Finding Flow: When work feels like play

I believe schools are not places where most young people have a chance of finding flow. Instead, their work is often too easy, too hard—or just irrelevant to anything they really care about.

This is the first in a two-part series on the legacy of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who died in October.

Years ago, when I was still in graduate school, I went into the lab one Saturday to retrieve a book I’d left on my desk.

The halls and offices were dark and silent. Book in hand, I hurried back to the elevator.

And then, out of nowhere, appeared the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, dressed head to toe in black and holding a book of his own in one hand, a cup of coffee in the other.

We exchanged greetings. Then I asked, “What are you doing here?”

I knew Mike (which is what everyone called him) was visiting our lab for the summer. I just didn’t expect to see him there on a perfect, sunny weekend afternoon.

“Why shouldn’t I be here?” he replied with a smile. “There’s nowhere I’d rather be.”

Mike was a wonderful exemplar of the intrinsically motivated creators he studied. For instance, when he was at my stage — still in graduate school — he followed painters into their studios. In one of his last interviews, he recalled:

I was most interested in the fact that these people would spend weeks and weeks working on a painting and they would forget everything while they were working. Then they’d finish a work of art, and instead of enjoying it — which is what you would expect from the theories of psychology…that you work in order to get something rewarding at the end. After 10 minutes or so they would put it against the wall and start a new painting. They weren’t really interested in the finished painting.

In other words, work wasn’t a means to an end. It wasn’t for a grade or praise, for money, status, or fame. The process of work was its own reward. And when working, the creator was fully immersed, just completely absorbed in the work itself — a psychological state Mike would later call flow.

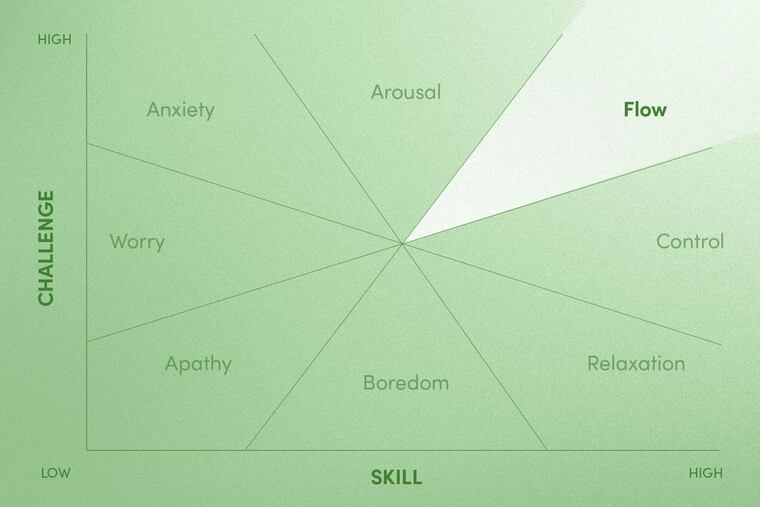

The flow state, it turns out, is relatively rare. One reason why is that when you’re in flow, you’re doing something at very high levels of both challenge and skill. You’re at the edge of what you can do but still in control. You’re not bored (too easy) or anxious (too hard). You’re not worried. And you’re not apathetic.

When I think of Mike and flow, I immediately think of how lucky he was to have work he loved so much that it was what he did when he had no other obligations. And I think of the millions of children and teenagers who, in contrast, spend so many, many hours of their lives bored, anxious, worried, or apathetic.

Like Mike, I believe schools are not places where most young people have a chance of finding flow. Instead, their work is often too easy, too hard — or just irrelevant to anything they really care about.

Try asking the young person in your life this question, which in that interview, Mike mentioned as a quick diagnostic for the flow state: “Have you ever been involved in something that attracts you so deeply that you don’t notice time passing?” One of Mike’s lifelong dreams was that schools become havens of creativity, places where young people might say with a smile, “Why shouldn’t I be here? There’s nowhere I’d rather be.”

Angela Duckworth is the founder and CEO of Character Lab and a psychology professor at the University of Pennsylvania. Sign up to receive her Tip of the Week — actionable advice about the science of character — at characterlab.org.