The little-told story of the Tuskegee weathermen

"Just as the black pilots proved that they could fly military aircraft in combat as well as the white pilots, so did the black weather personnel prove that they could perform meteorological functions as well as the white officers."

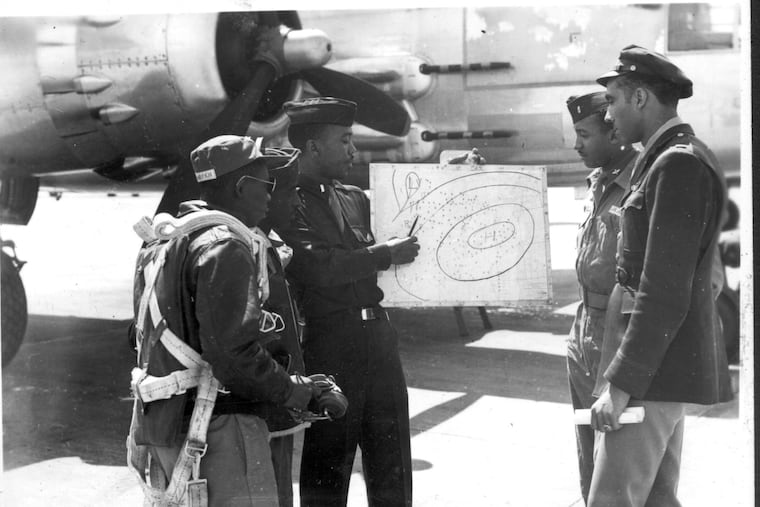

Much has been written about the Tuskegee Airmen, the first black pilots in the U.S. military, who flew their signature red-tailed P-51 Mustangs in Europe during World War II. Less remembered are the meteorologists who helped guide their historic run of missions — the Tuskegee Weather Detachment.

The first black weather officers in the Army Air Forces, they counted among their ranks such groundbreaking meteorologists as Charles Anderson, the first African American to earn a Ph.D. in meteorology, and Wallace Reed, their commander, who was the first black weather officer in the Army Air Forces.

“In retrospect, these men, like the rest of their Tuskegee peers, were pioneers,” retired Air Force historian Gerald White Jr. wrote in his history of the weather detachment. “In joining the Army and becoming weather officers, a career choice unimaginable before World War II, they met the high entry standards and successfully completed the most academically rigorous course offered by the Army in World War II, a noteworthy achievement in its own right.”

The weather detachment was a by-product of the push to enlist black aviators in the military. At the end of his second term, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was facing pressure inside the White House, from his adviser, famed educator Mary McLeod Bethune, and out on the campaign trail, from Republican presidential hopeful Wendell Willkie, who had vowed to desegregate the military in an effort to court black voters. In 1940, Roosevelt responded by allowing black pilots to join up.

Shortly thereafter, the War Department publicly announced it would form a “Negro pursuit squadron,” to be trained at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama. Flying units had to be staffed with weather officers, and because the Army was segregated, the new assembly of black aviators would be joined by a contingent of black meteorologists. In March 1942, the Tuskegee Weather Detachment was born.

At that time, there were no black meteorologists in the Weather Bureau, so the Army recruited black men with a background in science who could be trained in meteorology. Anderson, who originally wanted to be a pilot, was a good fit, having studied chemistry in college.

» READ MORE: The pilot and the professor: A Tuskegee touchdown on the Main Line

“Flight crews were out of the question because my eyesight was not good enough, so that meant that I had to do something on the ground. I could have gone into engineering but my background in math and chemistry seemed to be exactly the kind of background that they were looking for [in] meteorologists, so I applied,” he said in a 1992 interview for the American Meteorological Society Oral History Project.

Anderson went on to attend the Meteorological Aviation Cadet Program at the University of Chicago, learning alongside white students who were also preparing to join the Army Air Forces.

“It was rough. It was very rigorous, very demanding and — what should I say — very stressful, because every Monday morning you had an examination on every subject that you were taking, and if you failed to maintain the proper pace with the rest of your classmates, you were washed out and you left the status of being a cadet to become one of just a private in the Air Force or in the Army Air Corps. So you were sent off to someplace for basic training,” he told the AMS.

Anderson’s colleague Archie Williams also wanted to be a pilot initially. And while he knew how to fly a plane — Williams was a civilian flight instructor at Tuskegee — and he was in fine physical condition — the former track star had won the gold medal in the 400-meter in the 1936 Olympics — he was nearly 27 at the outset of the war, too old for military flight training.

Because he had studied engineering at UC Berkeley, Williams was ushered into meteorology — although he continued to train pilots at Tuskegee.

“While I was there, I had three jobs. I was a weather officer. I was drawing weather maps, making weather forecasts, and teaching intro to flying,” he said in a 1992 interview with UC Berkeley.

While Williams, Anderson, and a handful of others found a place in the service, many more qualified black men were left on the sidelines. Judge William Hastie, civilian aide on Negro affairs to the secretary of war, resigned over frustrations with discrimination in recruiting. In a 1943 pamphlet published by the NAACP, Hastie wrote about qualified black applicants who were prevented from serving at a time when the Army Air Force was desperate to enlist meteorologists.

The 14 Tuskegee meteorologists accounted for just one-fifth of 1% of all weather officers in the Army Air Forces. Black pilots and other personnel were similarly few in number, and they were regarded with intense suspicion.

“Of course, when they started talking this flying stuff, that was crazy. They said that the jump from the plow to the plane is too much for" African Americans, Williams said. “We were supposed to fail; they expected us to fail.”

The Tuskegee Airmen would come to defy those expectations while escorting B-17s on bombing raids over Europe, proving themselves more capable than many of their white peers.

“Of the 179 bomber escort missions, they lost bombers to enemy aircraft on only seven of those missions,” retired Air Force historian Dan Haulman said in an interview, adding that they lost only 27 bombers in total, while other groups lost 46 bombers on average. He said that accurate weather forecasting was critical to their success, as pilots needed to know what conditions to expect on their missions.

"Just as the black pilots proved that they could fly military aircraft in combat as well as the white pilots, so did the black weather personnel prove that they could perform meteorological functions as well as the white officers," he said.

» READ MORE: Tuskegee Airman, 90, serves up meals and stories at South Jersey senior center

Asked if he thought the Tuskegee Airmen helped change attitudes, Williams said, “Damn right it did. Sure it did. Because a lot of guys there were bigoted. The white guys didn’t want to fly with them and all, but they found out that these guys could fight, could shoot good, and protect the bombers.”

In July, 1948, Harry Truman finally ended segregation in the military. Williams stayed on after the war, eventually serving in Korea. Reed took a job as a meteorologist for Pan American Airways in the Philippines and later worked for the Weather Bureau.

Anderson earned his Ph.D. at MIT and went on to teach at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where he was the chair of the meteorology department. The American Meteorological Society has named an award for Anderson recognizing work promoting diversity in the atmospheric sciences.

Meteorologist Marshall Shepard, director of the atmospheric sciences program at the University of Georgia, and a recipient of the Charles E. Anderson Award, spoke to the legacy of the Tuskegee Weather Detachment.

“As we celebrate Black History Month, it is important to acknowledge the contributions of people that look like me in STEM fields. Numbers remain woefully low for African Americans, and a lack of mentors and inspirations are reasons why,” he said in an email. “The pioneering work of the Tuskegee Weather Detachment, Anderson, and others must be celebrated and disseminated. It’s not just Black History. It is American History.”