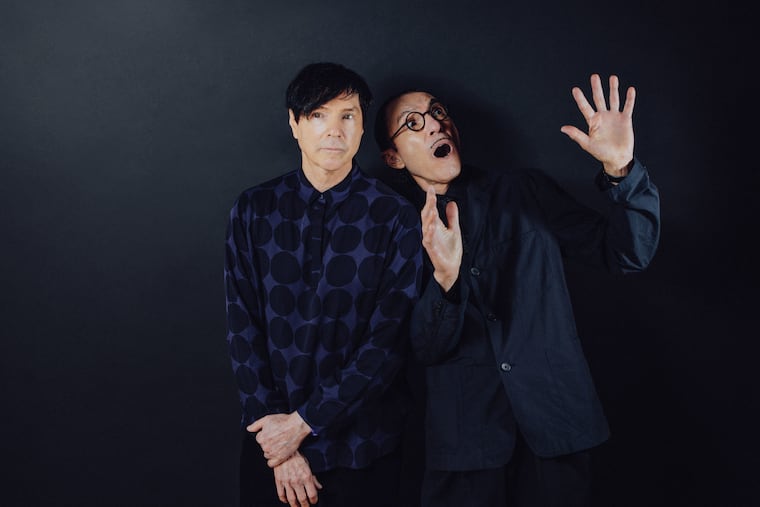

Meet ‘your favorite band’s favorite band’ in Edgar Wright’s new documentary, ‘The Sparks Brothers’

Brothers Ron and Russell Mael have carried on for over 50 years as Sparks, influencing all manners of acts. The “Shaun of the Dead” director has been a fan since he was a kid.

There’s a scene in The Sparks Brothers, director Edgar Wright’s movie about the hugely influential art-pop duo Ron and Russell Mael, in which the siblings are asked why they had never before agreed to do a documentary film about their fabulously unpredictable 50-year-plus career.

“We didn’t want to do the standard documentary full of talking heads,” says Ron Mael, the brother with the mustache who’s the band’s principal songwriter. His singing sibling Russell concurs: “It would become too dry.”

To emphasize that he has no intention of letting that happen to The Sparks Brothers — which opens Friday at the Ritz Five and at select theaters in the suburbs — Wright resorts in the movie to a slapstick gag: He tosses water in the Maels’ faces.

» COME JOIN US: Join music critic Dan DeLuca and Philly singer-songwriter Carsie Blanton on Inquirer Live Thursday at 5 p.m. Click here to register.

“That was the physical representation of the fear of it being too dry,” says Ron Mael with a laugh, speaking from Los Angeles via Zoom. “We were worried that a documentary would be so much more boring than what we do as a band. But when we met Edgar, we realized we didn’t have to worry about that.”

On screen, Wright is identified as a Sparks “fanboy.” And the Maels — who grew up in Southern California and studied film and theater at UCLA before recording with producer Todd Rundgren in 1971 — were fans of Wright films like 2004′s Shaun of the Dead and the music-mad 2017 action movie Baby Driver.

“He has a passion for music,” Ron Mael says. “And the other important thing was that he didn’t want to fixate on the past, but wanted to treat all the periods of our career in a balanced way.”

Over 25 albums, “our band has had a really different kind of career trajectory,” says Russell Mael, also zooming from Los Angeles, “and Edgar wanted to tell that whole story.”

Wright first saw Sparks live in London in 2015 when the band was touring as FFS with Scottish band Franz Ferdinand.

“I was dumbfounded by how amazing it was,” Wright says. " I started saying aloud to people that somebody should do a Sparks movie … then a friend called me on it and said: ‘You should do the movie!’ "

Wright tells the Sparks story in lively fashion, with traditional and stop-motion animation, vintage film clips, and plenty of performance footage, including stops on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand and British TV show Top of the Pops.

He brings in a range of pop culture types for interviews, including Beck, Bjork, Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore, “Weird Al” Yankovic, Flea, Go-Go’s guitarist Jane Wiedlin, comedian Patton Oswalt, author Neil Gaiman, and Gilmore Girls creator Amy Sherman-Palladino.

It’s tempting to describe the ups and down of the Sparks saga as a Rollercoaster, the name of a forgotten 1977 disaster movie in which the band was the featured musical act. Those who’ve never heard of the often-satiric and under-the-radar duo might wonder: Am I watching a mockumentary? Is Sparks a real band?

Indeed, they’re real. The Maels have been either ahead of their time — or slightly out of step with it — going all the way back to 1967, when they recorded a song called “Computer Girl,” years before bands like Kraftwerk made electronic music fashionable.

The big break came when Christine Ann Frka of The GTO’s brought the brothers to Rundgren’s attention.

“It wasn’t like anything else that I was normally getting,” Rundgren says in The Sparks Brothers. Talent scouting “is sometimes like butterfly hunting: You’re looking for some species that nobody has ever discovered before.”

“We’re so indebted to Todd,” Ron Mael says. “Before we did our first album, we sent our demos out to 30 record people, and the only one who responded was Todd. (The Maels have reunited with Rundgren for “Your Fandango,” the new single from his forthcoming album Space Force.)

Sparks is often called a cult act. “I don’t want to sound like L. Ron Hubbard,” Wright says, “but maybe my job is to recruit more cult members. … If I can just turn one person who had never listened to Sparks into a Sparks fan, then I’ve done my job.”

The brothers, though, have had several periods of commercial success. They were big in England with the 1974 glam rock hit “This Town Ain’t Big Enough for Both of Us.”

In 1979, Sparks sought out Donna Summer producer Giorgio Moroder and collaborated on No. 1 In Heaven, an album that created the template — flamboyant front man, stone-faced keyboard player — followed by ’80s synth-pop duos such as Erasure and Pet Shop Boys.

Jack Antonoff, the leader of New Jersey band Bleachers and producer of Lorde, Lana Del Rey, Taylor Swift, and Pink, says, “all pop music is rearranged Vince Clarke [of Erasure] and Sparks.”

In 1994, the band scored an electronic dance hit with “When Do I Get to Sing ‘My Way’,” which references Frank Sinatra’s signature song and conveys a melancholy longing for overdue recognition.

The Spark Brothers has its share of pathos. In one animated scene, the brothers recall being recognized by a cashier in Los Angeles before paying for their groceries with food stamps.

Late in the film, Rundgren pays them the ultimate compliment: “There’s some comfort in the fact that something that weird can survive without becoming less weird.”

Sparks have been on a late-career run with their 2017 Hippopotamus, last year’s A Steady, Drip, Drip, Drip, and another movie project that has come to fruition: They wrote the script and music for Annette, French director Leos Carax’s movie starring Adam Driver and Marion Cotillard, which opens the Cannes Film Festival on July 6.

And unlike famously battling brother bands like The Kinks and Oasis, the Maels say their creative partnership is free of rancor. They’ve never broken up, and are working on their 26th album.

“We just have a real, unspoken mission statement that’s almost like a cause now, the longer we keep doing it,” Russell Mael says. “How many ways can you make a 3 1/2-minute pop song interesting? That’s the challenge, and there’s a bond between us that lets us put on blinders to the outside world and just keep making music. Because that’s what our passion is.”