Most people in the U.S. are still susceptible to the coronavirus, CDC study finds

The agency also reported that the number of actual coronavirus infections probably is higher — by two to 13 times — than the reported cases.

A small proportion of people in many parts of the United States had antibodies to the novel coronavirus as of this spring, indicating that most of the population remains highly susceptible to the pathogen, according to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The agency also reported that the number of actual coronavirus infections probably is higher - by two to 13 times - than the reported cases. The higher estimate is based on the study on antibodies, which indicates who has had the virus. The number of reported cases in the United States now stands at 3.8 million.

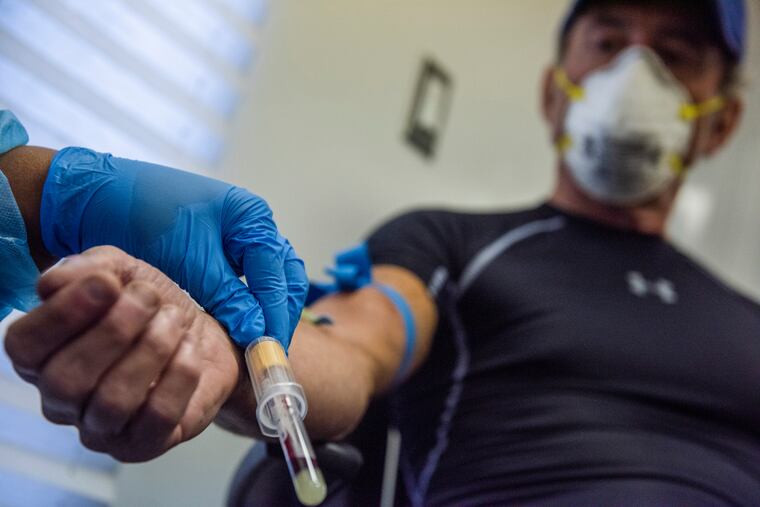

The new data appeared Tuesday in the JAMA Internal Medicine publication and on the CDC website. The information about antibodies was derived from blood samples drawn from 10 areas, including New York, Utah, Washington state and South Florida. The samples were collected in discrete periods in two rounds - one in early spring and the other several weeks later, ending in early June. For two sites, only the earlier results were available.

The blood samples were collected during routine screenings such as cholesterol tests. Such serological surveys are being conducted throughout the country as public health experts, government officials and academics try to determine the virus's course, how many people have been infected and how many have produced antibodies in response.

In New York City, almost 24% of the population had antibodies as of early May - the highest proportion by far of any of the locations but still far below the 60% to 70% threshold for herd immunity, the point at which enough people are immune to the virus, either through exposure or because they have been vaccinated. Herd immunity makes it far less likely that the virus will be transmitted from person to person.

In the other areas, the percentages of people with antibodies were in the single digits in late May and early June. That included Missouri, at 2.8%; Philadelphia, at 3.6%; and Connecticut, at 5.2%.

The new data emerged as the nation struggles with a wily pathogen that can produce no symptoms at all, or sicken and kill - 138,000 people in the United States have died of covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. Large swaths of the nation are in turmoil as many communities debate how to reopen schools this fall, wrestle with rising virus-related hospitalizations and, in some cases, roll back restrictions to restart a flailing economy.

"Most of us are likely still very vulnerable to this virus and we have a long way to go to control it," said Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist at the John Hopkins Center for Health Security. "This study should put to bed any further argument that we should allow this virus to rip through our communities in order to achieve herd immunity."

With vaccines still months or years off, some people have suggested allowing large numbers of people to become infected to speed the process of herd immunity. Many call that idea dangerous.

"The study rebukes the idea that current population-wide levels of acquired immunity (so-called herd immunity) will pose any substantial impediment to the continued propagation" of the virus, at least for now, wrote Tyler Brown and Rochelle Walensky, infectious-disease specialists at Massachusetts General Hospital, in an accompanying opinion article. "These data should also quickly dispel myths that dangerous practices like 'COVID parties' are either a sound or safe way to promote herd immunity."

"Covid parties" refer to events in which people get together in an attempt to infect themselves and develop immunity to the virus. A 30-year-old man who believed the coronavirus was a hoax and attended a "covid party" died recently after being infected with the virus, according to the chief medical officer at a Texas hospital, The New York Times reported. But the account, it said, has not been independently corroborated.

The undercount of infections was discussed late last month by CDC Director Robert Redfield, who said the actual number of infections was about 10 times the confirmed cases.

The new study gave details on the undercount: In Missouri, the estimated number of actual infections was 13 times greater than the confirmed cases. In Utah, it was at least twice as high.

"The findings may reflect the number of persons who had mild or no illness, or who did not seek medical care or undergo testing but who still may have contributed to ongoing virus transmission in the population," the study's authors wrote. Researchers say more than 40% of people who are infected do not have symptoms.

Because people often do not know they are infected, the public should continue to take steps to reduce the risk of transmitting the virus, including wearing face coverings outside the home, remaining six feet from other people, washing hands frequently and staying home when sick.

Separately, in a report in the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, a study by Indiana University and the Indiana State Department of Health found that 2.8% of state residents had been infected as of late April. It was the first randomized study to determine the prevalence of the coronavirus infection in the state. It also included members of minority communities who were not randomly selected. The study used nasal-swab tests to detect active infections and blood tests to find antibodies that indicated a past infection.

The 2.8% represented about 187,000 people, or 10 times more than the number of confirmed cases identified through conventional testing. About 44% of the infected people were asymptomatic, according to Nir Menachemi, the lead scientist on the study and a professor of public health at Indiana University. The number fell to a little over 2% in a second round of testing in early June, but in a change, more people had antibodies, indicating past infections, while fewer had active infections.

In a second report in MMWR, CDC researchers surveyed residents of two Georgia counties - DeKalb and Fulton - in late April and early May and found that 2.5% had antibodies to the coronavirus.