Young people are being left out of coronavirus economic relief efforts

There's a growing consensus among lawmakers and policy wonks that young millennials and their Generation Z counterparts need an aggressive government boost.

WASHINGTON — During the despair of the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt established ambitious federally funded jobs programs directly aimed at buoying young people.

Now, in the midst of the historic coronavirus pandemic, there's a growing consensus among lawmakers and policy wonks that young millennials and their Generation Z counterparts need the same kind of aggressive government boost. But historians doubt any government intervention of the kind that helped lift a generation of young people out of poverty in the 1930s would be workable today.

Conspicuously left out of the $2 trillion stimulus package, most high school seniors and many college students are not eligible for broad financial assistance from the government to help them dig out of the pandemic's economic hole.

Those over 16 and college students were barred from receiving stimulus checks provided either to their parents on their behalf, or to them directly if their parents claim them as dependents. Young people also lack access to broader economic benefits like relief from student loan debt from private lenders, frequently health care benefits and unemployment insurance for those who have yet to enter the job market.

"I think we forget how vulnerable young folks are," said Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Calif., in an interview.

Khanna called for any new stimulus package to include additional relief for student debt, stimulus money for high school and college students, and the creation of a federal program to give young people not bound for college the opportunity to earn a free, post-high school educational certificate.

"Their needs might not be as visible or immediate as someone who has a business they've spent 25 years building or people literally having trouble putting food on the table. But we can't have another generation lost in terms of accessing the American Dream," Khanna added.

"When you see the 2008 financial crisis, now compounded by this current crisis — you run the risk of having a generation or possibly two that feel the American Dream is slipping away from that and that's something we have to address."

» FAQ: Your coronavirus questions, answered

Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., who has been an unlikely champion of massive federal relief for American workers throughout the coronavirus crisis, is rolling out new legislation this week to bar the Department of Education from providing universities with large endowments with federal relief money unless they spend some of the funding "to help their students and cover costs of this emergency."

In some ways, history is already repeating itself for older millennials born in the 1980s and 1990s, and for their younger peers following in their footsteps.

Saddled with debt and victims of stagnant wages, financial turmoil has been a hallmark of modern young adulthood — the pandemic marks the third major crisis rocking young adults' careers and educational prospects after the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

A Wall Street Journal/ NBC News poll found voters aged 18 to 34, many of whom work in the gig economy, are more likely to be laid off during the pandemic than any other age group.

The pandemic is also likely to exacerbate existing debt and housing affordability issues. Already, 57 percent of 18 to 29 year olds carry debt and 63 percent of young adults under the age of 30 are concerned about the impact housing costs will have on their future, according to a new Harvard Youth Poll released on Thursday. Eighty five percent of young Americans favor some form of student debt relief, per the poll. Under the stimulus bill, they get some relief from federal student loan payments, which have been suspended between March 13 and Sept. 30. But private loan providers do not have to give borrowers the same break.

Maggie King, a senior at Northeastern University, was laid off from her job at a restaurant due to COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus. She's now graduating into an economy with student loans she's afraid she won't be able to pay off.

"I've always considered myself financially responsible, but I lost my restaurant job because of COVID-19, and now the savings I set aside to pay off my loans are going towards rent, groceries, and bills," King said via a statement from The Roosevelt Network, a student policy initiative where she is an organizer. "Frustration has been rising in our generation for a while, and this crisis is making things worse."

During the Great Depression, the increase in the unemployment rate was greatest for young Americans: between 1930 and 1940 it skyrocketed by 251 percent for 14 to 24 year olds.

And the government took a proactive role in trying to mitigate it. Then first lady Eleanor Roosevelt expressed angst over what would become of the nation's future by saying in 1934, "I have moments of real terror when I think we might be losing this generation."

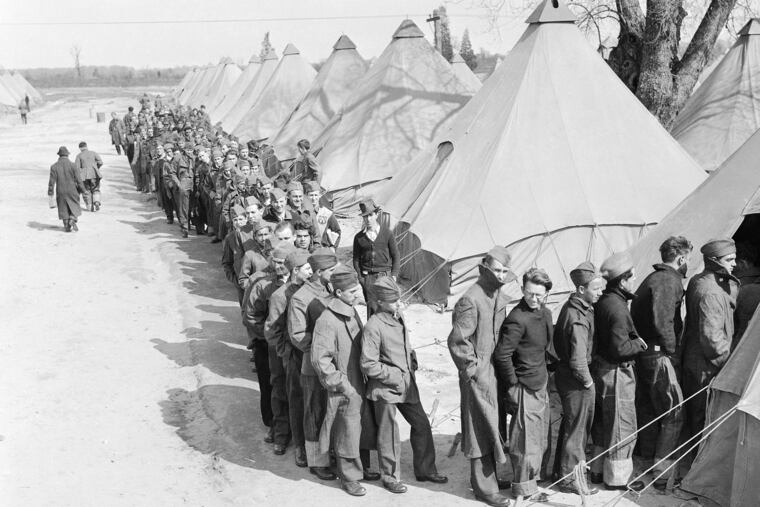

Two of the popular and ambitious programs of Roosevelt's New Deal were the Civilian Conservation Corps, established in 1933, and the National Youth Administration that followed two years later. The CCC put over three million unemployed, unmarried young men, who had largely dropped out of high school, to work during ts eight-year span in Roosevelt's so-called "Tree Army." The NYA, which was created by executive order, provided employment opportunities for young women, along with financial assistance for students to continue or finish their educations.

Like most Depression-era programs, the CCC was segregated. The NYA's first director specifically wanted to ensure the administration treated African American youth fairly, but they still encountered racism and segregation in the state branches and received less assistance than their white counterparts.

The government also stepped in to provide a smooth financial transition to civilian life for young men leaving the armed services in the post-World War II GI Bill. That sweeping legislation provided veterans with tuition to start or continue college, a cost of living stipend, unemployment benefits, job counseling, guaranteed loans to purchase homes or start businesses and more.

It resulted in an economic boom, according to Suzanne Kahn, deputy director at the Roosevelt Institute, who said similar programs were key to helping today's younger generations financially endure and thrive post-pandemic.

"I think that the problem is even in the best case scenario where you get a job — if you're entering the job market at this moment, it'll take 20 or 40 years for your wages to be where they'd be if you entered the job market at a better moment," Kahn.

She said that will make it harder for young people to save for retirement or buy their first homes, both signs of "American adulthood."

Historians who have studied the New Deal's treatment of young Americans doubt massive programs like the CCC and NYA could be replicated in today's political climate.

"If there is any kind of impulse now for anything even resembling the public works programs of the New Deal, I don't see it and anything like the CCC is particularly far off to me," said Benjamin Alexander, who teaches American history at New York City College of Technology in Brooklyn and authored a book about the Civilian Conservation Corps.

“People in the 1930s by necessity felt a need to be open to experimentation and experimentation with extraordinary powers for the federal government. The whole idea of the federal government organizing a public works project on a massive scale is an out of the ordinary role. In this day and age, it would take a popular ground-swelling — and that wasn’t what was seen in the New Deal.”