From The Inquirer archives: An athlete excels in wheelchair track and field

This article originally appeared in The Inquirer on July 1. 1984.

This article originally appeared in The Inquirer on July 1, 1984.

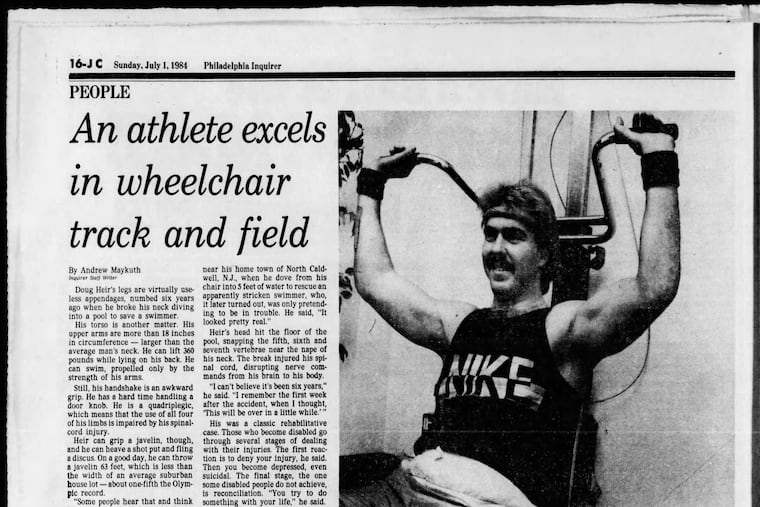

Doug Heir’s legs are virtually useless appendages, numbed six years ago when he broke his neck diving into a pool to save a swimmer.

His torso is another matter. His upper arms are more than 18 inches in circumference — larger than the average man’s neck. He can lift 360 pounds while lying on his back. He can swim, propelled only by the strength of his arms.

Still, his handshake is an awkward grip. He has a hard time handling a door knob. He is a quadriplegic, which means that the use of all four of his limbs is impaired by his spinal-cord injury.

Heir can grip a javelin, though, and he can heave a shot put and fling a discus. On a good day, he can throw a javelin 63 feet, which is less than the width of an average suburban house lot — about one-fifth the Olympic record.

“Some people hear that and think it’s not too far,” the third-year Rutgers University law student said in his Cherry Hill apartment recently. ‘‘But if they sat in a chair and tried it, I doubt they could do it.”

As a matter of fact, 63 feet is the world's record for the javelin throw by a wheelchair athlete. Heir set the record two years ago in the International Wheelchair Games in England.

Later this month, at the Stoke Mandeville Games in England, Heir will try to break his mark in the javelin throw. But another event will assume a larger importance for Heir: the pentathlon, a combination of five track and field events.

At the end of May, Heir won the pentathlon in the 28th National Wheelchair Games in Tennessee, becoming recognized as the best all-around wheelchair athlete in the United States. The winner of the Stoke Mandeville pentathlon will be considered the best wheelchair athlete in the world.

These accomplishments speak well for a man whose most prominent athletic achievement before his accident was to secure a position as starting defensive tackle on the football team at Alfred University in New York.

This is his story of triumph over adversity, or, about how Doug Heir's face nearly appeared on your grocery shelves on a box of Wheaties.

Six years ago, Heir was an 18-year-old college freshman, 6-foot-3, who happened to be in good physical shape.

On June 18, 1978, he was working as a lifeguard at a swimming pool near his home town of North Caldwell, N.J., when he dove from his chair into five feet of water to rescue an apparently stricken swimmer, who, it later turned out, was only pretending to be in trouble. He said, “It looked pretty real.”

Heir’s head hit the floor of the pool, snapping the fifth, sixth, and seventh vertebrae near the nape of his neck. The break injured his spinal cord, disrupting nerve commands from his brain to his body.

“I can’t believe it’s been six years,” he said. “I remember the first week after the accident, when I thought, ‘This will be over in a little while.’”

His was a classic rehabilitative case. Those who become disabled go through several stages of dealing with their injuries. The first reaction is to deny your injury, he said. Then you become depressed, even suicidal. The final stage, the one some disabled people do not achieve, is reconciliation. "You try to do something with your life," he said.

“In life, there are 10,000 things you can do, and now you can’t do 2,000 of them,” he said, quoting a therapist who helped him through his rehabilitation. “You can cry about the 2,000 you can’t do, or you can go for the 8,000 you can.”

He began creating a new self-image, and he began getting used to a new perspective on life, on a world viewed from a chair three feet off the ground. It was a world fraught with obstacles he had never before considered: curbs and stairs and prejudices.

After eight months of rehabilitation, he entered Ramapo College of New Jersey, where he was introduced to wheelchair sports. “There were a lot of people out there, a lot of spinal-cord injuries. And the competition was tough.”

One year to the day after his injury, he was in his first national wheelchair competition.

Field events for wheelchair athletes are slightly different than those for other athletes. A javelin thrower, for example, will take a running start before throwing. A shot-put thrower will spin in a circle several times before heaving the shot to build up momentum. The wheelchair athlete, however, throws everything from a stationary, sitting position.

Consequently, the distances achieved in wheelchair field events are much shorter than for regular athletes. “I tend to be defensive,” Heir said, ‘‘because I used to do track. But I’m stronger now than I was then.”

His distances in the field events have been outstanding enough to overcome his lack of speed in the 100-meter and 800-meter races. At the May nationals, he won a gold in the pentathlon, as well as golds in the shot-put and discus events. He also won a bronze medal in the javelin.

Still, Heir is no slouch as a racer. He now is training to increase his endurance for the Stoke Mandeville Games, where more than 2,000 athletes from about 90 countries are expected to compete from July 21 to Aug. 1. The pentathlon is the most prominent event of the games. He is also raising funds for the trip.

Winning the pentathlon would be his crowning athletic achievement, he said. It would be enough of an honor to overcome his disappointment at narrowly losing a contest last winter — not a physical race, but a contest to determine which amateur athlete would appear on a box of Wheaties.

George Murray, a wheelchair racer, was chosen as the symbol for the “Breakfast of Champions.” Heir received a runner-up trophy. His friends at Rutgers Law School ended up with $150 worth of the breakfast cereal, from which they had removed the boxtops for Heir’s contest entry.

“I don’t want to brag or anything . . .” he said, stopping his sentence short. “Ah, well, maybe some day.”

As a matter of fact, the New Jersey Wheelers, Heir’s wheelchair team, recently entered him in the Search for Wheaties Contest II.

Editor’s note: Six months after this story was published, General Mills selected Doug Heir to appear on 3 million boxes of Wheaties cereal. He went on to win more than 300 gold medals in international competitions. Heir also earned his law degree and pursued a career as a motivational speaker and advocate for people with special needs.