Pink noise, a popular sleep aid, could disrupt sleep quality, Penn study suggests

Often used to mask unwanted sounds at night, pink noise was found to reduce REM sleep in a recent Penn sleep lab study.

Marketed as a ticket to deeper sleep, the soft hum of pink noise has become part of millions’ nightly routines.

However, its use may come at the cost of sleep quality, a University of Pennsylvania study suggests.

Published this month in the medical journal Sleep, the study found that the presence of pink noise at night reduced REM sleep — the stage when most vivid dreams occur and memory, emotional regulation, and learning are supported. This was based on a sample size of 25 healthy adults assessed over seven days in a sleep lab.

To Mathias Basner, a Penn professor of psychiatry and lead author on the study, it’s evidence that background noise may not be risk-free.

“The negative consequences of the pink noise far outweigh the positive ones that we saw,” he said.

Pink noise vs. white noise

Pink noise is what’s called a “broadband noise,” meaning sounds made up of a wide range of frequencies. The most well-known example of this, white noise, is considered the sound equivalent of the color white, which contains all colors combined.

Pink, brown, and other colored noises differ based on the frequencies they boost.

Pink noise, for example, emphasizes lower frequencies — making it sound similar to steady rainfall or ocean waves. It’s often used for sleep, although uses for focus and tinnitus have also been reported.

These types of background noise can mask unwanted sounds — an appealing quality in an increasingly noisy world.

Since the first white noise machine for sleep was released in the 1960s, hundreds of variations have spawned. Today, 10-hour videos of pink noise, which is often preferred over white noise for sleep due to its softer sound, pick up millions of views on YouTube.

“So many people are using it, and it’s really indiscriminate use,” Basner said.

Putting pink noise to the test

Having studied the effects of noise his whole career, Basner was surprised to learn several years ago that some people used it as a sleep aid.

That led him down a rabbit hole of research, where he found dozens of studies assessing the effects of broadband noise on sleep. However, most of them were considered to be low quality — sample sizes were small and the assessments were usually subjective.

“We don’t know whether it’s working, whether it’s harmful or not,” he said.

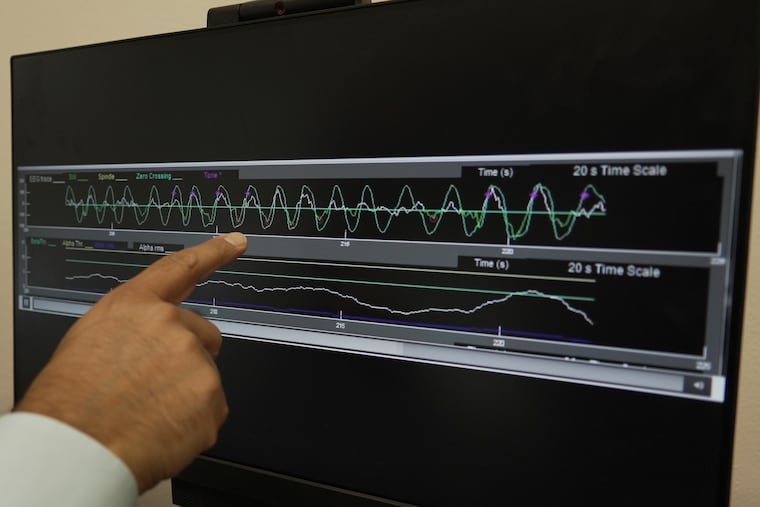

He designed his study to occur in the hypercontrolled environment of a sleep lab at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, where participants were measured using polysomnography, a test that looks at brain waves, eye movements, and muscle tone.

This allowed his team to differentiate sleep stages and figure out what was happening biologically as participants were exposed to a variety of conditions: no noise, environmental noise, pink noise, pink noise and environmental noise combined, or environmental noise with ear plugs.

Each night, the 25 participants, comprised of 18 women and seven men, were given an eight-hour window to sleep. (Lights were out at 11 p.m. and back on at 7 a.m.)

His team found that environmental noise — which ranged from the sound of a helicopter to a sonic boom — led to a 23.4-minute decrease in stage 3 sleep. This so-called deep sleep phase where recovery occurs is important for physical repair and immune function, as well as memory.

And while pink noise didn’t affect deep sleep, it was associated with an average decrease of 18.6 minutes in REM sleep.

“REM sleep is extremely important for a lot of things like memory consolidation, emotion regulation, brain plasticity, and neurodevelopment,” Basner said.

Though the study didn’t look at children, he cautioned that babies spend around half of their time sleeping in REM, compared to a quarter in adults.

Based on his findings, he would discourage parents from using broadband noise machines in the bedrooms of newborns.

For adults who don’t want to forgo the noise, he would recommend using the lowest volume and setting a timer so it eventually turns off.

However, the best option would be to use foam ear plugs, he said. When paired with environmental noise in the study, they were able to block out noise and recover 72% of the deep sleep time that had been lost — although they did start losing effectiveness at higher noise levels, around 65 decibels.

“You didn’t get the REM sleep reduction because they didn’t play anything back,” Basner said.

A limitation of the study is that it had a relatively small sample size comprised of younger, healthy people without sleep disorders or hearing loss. It also only looked at the short-term effects of pink noise, and was conducted in a lab setting, versus the participants’ homes.

In the future, Basner hopes to study the long-term effects of pink noise on sleep, as well as test other types of broadband noise.

“We need to do the proper research to make sure that it is actually, at least, not harmful,” he said.