about his battle with depression that impacted Nebraska in his 2016 memoir Born to Run — including what he’s called “my first breakdown” in the midst of a cross-country trip after the album was completed.

» READ MORE: ‘America is worth fighting for’: Bruce Springsteen performs at NY screening of Springsteen biopic

That’s a central theme in the movie, along with the importance of sticking to your principles in creating artwork that has a chance to stand the test of time.

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere tells us how Springsteen and his creative helpers learned to leave well enough alone and let Nebraska’s mystery be. Credit for that goes principally to Springsteen’s manager, coproducer, and confidant Jon Landau, who ought to be delighted by his portrayal by Jeremy Strong as an intensely loyal, empathetic collaborator and friend.

(Australian actress Odessa Young, who plays Springsteen’s love interest, is also especially good, particularly when telling White as Springsteen what an emotional scaredy-cat he is.)

Nebraska was famously recorded on a four-track recorder in Springsteen’s orange shag-carpeted bedroom in Colts Neck. It was mixed on a boom box that was water damaged when it fell in the Navesink River during Springsteen’s canoe outing with bassist Garry Tallent.

The cassette was passed around without a case as Springsteen and his crew attempted to turn the songs into fleshed-out productions.

They gave it a go with songs like the Nebraska title cut, inspired by 1950s teenage spree killer Charlie Starkweather, and “Open All Night,” the ripping ride down the Jersey Turnpike with a plea for salvation: “Hey Mr. DJ, won’t you hear my last prayer / Hey ho rock ‘n’ roll, deliver me from nowhere.”

Springsteen and his band also worked up songs that would end up on Nebraska’s follow-up like “Downbound Train,” “Working on the Highway,” and “Born in the U.S.A.”

White, who turns in an intelligent, sensitive performance that never quite convinced me that I was looking at Bruce Springsteen, leads a band of musician actors who look pretty much like the members of the E Street Band. They pull off a studio version of the Boss’ rocked-out red, white, and blue protest song effectively.

The meat of the Nebraska ’82 box is the eight-song Electric Nebraska disc, plus nine outtakes. They draw from the same well of vintage Robert Johnson and Woody Guthrie recordings, 1950s rockabilly, and pulp fiction storytelling that fueled Springsteen at the time.

The box also contains a remastered version of the original Nebraska, and a new black-and-white live performance film shot at the Count Basie Theater in Red Bank, N.J., with Springsteen accompanied at times by guitarist Larry Campbell and E Street keyboard player Charlie Giordano. It’s a vigorous performance of the album in its entirety, which had never previously been done.

Among the outtakes, there’s a slow, spooky “Pink Cadillac,” and an early “Working on the Highway” version called “Child Bride,” whose protagonist winds up behind bars.

“On the Prowl” is reverb-drenched for Halloween season, with horny Bruce turning beastly: “They got a name for Dracula and Frankenstein son / They ain’t got no name now for this thing that I’ve become.”

More serious is “Gun In Every Home,” a keeper about parenthood — which Springsteen had not yet experienced — and a vision of a fully armed suburban America that feels prescient. “Two cars in each garage, and a gun in every home.”

And what about Electric Nebraska itself? Does it turn out to be the switched on Boss meisterwork that turns up the volume and sonic fidelity and improves on the lo-fi original?

Well, no. It’s still a fascinating document, and all serious Springsteen fans are going to want to hear it.

Some of it will sound familiar. “Atlantic City,” about resuscitation of the spirit in a boardwalk town, is delivered in a full-band arrangement that’s basically the same as Springsteen does onstage. It also has tweaked lyrics: “I’m going down half,” the singer promises himself. “I’m comin’ back whole.”

The desperate “Johnny 99” is also presented with a rollicking Chuck Berry glee, much like it has been in Springsteen’s live shows.

“Nebraska,” “Mansion on the Hill,” and “Reason To Believe” are more subtly altered, adding tasteful accents to the songs.

And the real attention grabber is a high voltage “Downbound Train,” which sounds as if it was recorded after consuming several venti lattes. It’ll shake you up for sure, but the slower, gloomier take on “Born in the U.S.A.” is more powerful.

Electric Nebraska, in essence, cements the argument made in the Deliver Me From Nowhere movie: When real magic happens, the best course of action is to leave it be.

Springsteen has written that in recording Nebraska, his goal was to make himself “as invisible as possible,” the better to make the people in his songs come starkly to life.

On Electric Nebraska, his presence reemerges, and the songs in some ways sound better. But the characters who are so vividly alive on that poorly recorded cassette start to disappear as the fidelity improves.

No matter how much effort was made to improve them, the songs, as Landau told Zanes, “resisted intervention.”

Forty-three years after its release, the original Nebraska remains unmatched.