Michael Jackson is dead already. Is he now canceled too?

Brace yourselves, Michael Jackson fans. Cancel culture is coming for the King of Pop.

Brace yourselves, Michael Jackson fans.

Cancel culture is coming for the King of Pop.

The list of powerful men in the public eye who have been accused of being sexual predators since the Harvey Weinstein story inaugurated the #MeToo era in 2017 is long and getting longer.

The reckoning for past and present misdeeds has been slow to come to the music industry, however, where a tradition of loose morality toward louche behavior has long been used as an excuse for boys-will-be-boys transgressions among the money-earning headliners the industry feeds off.

But 2019 has gotten off to a fast and sordid start for alleged predators. In January, R. Kelly, the soul-singing star known as “the Pied Piper of R&B” who has been suspected of preying on underage girls for a quarter-century, was the focus of a six-hour Lifetime cable series full of stomach-turning allegations made by accusers who summoned the courage to look the camera in the eye.

On Friday, Kelly was charged with 10 counts of aggravated sexual abuse.

This month, Ryan Adams, the acclaimed indie rock songwriter who came to prominence as leader of the North Carolina band Whiskeytown in the 1990s and who was married to singer-actress Mandy Moore, was the subject of a New York Times report in which seven women claimed he offered to aid their careers before making sexual advances.

The story also alleges that Adams, 44, had inappropriate sexual communication with a now-20-year-old woman when she was 14 and 15. It’s now the subject of an FBI investigation.

Adams has denied the allegations.

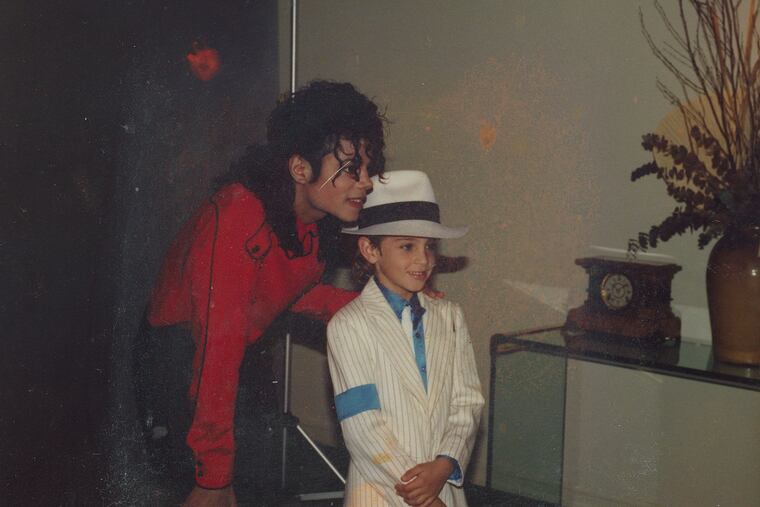

And now comes the big one: Beginning Sunday, March 3, HBO will run the two-part, four-hour documentary Leaving Neverland, in which two men detail the sexual abuse they say Jackson committed against them when they were children, starting in the case of Australian choreographer Wade Robson when he was just 7 years old.

The film, directed by Dan Reed, kicked up a firestorm when it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival last month. It has been dismissed by the late superstar’s estate as “the kind of tabloid character assassination that Michael Jackson endured in life, and now in death.” Jackson’s estate is suing HBO for $100 million.

The predatory behavior alleged by Robson — who met Jackson when he won a dance contest in Brisbane at age 5 — and James Safechuck, a child actor who starred with the singer in a Pepsi commercial at age 10, in many ways fits with the transactional nature of sexual abuse that’s been the pattern within the entertainment industry (and the workplace at large) since time immemorial.

It’s the “Have sex with me and I’ll help your career” modus operandi, or the more menacing “If you don’t have sex with me, I’ll end your career" tactic alleged to have been wielded by movie exec Weinstein and CBS TV boss Les Moonves.

It also fits with the charges leveled against Adams, who’s accused of mentoring young songwriters such as Courtney Jaye and Phoebe Bridgers (who wrote her song “Motion Sickness” about him) and then attempting to sexualize their relationships.

Adams is not yet completely canceled: His songs are still heard on Spotify playlists like “Chill as Folk" and “Roots Rising.” But his career has taken a serious hit. Big Colors, the first of three albums he planned to release this year, is no longer scheduled to come out in April. Variety reported that three music gear companies have ended sponsorship deals with him.

The Adams allegations also likely represent “the tip of an indie music iceberg,” as critic Laura Snapes wrote in a Guardian essay. At the very least, the charges against Adams have spurred a discussion about the ways in which women are pressured to compromise themselves to get ahead in a business in which gatekeeping and decision-making power tend to be concentrated in the hands of men.

In Leaving Neverland’s story, it’s Jackson who holds the power. The circumstances are different from most cases of reported entertainment industry abuse, because the allegations involve a grown man and preadolescent boys.

The transactional power dynamic still exists, though. In this case, it’s not the victims who made deals seeking success, but their parents, lured by the promise of fame and fortune.

They’re wooed by getaways to the fantasy world of Jackson’s Neverland ranch, or just wowed by their relationship with a superstar so lonely that he wants nothing more than to spend all day at his own private amusement park with their children.

From there, a trust develops that’s so complete the boys’ mothers are willing to let their children sleep in the locked bedroom of a grown man.

In the HBO version of events, what the kids get from the transaction is love. The movie tells the parallel stories of Robson and Safechuck, both drawn into relationships with Jackson where they become the single most important fixation of the world’s most popular entertainer.

That is, until they were replaced by other young friends, such as Macauley Culkin and Brett Barnes, both of whom say Jackson never acted sexually inappropriately with them.

Leaving Neverland doesn’t attack Jackson with “gotcha!” tabloid attitude. Instead, it builds a slow, inexorable, and heartbreaking case by drawing viewers in through soft-spoken interviews with Robson and Safechuck and their families, who say Jackson befriended them before using and betraying them. As Robson’s grandmother says, “Michael ruined a lot of lives.”

The Jackson estate has slammed Safechuck, 40, and Robson, 35, as “two admitted liars.” Both men have given sworn testimony that Jackson never sexually abused them. Robson’s testimony in particular was crucial in Jackson’s acquittal in 2005 on child molestation charges in a case that followed a 2003 one in which charges by the family of another boy were settled out of court for $23 million.

Both men now say that they were manipulated by Jackson at the time to speak on his behalf, and that they were also motivated to do so to get back in his good graces. In Robson’s case, he wanted to save his hero from going to prison.

But whether you choose to believe Jackson’s accusers or the fervent denial by his estate, or Jackson himself heard in the film, you might wonder: What difference does it make? He’s already dead, isn’t he?

He is. And that, in some ways, has been the key to his popularity.

In 2009, when Jackson died from a combination of drugs that was ruled a homicide, for which his personal physician was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter, it did wonders for his career.

At the time of his death, Jackson was rehearsing This Is It, a planned comeback for which 50 sold-out shows were planned in London’s O2 arena. But in the decade before, things were not going so well for the wildly popular entertainer, the third-biggest-selling recording artist of all time behind the Beatles and Elvis Presley.

Although Jackson was never convicted of a crime, the sexual molestation allegations, the transformation of his physical appearance with ever-whitening skin, and his bizarre behavior (such as dangling his child over a hotel balcony in Berlin in 2002) had diminished his reputation. He was the butt of jokes on late-night TV, “Wacko Jacko” in the British tabloids. He hadn’t performed a full concert tour in the U.S. since Bad in 1989.

Dying changed all that. Jackson’s death inspired an outpouring of grief that has not been matched by a celebrity death since, and his exit from this mortal coil has allowed fans to push all the unpleasantness aside and focus on everything they cherish about the musical and performative genius of the beloved entertainer.

Jackson’s millions of admirers have been free to get the night going with “Wanna Be Startin‘ Somethin'” and keep the party going with “Billie Jean.” And it’s also been financially beneficial to his estate, which, according to Forbes, pulled in a whopping $825 million in 2016, topping the magazine’s dead celebrity list.

The devastating HBO documentary represents a threat to that comfortable state of affairs. Already, the trial run of a Jackson jukebox musical called Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough with a book by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Lynn Nottage has canceled its Chicago run, and producers say it’s instead scheduled to go straight to Broadway in 2020.

Will the new stories of Jackson’s alleged sexual abuse result in his being completely and effectively canceled? Of course not. Jackson is far too beloved and ingrained in people’s lives ever to be erased. But since his death, it’s been easy enough for the culture to collectively push the half-remembered allegations aside and instead simply appreciate the genius of Michael Jackson.

After watching Leaving Neverland, that’s not so easy to do.