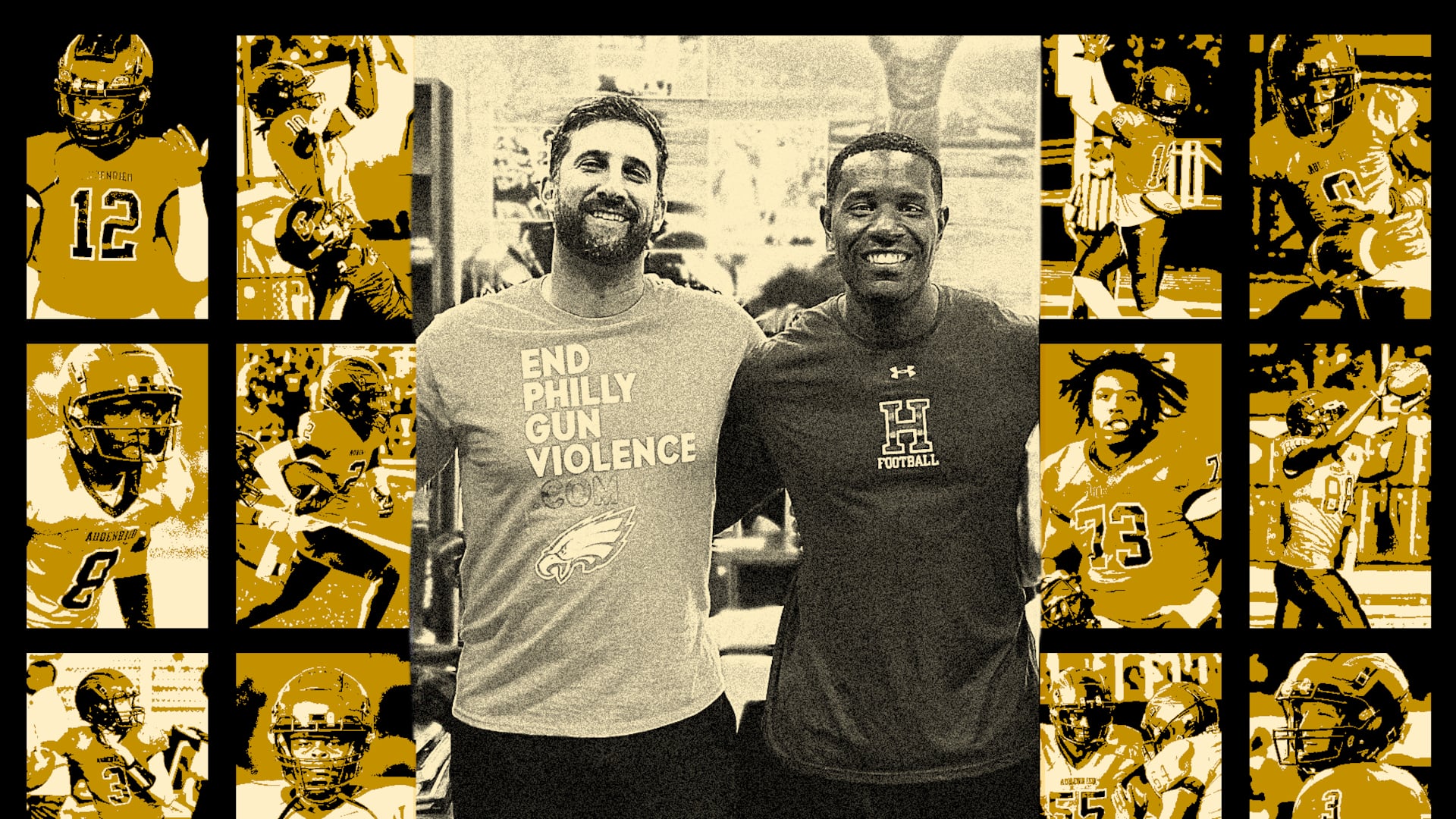

Nick Sirianni was his mentor. Now, Roy-Al Edwards is building a new football program.

This year marks the first time that Universal Audenried Charter is fielding a varsity football team, and with Edwards at the helm, he’s using core values that he learned from Sirianni.

Roy-Al Edwards had little interest in Indiana University of Pennsylvania when he first started looking at colleges. The star wide receiver from Media had earned offers to walk on at big, Division I schools, like Penn State and Temple, and was recruited by Vanderbilt University.

IUP, by contrast, was a smaller program, in a tiny town, 56 miles northeast of Pittsburgh. Edwards was only willing to move far from home if it meant going to a powerhouse. A Division II school that produced fewer than a dozen NFL players did not seem worth the effort.

Then he met Nick Sirianni. It was January 2006, and the two sat together in an office inside Strath Haven High School. Sirianni, then a wide receivers coach, asked Edwards about his goals. He also talked about his own — specifically, of wanting to one day lead an NFL team.

Sirianni told the young receiver that he’d do everything he could to make the transition to Western Pennsylvania easy. A few weeks later, after Edwards committed to IUP, the coach showed him that he meant it.

He organized a dinner at a Caribbean restaurant because Edwards was Jamaican. Sirianni drove 260 miles from Indiana, Pa., to Bahama Breeze in King of Prussia to introduce the incoming freshman to Ken Witter, an IUP wide receiver from Norristown, who would become Edwards’ mentor.

“Before I stepped on campus, I was already home,” Edwards said, “because of how [Sirianni] made me feel.”

Over two seasons together at IUP, the wide receiver built a bond with his position coach. He listened as Sirianni extolled his core values — connect, compete, accountability, football IQ, and fundamentals. He watched as he showed his players that he cared about them, not only as athletes, but as people.

Sirianni left IUP in 2009 for a job with the Kansas City Chiefs. After stops with the San Diego Chargers and Indianapolis Colts, he realized his dream in 2021, when he was named head coach of the Eagles.

Before I stepped on campus, I was already home, because of how [Sirianni] made me feel.

Through it all, he remained in touch with Edwards. Now, they’re reunited in South Philadelphia, where Edwards is at the helm of a new football program at Universal Audenried Charter School.

For years, the school was plagued by poor grades, low graduation rates, and so many violent episodes that it was given a menacing nickname: “The Prison on the Hill.”

In 2011-12, these problems reached a breaking point when Audenried was put on a list of the most dangerous schools in Philadelphia.

Edwards has been at the helm of the football program for just one season, but he and the team have already brought about real, positive change. And the coach has drawn from Sirianni’s culture to do that.

In 2023, on a visit to the NovaCare Complex, Edwards talked with Sirianni about the core values he once used at IUP.

“He said, ‘Make sure you implement these,’” Edwards said. “And I was like, ‘I’m just going to steal them, bro.’ Our core values are the Eagles’ core values.”

Coaching with (tough) love

Edwards was raised by his grandmother, Myrtle Terrell, in Media. His father wasn’t around, and his mother wasn’t able to be as involved as she wanted to be.

It was a challenging environment, but he found success at Strath Haven, where he was both an honor student and an excellent athlete. In 2005, Edwards helped lead his school to a district championship. In 2007, he was named to the All-Delco first team.

By the time the wide receiver arrived at IUP, in the summer of 2007, he had gotten, by his own admission, “a pretty big head.” Although his commitment to Vanderbilt had fallen through, he still felt — and acted — as if he was worthy of a prestigious Division I program.

The freshman did not adjust well. He was late to weightlifting sessions; sometimes he skipped them entirely. He would fall asleep watching film. Sirianni took note, and quickly quashed the notion that Edwards was above doing hard work.

“He held me accountable,” Edwards said. “And it’s just funny, because that’s one of his core values — accountability. He had me doing wall pushes for long periods of time. He’d make me stand up and watch film. It was every little thing.”

To Sirianni, this was a gesture of love, albeit tough love. There were other ways he showed he cared. Even as early as 2007, the coach would call Edwards into his office to watch film together.

I don’t know too many college coaches who do that. You’re focusing on the players who are going to play in the game, not the redshirt freshman who is on the scout team. But he would coach me up as if I was a starter.”

“I don’t know too many college coaches who do that,” Edwards said. “You’re focusing on the players who are going to play in the game, not the redshirt freshman who is on the scout team. But he would coach me up as if I was a starter.”

In the fall of 2008, Edwards blew out his knee on a kickoff return. He suffered a torn ACL, MCL, and meniscus. The wide receiver was devastated. His season had gotten off to a promising start, only to reach an abrupt end. His family was hundreds of miles away.

So, Sirianni decided to step up. After the game, he helped Edwards into his old, two-door Pontiac Grand Prix. He drove him to a local hospital for an MRI, and then drove him back a few days later to undergo surgery.

For the next week, Edwards stayed with Sirianni and his roommates in their apartment. The coach would check in on him throughout the day, making sure he was hydrating and eating right.

“We had a spare spot on our couch,” Sirianni said. “You can talk about relationships all you want, but if there’s no action to it, it really means nothing. This was just something Roy-Al needed, and I was happy to help him out any way I could.”

Sirianni had endured a similar experience in 2001, when he suffered a leg injury while playing wide receiver at Mount Union. Like Edwards, Sirianni had to undergo surgery. He stayed in the hospital for about a week, and his college coach, Larry Kehres, visited him frequently.

Sirianni later called it “the most difficult thing” he had ever gone through. But he never forgot Kehres’ gesture.

“I was so invested in Mount Union football,” Sirianni said. “I wanted, desperately, to be a starter. I just think I noticed that I wanted to go even harder than I thought I could [after that].

“You may think to yourself, ‘I’m going to go as hard as I possibly can at all times,’ but there’s ultimately one thing that helps you go a little bit harder. And that’s love. Love will help you go further.”

In 2009, Sirianni landed his first NFL job, working as an offensive quality control coach for the Chiefs. It was a major jump from IUP, bringing him one step closer to his dream of becoming an NFL head coach.

For Edwards, it was bittersweet.

“I was like, ‘Man, I’m never going to get a coach like him ever again,’” Edwards said. “Nothing against the coaches I had once he left, but they weren’t Coach Sirianni.”

Sirianni and Edwards were in different time zones, and on different schedules, but they still stayed in touch after he left. Sirianni was usually the one to reach out. He would ask Edwards how he was doing and how the team performed that week.

As Sirianni climbed the NFL coaching ranks, the texts and phone calls became less frequent. But the coach and his pupil always reconnected. And despite Edwards’ disappointment about Sirianni leaving IUP, he always had an unwavering belief in his coach.

Sirianni’s first season in Philadelphia, 2021, was bumpy. Fans criticized him for looking nervous in his introductory news conference. Later that year, when the Eagles were 2-5, the coach showed his team a picture of a flower, as a metaphor for growing roots that would soon bloom.

Sports talk radio mocked him at length. Fans started to call for his job.

Edwards’ friends and relatives in the Philadelphia area peppered him with questions about the new head coach. Even his barber had concerns.

“He’d be like, ‘You sure we’re good with this guy? I don’t know about this guy,’” Edwards recalled. “And I would always tell him, ‘Listen, he is going to win us a Super Bowl.’ I knew we were in good hands.”

After graduating from IUP in 2012, Edwards followed in Sirianni’s footsteps and transitioned into coaching. He spent six years as an assistant football coach at Glen Mills School, then five years in a similar role at the Haverford School.

While Edwards was at Haverford, in 2023, Sirianni invited him to offseason organized team activities, or OTAs. They sat in his office at the NovaCare Complex and looked out the window as Eagles players walked onto the field.

“He was like, ‘You have access to everything that I have access to. So, if you ever want film, and this or that, let me know,’” Edwards said. “And I’m just sitting here thinking, ‘I watch these guys play on Sundays.’

“I’m like, ‘Coach, you really did what we talked about in 2006. It’s crazy.’”

‘He’s saving their lives’

In February, about a week after Sirianni led the Eagles to their second Super Bowl championship, Edwards called him on FaceTime.

The coach was at a charity event and stepped outside. They reflected on how far they’d come.

“I talked about it, you talked about it, and the dream came true,” Edwards said to his former coach.

Sirianni asked what he was up to, and Edwards told him about the job at Audenried. He had worked at the school as the dean of students since 2022, but had recently decided to start a football program, in 2024.

In the past, Audenried’s players had the option to play for South Philadelphia High’s varsity team, but only a few participated. The school had never had a program of its own. This was due to a confluence of factors. Student enrollment was low. There wasn’t a lot of funding to go around. The neighborhood — in Grays Ferry — was plagued by poverty and crime.

Rather than being safe havens, schools were the sites of some of the most brutal attacks. A 2011 investigation by The Inquirer found that among Philadelphia’s 32 neighborhood high schools — including Audenried — the rate of violence had increased by 17% between 2005 and 2010.

“We were on the persistently dangerous list [in 2012],” said Audenried’s principal, Josh Anderson. “This was a pretty violent school when I first got here. There was a period of time when 24th Street and 27th Street were just pretty much killing each other. And so that was a concern, because safety is always at the forefront of my mind.

“I feel like the school community, as well as the community in Grays Ferry, has made a collective decision that they’re going to make Audenried a peaceful place for students.”

The Philadelphia Public League mandates that all school athletic programs start their first season on the junior varsity level, so Audenried fielded a JV team in 2024. It ran into obstacles almost immediately. The players practiced at Smith Playground, which had a turf field but was 20 blocks away.

Later that season, they moved to James Finnegan Playground, a site a few blocks closer, but one that barely had any grass.

“It was like we were playing in dirt,” Edwards said. “The field was horrible.”

Despite the lack of resources, there was genuine excitement around the team. Audenried went 6-3. Players felt like they were building something, and quickly developed a special bond with their coach.

Like Sirianni, Edwards worked hard to show his team that he cared. He brought in guest speakers who had played college football. He took the players on trips to colleges. He found a nonprofit that donated equipment — cleats, shoulder pads — and offered to drive the players to Planet Fitness over the summer.

But his investment in them wasn’t just as athletes. As dean of students, Edwards also kept a close eye on their grades. It has helped him hold his players accountable.

“I can go talk to their teachers,” Edwards said. “I can make sure they’re getting the support they need from the counselors. For kids who have [individualized education programs], I can be in the mix of everything.

“I call them my boys. They’re my boys now. I treat them like they’re my own sons.”

The enthusiasm for the football program carried over to 2025, Audenried’s first varsity season. It had a new field to practice on, less than a mile away — the recently renovated Vare Recreation Center — and began playing home games at the South Philadelphia Super Site.

Forty-six players signed up. A few transferred in from other schools, in large part because they wanted to work with Edwards.

Dmayne Austin, a sophomore running back, spent the first half of his freshman year at Father Judge. His mother, Dannyelle, became concerned when he started missing practices.

This was uncharacteristic for Dmayne, she said. He’d played football since he was 5 and had always been dedicated. He had heard good things about Audenried through a few friends who went to school there, so he and his mother took a tour.

I could really see that he really believed in us. I actually felt good. It put a smile on my face.

After meeting Edwards, Dmayne was sold.

“I could really see that he really believed in us,” he said. “I actually felt good. It put a smile on my face.”

Dante Bundick, a junior wide receiver, had a similar experience. He, too, began playing football at age 5, but had recently lost motivation after joining the team at Bartram High School. His mother, Lakisha Doe, could tell something was off.

“Dante was saying, ‘I don’t want to play football no more,’” Doe said. “‘I give it up. I’m just tired. I don’t want to do weight room.’

“He was missing practice. And that was definitely odd for him, because even as a freshman, he started. He’s a good football player.”

They met with Edwards in May, and Bundick transferred over. He hasn’t missed a practice since. In fact, he has forgone opportunities to go on vacation with his family so he could be with his team.

Doe says that Edwards isn’t just teaching his players football. He’s also teaching them how to be men.

“This is a grown man who takes care of his family,” she said. “He brings his family with him [to games].

“I am blessed to have him leading my child.”

In the spirit of connection — another Sirianni core value — Edwards has started to organize team dinners. Different parents provide meals every week, the night before games.

The parents and athletes are all on an app where Edwards will post workout plans, diet plans, and other pieces of advice.

His words of motivation have been helpful lately, as Audenried has started its season with a 1-2 record. In its first game, against Cardinal O’Hara, Edwards’ team lost, 49-0. In its second, against Chichester, it lost, 36-16.

Audenried won its third game, against Vaux Big Picture, 26-6.

After the game against Chichester, Ashley Reese, mother of wide receiver Steven Stones, walked down to the field. She got within earshot of the huddle and listened to Edwards’ message.

She was encouraged by what she heard.

“He told them to really think about what they could have done better,” she said. “But he also said, ‘It’s not all on you. It’s on me, too. I’m going to make improvements and I’m going to make changes. And I’m going to figure out how I can support you better.’

“That’s what it’s all about.”

These parents know how hard it is to reach the NFL. They know how hard it is to earn a spot on a competitive Division I program. But they also know that Audenried football is about more than that.

“It keeps these kids out of the streets,” Doe said. “Coach Ed is keeping them safe. He’s saving their lives.”

An Eagles-inspired foundation

Edwards hasn’t reached out to Sirianni this season, but he knows that if he needs to, he can. He believes that he and the Eagles coach are in the same place, at the same time, for a reason — just as they were back in 2006.

There is a symmetry to all of this. A few miles from Lincoln Financial Field, where Sirianni is helping the Eagles defend their title, his old wide receiver is building a program from the ground up, in a pocket of Grays Ferry.

They have a reputation to change. They have obstacles in their way. The results aren’t there yet.

But their foundation is strong — and it stems from one man.

“I’m honored,” Sirianni said. “The way Roy-Al coaches, and helps these kids, it almost feels like you’re helping a lot of people, even if you’re just helping Roy-Al. I’m a little out of words. But I am really honored.”