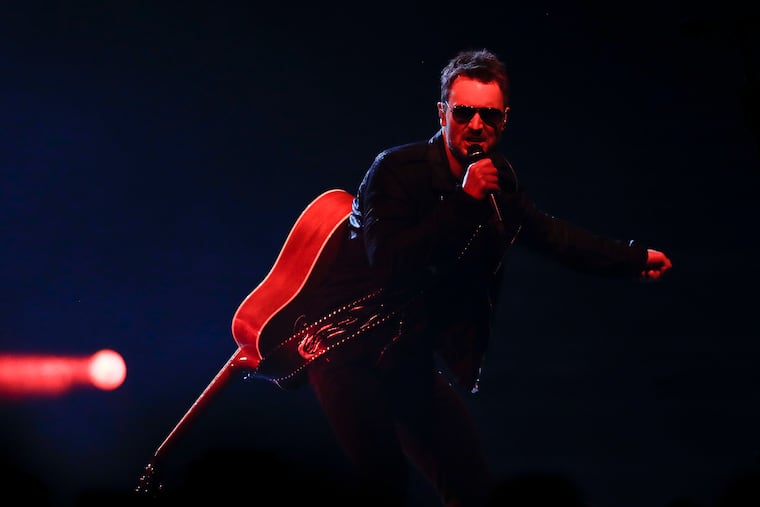

Country outlaw Eric Church, in the first of two marathon shows at the Wells Fargo Center

In his leather jacket and aviator shades, the workmanlike performer emphasizes a rebellious streak that ardent followers who raise beer cans high in “Drink In My Hand” or “Cold One” see in themselves.

Eric Church only works weekends.

On Friday in South Philadelphia, the North Carolina-bred, self-styled country music outlaw played a show that stretched to three hours (if you include a 20-minute intermission) at the Wells Fargo Center.

And on Saturday, he was set to do it again, albeit with a substantially different set list. Together, the back-to-back marathons comprise the Philadelphia stop on Church’s Double Down tour, which takes the working week off and gets down to business in a new city just as his fan base is ready to get rowdy.

Much of country’s success in the post-Garth Brooks era has been due to turning up the volume and appropriating arena-rock staging while sticking to small town signifiers to reassure fans that the music belongs to them.

Church plays in that ballpark far more credibly than most. In his leather jacket and aviator shades, he emphasizes a rebellious streak that ardent followers who raise beer cans high in “Drink In My Hand” or “Cold One” see in themselves.

Taking the stage at 8:45 p.m with no opening act, Church opened with “That’s Damn Rock & Roll,” from his 2014 album The Outsiders. It was the first of many snarling songs to feature lead guitar fireworks by former Black Crowes member Jeff Cease and wailing vocals by singer Joanna Cotten.

As Church and Cotten moved out on the horseshoe-shaped runway, the song made reference to Elvis Presley, Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, and defined its subject as not being “a middle finger on a T-shirt the establishment’s trying to sell,” but something more authentic, such as “a rock through a window” or “Give all ya got till there ain’t nothin‘ left.”

With an acoustic guitar frequently slung around on his back, Church makes plain that’s what he and his bandmates plan to do. He’s a workmanlike performer intent on taking the time to get the job done.

That meant underscoring his Middle America bona fides early on in “How ‘Bout You,” from 2006’s Sinners Like Me, a song whose references to nose rings and baggy clothes as the antithesis of his own scuffed-up cowboy boots style have grown dated.

It also meant giving props to a long line of individualists Church associates himself with. “How ‘Bout You” weaved its way into Waylon Jennings “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?” and Ram Jam’s 1970s hit “Black Betty,” based on an African American work song credited to Leadbelly.

Later, he sang a verse of Hank Williams’ “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” kicked off the second set with a surprise, winningly gruff solo acoustic cover of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” and honored Merle Haggard with “Pledge Allegiance To The Hag,” which, oddly, is a blustery rock rather than a country song.

Church performed at the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas two days before a gunman killed 58 people in 2017, an event that led him to speak out against the National Rifle Association. On Friday, he brought up the tragedy in connection to “Monsters,” a song written for his youngest son, trying to confront the childhood fears that are maybe not so imaginary after all.

The leisurely pace allowed for audience participation. During “These Boots,” people took off their shoes and waved them in the air. On “Jack Daniels,” the 42-year-old singer shared airplane bottle-sized shots with fans.

“Record Year,” about getting over heartache with the aid of Willie Nelson and Stevie Wonder, found Church signing album covers, including one with a picture of Haggard holding a chihuahua, which Church described as “the most rock-and-roll thing in the history of country music.”

The last notable name Church dropped was “Springsteen,” the title of a 2012 hit that was the last tune of the night before the closing song of self-reliance, “Holding My Own.” Church’s wistful ode to the Boss is about the way music marks time and triggers memories (a motif also expertly explored in Taylor Swift’s 2006 single “Tim McGraw”).

It’s saved for almost last because of the importance of the song’s subject to Church. The rock-till-you-drop marathon filled with songs of faith, family, frustration and (mostly) celebration is clearly modeled after Springsteen. And while Church’s music doesn’t reach the inspirational heights of the Jersey rocker or his other heroes, the country star is a rock-solid songwriter and effective crowd-pleaser who’s more than capable of holding his own.