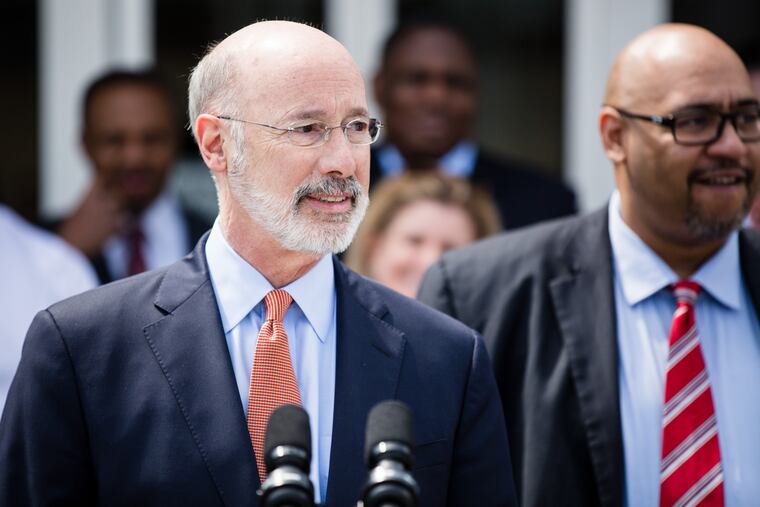

Why Gov. Tom Wolf’s big effort to grant coronavirus reprieves to Pa. inmates came up small

The Department of Corrections has defended its response, saying it was a cautious approach that included all relevant parties to represent the public interest.

Spotlight PA is an independent, nonpartisan newsroom powered by The Philadelphia Inquirer in partnership with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and PennLive/Patriot-News. Sign up for our free weekly newsletter.

HARRISBURG — In April, amid growing fear that prisons could be tinderboxes for the coronavirus, Gov. Tom Wolf announced he would grant temporary reprieves to certain nonviolent state inmates who have medical conditions that make them particularly vulnerable.

It was a power move by Wolf, who initially opted to wait for a plan from the GOP-led legislature, but reversed course after it became clear a bill would be limited to 450 people. At the time of the announcement, Wolf said: “There is a premium on speed here. We need to move quickly."

But what has unfolded since has come up short of even the Republican plan. State officials identified just over 1,200 incarcerated people who met Wolf’s conditions, but of those, only 159 have been granted a reprieve, according to data released by the administration.

Of that small group, 148 had been released as of Thursday.

Civil rights groups say there were simply too many cooks in the kitchen — stakeholders far removed from inmates, like district attorneys — while advocates for prisoners, including defense attorneys or even the inmates themselves, were excluded.

“It’s just an obvious, glaring omission,” said Elizabeth Randol, legislative director for the ACLU of Pennsylvania.

The Department of Corrections has defended its handling of the process, saying it was a cautious approach that included all relevant parties to represent the public interest. Officials screened thousands of inmates to find ones that met the governor’s criteria: older and medically vulnerable people serving time for a nonviolent offense that had no victim, who have not committed a violent crime in the last decade, and who have no active protective orders.

Only a sliver of the total inmate population, which at the time was about 47,000 people, was determined to be qualified for release. And even among that smaller pool, some say they have been waiting for weeks on word of what is happening with their case.

In a collaborative effort, PA Post and Spotlight PA reached out to nearly two dozen inmates initially identified by the department as eligible for reprieve, along with their family members, to see where they stood in the process. Some said they were still waiting for a meeting with the Pennsylvania Parole Board — whose sign-off is necessary for release — while others were unaware they were identified as eligible until contacted by the news outlets.

Others have been approved but are still awaiting release.

George Scantling, a prisoner at SCI Houtzdale, has been waiting for close to a month to be released after getting his “green sheet” — an official decision granting parole. He meets all the qualifications listed in the governor’s order: Scantling is 59, has diabetes and high blood pressure, is serving time for a nonviolent drug crime, and has no prior violent convictions.

“Everything for him fits the criteria,” said Sherah Freeman, a friend who helped pay off Scantlin’s outstanding prison fees, one of the conditions for early release. She said she also set up and paid $400 for a room for him in West Philadelphia.

“Why are they taking so long to get him out of there?” Freeman asked. “He’s got a job lined up. Once he gets out, he’ll be able to work. What’s the reason?”

Robert Geiman Jr., who is imprisoned in SCI Laurel Highlands, said the parole board signed off on his release, but he’s still waiting for approval from the department’s reentry coordinator.

Wolf also must sign off on each reprieve, which Geiman was told did not happen in his case. A spokesperson for Wolf referred a request for comment to the Department of Corrections, which did not address the question in its response.

“Turned out to be a joke,” Geiman wrote over the prison’s messaging system. “Something don’t add up.”

In March, the Department of Corrections estimated that up to 12,000 inmates would need to be released in order to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. Officials said they sent a list of about that many names to the Office of Victim Advocate, which sent back a list of more than 10,000 people who did not have a victim registered with their office.

After a stalemate in the legislature, with Republicans who control both chambers offering a bill that limited releases to 450 people, Wolf signed an executive order establishing temporary reprieves.

The list of criteria, however, limited the program to 1,248 inmates, close to 4% of the state’s inmate population. After the department did a second pass on the list of eligible people, officials reduced the number to 851.

Corrections Secretary John Wetzel told reporters last month that uncertainty around whether inmates will have to return to prison had been a “limiting factor.” Wolf’s order states the reprieves are temporary, though Wetzel said the department is searching for an option that would allow people who are successful on the outside to stay out of prison.

Of the inmates identified as eligible, 191 were close to being paroled, according to department data. An additional 245 needed to complete “programming needs,” like a parenting class or Alcoholics Anonymous, before they could be considered for parole.

“The reprieve process has gone a little more slowly than we thought,” Wolf said at a news conference last Friday. “But I think we have to take that in the context of the overall major reduction in the prison population.”

State officials faced intense pressure to reduce prison populations in the early weeks of the coronavirus outbreak, prioritizing those whose releases were largely uncontroversial for the sake of expediency, said Claire Shubik-Richards, executive director of the Pennsylvania Prison Society.

While that approach led to an initial surge in reprieves in the days after Wolf’s order, the flow of releases has slowed dramatically in the weeks since. More than two-thirds of coronavirus-related reprieves were granted between April 14 and 21, state data show.

“It hasn’t lived up to what the department, and certainly those of us in the advocate community, saw as its potential,” Shubik-Richards said. “It hasn't. There's uniform agreement on that.”

But the process hasn’t been a loss, she said. Finding consensus on dozens of releases was “tremendous given how fractured and contentious the criminal justice stakeholders are in Pennsylvania.”

Defense attorneys argue that the list of exclusions was too broad and didn’t include parole violators who were serving time for technical violations, such as drinking or leaving home while on supervision.

And with a look-back clause requiring inmates to not have a violent crime in the last decade (a requirement that even Wetzel said was “tough” to meet), the list of eligible inmates got even shorter.

Peter E. Kratsa, president of the Pennsylvania Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, said the exclusions for eligibility were too cumbersome, saying that some crimes included in the list arguably don’t have a victim, like pickpocketing.

“You’re really casting a wide exclusionary net,” he said. “While this looks really good in the intentions in it, in practice how many inmates does this really effect?”

Sean Damon, organizing director at Amistad Law Project, a Philadelphia-based nonprofit, said prosecutors and the victim advocate held disproportionate sway in the reprieve process, which ultimately led to fewer people safely released from prison.

He pointed to SCI Huntingdon, which as of Thursday had fewer reprieves (one) than inmate deaths (five), according to state data.

“I think that is pretty damning, and it really shows the need for us to rethink how we do criminal justice reform in Pennsylvania,” he said.

But both the Pennsylvania District Attorneys Association and the Office of Victim Advocate said their involvement isn’t the reason why only 159 people have been approved for a reprieve.

“We weren’t the barrier here,” said Jennifer Storm, the victim advocate.

Storm said her office followed the letter of the governor’s order, which was to identify victims, and didn’t have any say beyond that. She said she doesn’t know why so few people have been released.

“There should be more," Storm said.

To keep the coronavirus from spreading widely in state prisons, Wetzel in late March put the system on lockdown, suspending in-person visits and limiting inmates’ movements. That step helped the department avoid a worst-case scenario, with 259 inmates total testing positive for COVID-19 as of Thursday. Nine incarcerated people have died — five at Huntingdon and four at SCI Phoenix.

The department is now relaxing these efforts in coordination with Wolf’s tiered reopening system, though the exact timeline remains unclear.

It’s also still unknown when Wolf will end the state’s disaster emergency — triggering the end of the reprieves — or if the department will find a way to allow some inmates to stay out of prison.

The prospect of returning may be why some eligible inmates — 16 total — declined to participate in the program. But for the inmates who are ready to go home, waiting to hear about their next steps feels like a cruel tease.

“Many people here including myself have been left in the dark,” said Donald Fickles Jr., an inmate held at SCI Laurel Highlands who was never told about his eligibility. “This makes me feel the same way I’ve always felt about our system, that they don’t have our best interest in mind or our safety. I’ve always felt they are the bad guys.”

100% ESSENTIAL: Spotlight PA relies on funding from foundations and readers like you who are committed to accountability journalism that gets results. If you value this reporting, please give a gift today at spotlightpa.org/donate.