From The Inquirer archives: Epileptic man puts the dusty trail behind after a cross-country publicity walk

This article originally appeared in The Inquirer on Aug. 10, 1983.

This article originally appeared in The Inquirer on Aug. 10, 1983.

With her arms outstretched, 4-year-old Desiree Warren ran to greet her father when he came home yesterday.

The little girl with short blond hair pushed her way through a crowd of more than 100 people, including Mayor Bill Green III, who had gathered outside Graduate Hospital to welcome Patrick Warren on his return from a 3,000-mile walk across the nation to promote awareness of epilepsy.

Warren, 36, a South Philadelphian who runs a roofing company with his brother-in-law, said he made the trip to prove that he and the more than 2 million Americans who have epilepsy, a disorder of the central nervous system, can do almost anything.

Warren averaged 25 to 35 miles a day on his trip from Los Angeles, which was sponsored in part by Graduate Hospital's Comprehensive Epilepsy Center. He wore out four pairs of walking shoes.

Rattlesnakes were the biggest problem he encountered during the 100-day trek. “Snakes like to bask in the sun,” Warren said. “I saw 25 or 30 along the highways as I walked. Three times, in Arizona, Arkansas, and New Mexico, rattlers coiled to attack. I kept my distance from them with my good old blackthorn walking stick from Ireland — I knew rattlers could only spring about four feet, the distance of my stick.”

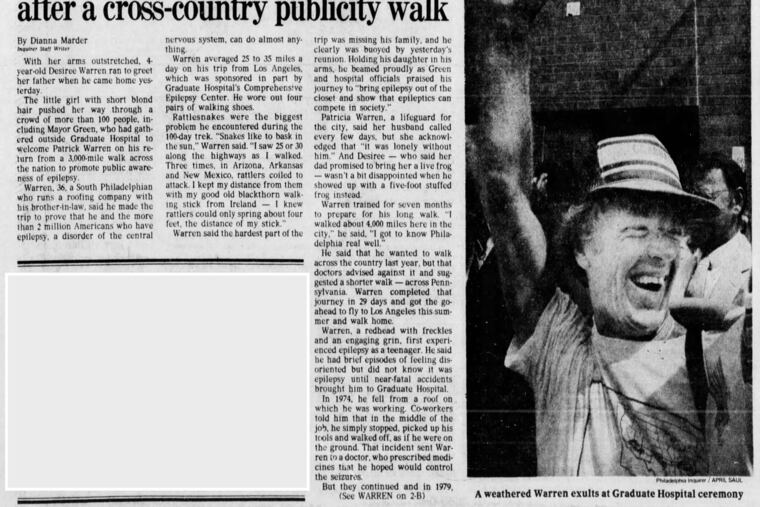

Warren said the hardest part of the trip was missing his family, and he clearly was buoyed by yesterday’s reunion. Holding his daughter in his arms, he beamed proudly as Green and hospital officials praised his journey to ‘‘bring epilepsy out of the closet and show that epileptics can compete in society.”

Patricia Warren, a lifeguard for the city, said her husband called every few days, but she acknowledged that “it was lonely without him.” And Desiree — who said her dad promised to bring her a live frog — wasn’t a bit disappointed when he showed up with a five-foot stuffed frog instead.

Warren trained for seven months to prepare for his long walk. “I walked about 4,000 miles here in the city,” he said. “I got to know Philadelphia real well.”

He said that he wanted to walk across the country last year, but that doctors advised against it and suggested a shorter walk — across Pennsylvania. Warren completed that journey in 29 days and got the go-ahead to fly to Los Angeles this summer and walk home.

Warren, a redhead with freckles and an engaging grin, first experienced epilepsy as a teenager. He said he had brief episodes of feeling disoriented but did not know it was epilepsy until near-fatal accidents brought him to Graduate Hospital.

In 1974, he fell from a roof on which he was working. Co-workers told him that in the middle of the job, he simply stopped, picked up his tools and walked off, as if he were on the ground. That incident sent Warren to a doctor, who prescribed medicines that he hoped would control the seizures.

But they continued and in 1979, Warren suffered a fractured skull in another fall from a roof. The injury brought Warren to Graduate Hospital's Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, 19th and South Streets, where his illness was finally diagnosed and brought under control. Warren's cross-country trip was his way of showing his gratitude to the hospital.

Joan Sterrett, executive director of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, said epilepsy is most often caused by head injuries suffered either at birth or during a later trauma. The injury creates scar tissue that causes electrical impulses that trigger seizures.

Only 50% of epileptics suffer the dramatic convulsions that people often associate with the illness, Sterrett said. The rest, like Warren, suffer seizures that affect only the part of the brain that has been injured. The symptoms of seizures thus are varied, making the illness difficult to diagnose. The seizure can be so short — 90 seconds at most — and so subtle that the sufferer can think he or she is going crazy, she said.

With the right balance of medications, seizures can be controlled, Sterrett said. Warren, who takes medication daily, said that he has been seizure-free for one year and that makes him eligible to regain his driver’s license — the only activity legally denied him as an epileptic. He plans to return to the roofing business, but not to rooftops.