Letter to a 60-year-old male with HCC

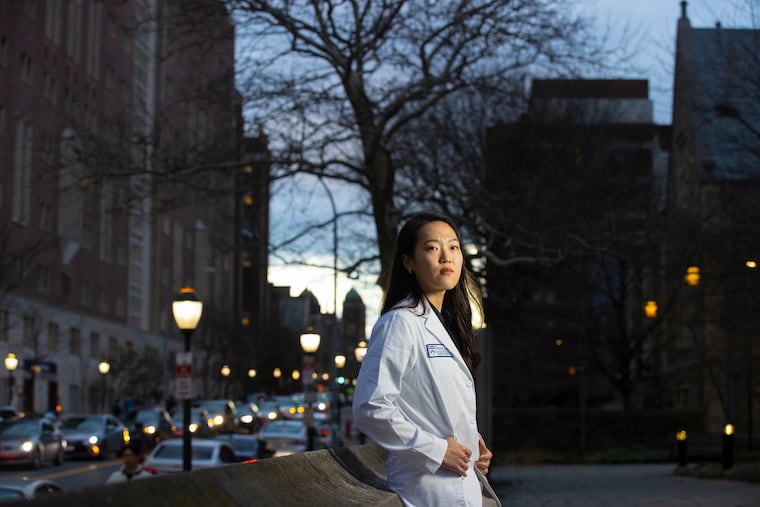

A Penn medical student shares how her father's death changed her perspective on the doctor-patient relationship and the type of doctor she wants to be.

Rebekah Chun is a second-year medical student at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and co-editor-in-chief of the student magazine Appendx. In this personal essay, she writes how her father’s death shaped her medical training and approach to becoming a physician.

Over a year ago, you came to the ER with severe stomach pain, leg swelling, and unintentional weight loss. Until now, you’d had the appearance of perfect health.

Labs showed you were positive for hepatitis B, and a CT scan found a liver lesion had spread to your blood vessels. They diagnosed you with stage 3 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) — more commonly known as liver cancer.

From your ICU bed, you watched through a video livestream as I walked across the stage during my white coat ceremony in September 2021, marking the beginning of my medical career. And you heard me say, “My fun fact is that my Korean name means grace flowing like a river, and I want to thank my parents for giving me that name.”

In October, I glared at the murkiness of the Schuylkill River as you told me how nauseous the radiation and immunotherapy made you feel.

In November, when you told me the cancer had metastasized to your lungs, I crouched down and wept on the kitchen floor in an apartment you had helped me move into just a few months before. I still have 20 pounds of brown rice you carried from H-Mart to my kitchen cabinet.

On several December days, I shared the delights of my life with you. When I told you about a sunrise walk with a friend and a trip to see The Nutcracker, you said you felt inspired and wanted to stroll around the backyard. It was the first home you had ever owned. You dug a fire pit, and nursed the scrawny persimmon and fig tree saplings, hoping to protect them from greedy deer.

Our last days together

The last day of your life coincided with the last day of my exams before winter break. In the morning, my learning teammates and I tugged on the neck tendons of cadavers for our last anatomy exam. We dug our fingers into the facial muscles and nasal septum of hemisected heads to identify which cranial nerve defect would play a role in the structures our instructors had tagged.

After time was up, we tossed our formaldehyde-splattered scrubs into a bin and catapulted out of the lab into winter break. I was so excited to go home and celebrate your 60th birthday with you.

At noon, I turned on my phone and saw missed notifications. You’d been rushed to the hospital for emergency care. I double-masked for the six-hour train ride to Charlottesville, Va., to be by your bedside.

I imagined the technical and impersonal way they talked about you, instead of to you during rounds: “A 60-year-old male with HBV-induced HCC presented to the ED last night with dizziness, abdominal pain, and ascites [fluid in the abdomen]. ... Imaging revealed a ruptured branch of his left hepatic artery. …”

Interventional radiologists controlled the initial bleeding, but the electrolyte imbalance from hemorrhage contributed to an irregular heart rhythm. Medical staff revived you with CPR, but couldn’t stop the bleeding. You were put on dialysis until doctors could discuss next steps with your family.

When I made it to your bedside around 8 p.m., your neck was what I noticed first. Multiple IV tubes crawled up next to your jaw — a central line, as I later learned — to meet various bags of fluids suspended on a pole. Your lips were blue and your nose was rimmed with dried blood. Still, you greeted me with a smile.

“Have you eaten?” you asked. “Where are you staying for the night?”

I put on a pale-yellow isolation gown and blue nitrile gloves and placed my hand on your left leg — your arms and other leg were already taken by Mom and my two sisters. A few minutes later, a resident on call walked in and told us there were no options other than palliative care. It was a “very bloody cancer,” the resident said. You were on life support, which stabilized you enough to see all of us for a last goodbye.

I asked the resident which of your blood vessels had ruptured, as if the answer would somehow help. It was the liver’s main artery.

At 10 p.m. after we listened to your last words, your ICU nurse asked whether you would like something for anxiety in addition to morphine. You responded, “No, thank you. My daughters are my anti-anxiety medicine.”

You were strangely lucid and calm for someone bleeding to death.

There is a dimple on my left ear that takes after yours, Appa. I remember caressing it as we waited for your blood pressure to drop. When your eyes were half-open with a blood pressure of 40/20, did you say my name and mouth “I love you” on your last breath?

My vow to be a kindhearted doctor

It’s been a year since you died. During that time I’ve been learning about what you suffered through as a patient. Shortly after I returned to school following your funeral last January, I studied the stages of hemorrhagic shock. I couldn’t help but imagine what your scarred liver must have looked like as I confronted pathology carts with thick, noxious slices of liver with “mets” — a flippant shorthand for tumor metastasis. Images of “portal hypertension” and the “clotting cascade” chased me in my dreams.

When I was shadowing in a pediatric ICU one day, an attending joked to a fellow, “You still feel emotions when you’re having end-of-life conversations? We will beat that out of you soon enough.” I found myself tempted by the offer. I didn’t want to keep being overwhelmed by the sharp pangs of losing you. And to cope with my grief, I pathologized you and reduced you to your disease.

And yet, as I progress through my medical training, I promise to fight the urge to reduce you and my patients to a disease and deaden my heart.

We didn’t get a chance to talk about this, but you probably read this line from The Four Loves by C.S. Lewis: “To love at all is to be vulnerable. ... If you want to make sure of keeping it intact, you must give your heart to no one. ... It will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable.”

Would I have traded never being heartbroken in exchange for never knowing you and loving you? No.

And I will treat my patients and their families the same. I will risk the devastation I may experience by entering their stories. I will ask about their roots and attempt to see them as fathers and daughters, beloved friends and colleagues.

I wish your care team had known you the way we did: How you croaked out a joke even at your last hour. How you wrote a secret blog in four languages to prepare us for your passing. It featured logistics of your medical bills and utility accounts, instructions on how to take care of a septic tank, list of phone numbers and addresses of elementary school friends whom I barely remembered, musings on theology and life, and so much more.

Appa — you weren’t a perfect man, but you were a loving father. Thank you for leaving everything behind in Korea in the hopes of building a better future for your daughters, even as I wished you had not suffered through the indignities of being an outsider.

Thank you for teaching me how love can take the form of a bag of Asian pears you had picked out for Thanksgiving from Kroger, where you had hobbled to with a black walking cane.

Thank you for teaching me how silence can feel like a warm embrace.

I wish I could hug you, but this letter will do for now.