From ‘cancel culture’ watchdog to Trump antagonist

FIRE, the Philly-based free speech organization, is now defending universities it long criticized.

The sleek, modern offices of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, or FIRE, sit on the southernmost edge of Independence Square. The enormous glass windows of a conference room called the Marketplace — a nod to the “marketplace of ideas” — perfectly frame Independence Hall.

The view is no coincidence. The free-speech organization, founded in 1999 and long known for decrying illiberalism and so-called cancel culture on American college campuses, is deliberate in the stories it tells.

In addition to the thousands of case submissions FIRE receives each year, staffers scour social media and news reports for compelling free-speech violations, partly looking, as legal director Will Creeley explained, for “cases you can tell a story with.”

For years, FIRE warned about threats to free speech, primarily on college campuses. Now the crisis it was preparing for has arrived.

The issue today is no longer one of cultural differences — students protesting controversial speakers or agitating for more diverse curricula.

Instead, the full power of the federal government is trained on universities and individual students who disagree with it. The stakes have grown exponentially, as became clear early on when federal agents detained Rumeysa Ozturk, a Tufts University Ph.D. student on a visa, after she cowrote an op-ed in a student newspaper. She then spent 45 days in Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention in Louisiana. (FIRE submitted an amicus brief in Ozturk’s ongoing federal case, in which a federal judge ruled last month that the administration had no grounds to deport her.)

More recently, federal agents arrested and charged journalist and former CNN anchor Don Lemon with federal civil rights crimes for his coverage of an anti-ICE protest inside a Minnesota church. Of his arrest, the organization wrote, “FIRE will be watching closely.”

The question FIRE faces today is whether it can effectively meet the moment, and overcome skepticism from the left and from other free-speech advocates, some of whom argue the group helped lay the groundwork for an authoritarian crackdown.

Those critics say the present free-speech crisis is partly the predictable result of FIRE stoking a conservative panic over campus politics, effectively handing the federal government a well-crafted rationale for suppressing progressive voices.

FIRE’s leaders say they were not wrong before about cancel culture. Things were bad, they argue. But this is far worse.

“The threats we’re seeing right now, to me, often feel damn near existential,” Creeley, 45, said in a recent interview. “The incredibly important distinction is that what we’re seeing now from the right is backed by the power of the federal government.”

When the government becomes the censor

It can sometimes feel as if FIRE has been involved in nearly every major free-speech flash point of the last year — part of an intentional strategy to build the organization’s profile and raise awareness about speech violations, said Alisha Glennon, 41, the group’s chief operating officer.

Among dozens of ongoing cases, FIRE is suing Secretary of State Marco Rubio in federal court over the administration’s targeting of international students who reported on or participated in pro-Palestinian campus activism.

FIRE has also been outspoken in its defense of Harvard University. After the Trump administration sent Harvard a list of demands this spring — including banning some international students based on their views, appointing an outside overseer approved by the federal government to ensure “viewpoint diversity,” and submitting yearly reports to the government — the university refused to comply. Trump then sought to cut off billions of dollars of federal funding in response.

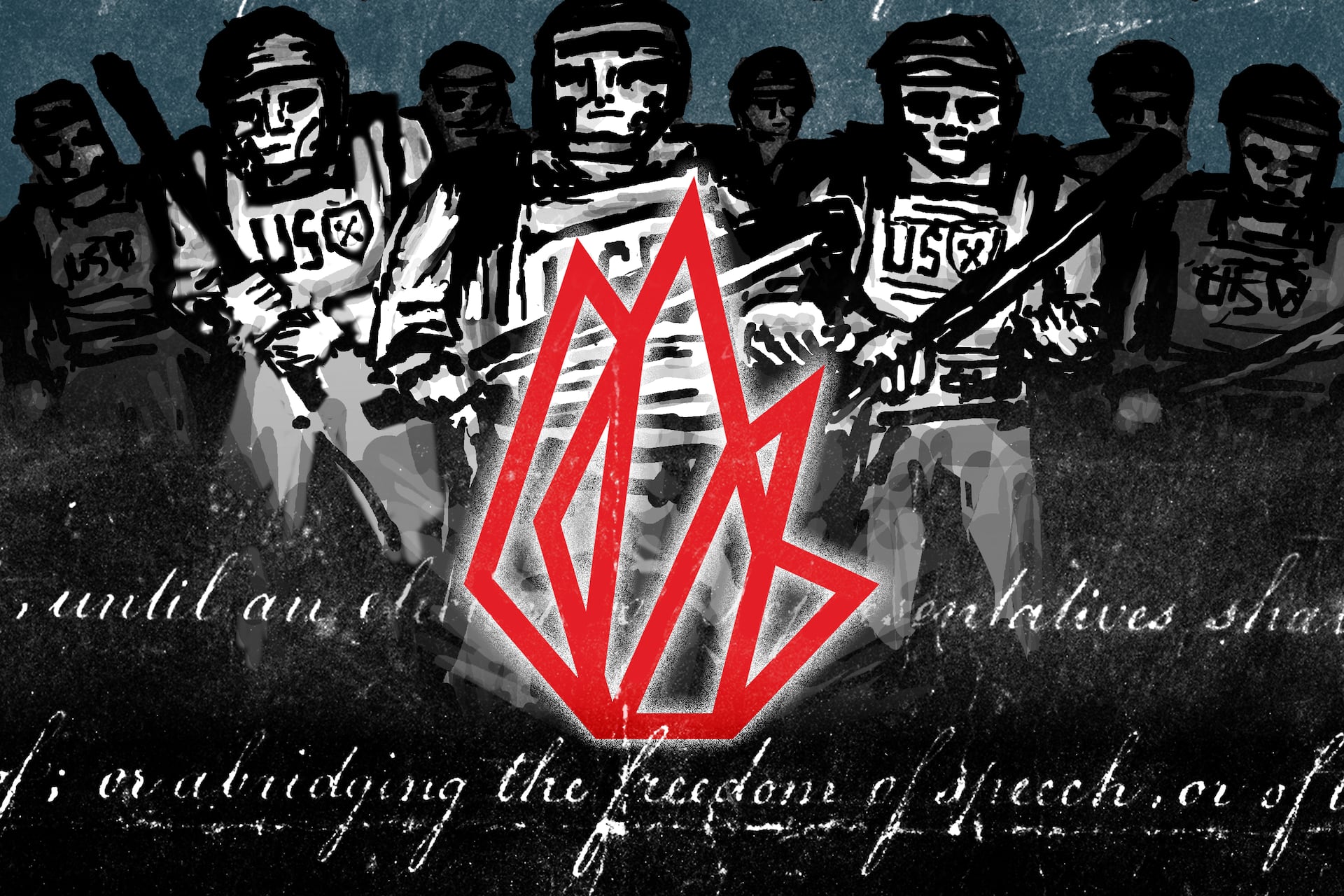

Harvard sued, and FIRE submitted an amicus brief supporting the university, noting that because of its own “longstanding role as a leading critic” of Harvard as a center of cancel culture, it was not less but more alarmed by the government’s “wielding the threat of crippling financial consequences like a mobster gripping a baseball bat.”

FIRE is also preparing to potentially sue Texas A&M University after the university instructed a philosophy professor in January to remove some teachings of Plato from an introductory philosophy course, citing new rules barring public universities in the state from offering classes that “advocate race or gender ideology.” FIRE wrote to the university, calling the move “unconstitutional political interference.”

Removing Plato from an intro philosophy class is the type of absurd, taken-to-the-extreme free-speech dispute that has long been FIRE’s bread and butter, and Creeley was particularly agitated about it.

“What the hell is ‘race and gender ideology’?” he said. “That’s a term so vague you could drive a truck through it.”

He had seen commentary about how 2,400 years ago, Socrates was put to death for corrupting the youth of Athens — and now administrators were, in effect, trying to run Socrates’ student out of College Station, Texas, too.

Creeley was almost laughing, but he was also feeling apocalyptic.

He has been half-joking with his staff that FIRE’s entire litigation program could be dedicated just to Texas. Yet he was also stewing over a decision by the University of Alabama in December to suspend two student publications, one focused on fashion and the other on Black culture and student life.

The university said both violated the Justice Department’s guidance on diversity, equity, and inclusion by narrowly appealing to female students and Black students. FIRE sent an outraged letter to the school, often a precursor to litigation.

It’s one thing to say, ‘Hey, administratively, we’re not going to have an office of DEI.’ ... [But to say,] ‘And students can’t talk about these things’… That just drives me nuts.

“It’s one thing to say, ‘Hey, administratively, we’re not going to have an office of DEI,’” Creeley said. But to say, “‘And students can’t talk about these things.’ … That just drives me nuts.”

Off campus, FIRE is suing Perry County, Tenn., on behalf of Larry Bushart, a retired police officer who spent 37 days in jail after reposting a meme following the assassination of right-wing political activist Charlie Kirk. The meme depicted then-presidential candidate Donald Trump urging people to “get over” a separate shooting the year before.

Defending free speech is notoriously unpopular, and FIRE has leaned hard into a narrative of itself as a pure, principled defender of free speech, regardless of the consequences.

“We always say we just call balls and strikes, no matter what team is up to bat,” Glennon said. “If you are being criticized by both sides and praised by both sides every single day — well, then, that’s something that I wear as a point of pride.”

“Sometimes, if everybody’s criticizing you, you are screwing up,” Creeley acknowledged, and they both laughed. “But here I would say we’re doing it right.”

From scrappy watchdog to national player

FIRE is insistently nonpartisan; staffers acknowledge the organization’s erstwhile conservative reputation but say it was never accurate.

And under the second Trump administration, it has become one of the most outspoken voices in the country for free expression. The nonprofit has a $32 million budget, about 130 staffers, and roughly 12,000 members paying a $25 annual fee.

Both Creeley and Glennon have been with the organization for nearly two decades, helping it grow from a small advocacy group into one garnering increasing mainstream attention. They said FIRE based itself in Philadelphia, not Washington, so that it would remain free from political interference. (One of the cofounders of the organization, Alan Charles Kors, an emeritus history professor at the University of Pennsylvania, is also based in Philly.)

At the Philly office, copies of the Wall Street Journal and the Chronicle of Philanthropy greet visitors. The conference rooms are named after free-speech references. (“It’s a little kitschy, but it’s cute,” Glennon said of the “Crowded Theater” room.)

One afternoon this fall, Glennon, in an oversized tan blazer, black pants, and stilettos, her blond hair loose, and Creeley, in a white button-down and purple tie, his auburn beard neatly cropped, were quick to laugh, prone to peppering famous quotes about free speech throughout the conversation.

They appeared to be true believers — in free expression, in their work, in America.

Glennon said she fears “that people will become accustomed to a society that is less free, and that with every generation, we’re losing a little bit of that love for American exceptionalism and what free speech is.”

Creeley nodded.

“What’s the Kors quote? ‘A nation that does not educate in liberty will not long enjoy it, and won’t even know when it’s lost,’” he said, paraphrasing a quote from FIRE’s cofounder.

“‘Won’t even know when it’s lost,’” Glennon echoed. “Gave me chills.”

From pressure campaigns to the courtroom

FIRE was founded by two civil libertarians who wrote one of the defining campus-panic books of the 1990s, The Shadow University: The Betrayal of Liberty on America’s Campuses, which Publishers Weekly at the time described as a polemic about how “the ‘political and cultural left’ is today the worst abuser of the principles of open, equal free speech.”

Creeley joined FIRE as a law school intern before becoming a full-time staffer in 2006. He comes from a long line of pacifist Quakers and was involved in the campus Green Party as an undergrad at New York University. He said he was drawn to First Amendment work because his father was a poet; words were important.

“I remember the first couple years, I was like, ‘Boy, I’m doing this free-speech work, I’m defending an awful lot of evangelical conservative Christians who I really don’t have much in common with,’” Creeley said. But that was the principle of the thing.

Glennon, who was born and raised in Mayfair, joined FIRE around the same time. She had recently graduated from the College of William and Mary and was waitressing while applying for development jobs. “I was like, ‘Free speech! Everybody likes free speech!’” she said, laughing.

For more than a decade, FIRE focused exclusively on advocacy, aiming to “make rights violations so painful for a school that they just would abandon it,” Creeley said. Litigation was plodding and costly, and the awareness campaigns seemed to have an impact.

In 2008, for example, a student-janitor at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis was accused of racial harassment after a coworker saw him reading Notre Dame vs. the Klan: How the Fighting Irish Defeated the Ku Klux Klan, a nonfiction book that depicted robed Klansman and burning crosses on the cover. FIRE took up the cause, and the university eventually apologized to the janitor.

Other early advocacy cases included defending a professor at a New Jersey community college over a photo he posted of his daughter wearing a Game of Thrones T-shirt, and intervening on behalf of a University of Alaska Fairbanks student newspaper accused of sexual harassment for publishing a satirical article about a new building shaped like a vagina.

Then in 2014, FIRE began suing schools. The effort launched with four cases, including one about an unconstitutional “free speech zone” at a college in California and one on behalf of students at Iowa State University who were told they could not use the university’s name while wearing T-shirts representing their chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws.

FIRE eventually won all four.

These days, staffers at the ACLU of Pennsylvania and FIRE work closely together, talking weekly and sometimes daily.

I honestly don’t remember a time where we had a disagreement about how to analyze the case.

“I honestly don’t remember a time where we had a disagreement about how to analyze the case,” said Witold Walczak, the ACLU of Pennsylvania’s legal director.

Despite its ideologically broad legal work, FIRE perhaps became most famous in the mainstream for its conservative-leaning culture work. In 2015, executive director Greg Lukianoff cowrote an Atlantic article — and later a book — titled The Coddling of the American Mind, arguing that efforts to create “safe spaces” on campuses had gone awry. Cowritten with social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, the book portrayed campus identity politics as bordering on the surreal.

That was also the year Lukianoff helped to disseminate one of the defining “cancel culture” artifacts of the decade. He filmed a Yale student, who came to be known online as “shrieking girl,” screaming at a professor in the middle of a simmering debate on campus over what constituted racially sensitive Halloween costumes. The video made national news, eventually racking up nearly 2 million views on FIRE’s YouTube page.

The rankings — and the reckoning

These days, the organization tracks speaker disinvitations and scholars and students “under fire” through its public databases. Since 2020, it has also published annual “free-speech rankings” based on the databases and student surveys — rankings that have repeatedly placed Harvard at or near the bottom for free speech.

Those efforts underpin one of the central critiques of FIRE: that it has focused not only on government restrictions but also on the actions of private actors, including students.

“The rankings are based on those ideas of ‘cancel culture’ and shaming others and so on. And they’re not based on the First Amendment,” said Charles Walker, a retired attorney based in Maryland who published multiple critiques of FIRE’s rankings last year. “First Amendment law restricts what the government can do with regard to individual speech. It doesn’t address individuals speaking to each other.”

Bradford Vivian, a professor at Pennsylvania State University and the author of Campus Misinformation: The Real Threat to Free Speech in American Higher Education, described FIRE’s databases as “totally subjective, arbitrary, politically motivated tools.”

He argued that FIRE cherry-picks sensational incidents that do not necessarily have anything to do with true First Amendment violations, and prioritizes rankings that will make headlines over those that would be more accurate.

FIRE has produced misinformation that others can easily use for nefarious purposes.

“FIRE has produced misinformation that others can easily use for nefarious purposes,” Vivian said.

FIRE for years whipped up a frenzy over liberal excess on elite college campuses, Vivian and other critics say. The Trump administration seized on that frenzy to slash federal funding and even imprison its detractors. Yet FIRE staffers do not see themselves as part of that story.

Even as FIRE insists it merely “calls balls and strikes,” critics note that state legislatures and the Trump administration have cited FIRE’s rankings as justification for punitive actions against universities.

Adding insult to injury, FIRE staffers have not always expressed much sympathy for the universities that now find themselves in the administration’s crosshairs.

“Administrators, colleges, universities have in some ways done plenty to bring this on themselves,” Sean Stevens, FIRE’s chief research adviser, told The Inquirer. “There was a lot of downplaying or ignoring of the concerns about the homogeneity of politics among the professorate or some of the curriculums.”

Still, Stevens, who oversees the annual rankings, said he disagrees with the Trump administration using his work to cut funding or shut down certain speech or academic departments. “That’s not anything we would advocate for,” he said.

In December, Lukianoff doubled down, publishing what amounted to an “I told you so” essay, arguing that universities now face a “worst of both worlds” scenario, in which government pressure combined with lingering cancel-culture dynamics are producing the “bleakest speech landscape imaginable.”

Creeley and Glennon said they never anticipated their work being used to justify repression.

It’s galling to me to see our work invoked to justify that kind of illiberal crackdown.

“It’s galling to me to see our work invoked to justify that kind of illiberal crackdown,” Creeley said, pointing specifically to U.S. Rep. Elise Stefanik (R., N.Y.), who previously said she was a free-speech ally, using FIRE’s rankings in her anti-higher education campaigns.

If onetime allies now seem to have never cared much about free speech to begin with, that’s not on FIRE, they said.

“What we had been saying over the years was true‚” Glennon said. “We’re to blame now for the government overreach? I don’t think it’s a fair assessment.”

“I mean, that’s all we can do: Call out the abuses as we see them,” Creeley said. “If somebody wants to use our work for bad ends, we’ll fight you on it.”

Can a referee still matter when the rules change?

At FIRE’s daily morning meetings to discuss pressing free-speech problems across the country, the agenda has grown longer. The scope, severity, volume, and nature of the cases they are seeing have changed, Creeley said. (He noted — twice — that an Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez presidency would likely keep FIRE busy as well.)

“In some places, the law is just getting flat-out ignored,” he said.

After two decades defending the First Amendment, Creeley has begun to reflect on whether placing his faith in the collective commitment to the law and the Constitution was the right choice. Still, he remains an optimist. He believes that such a commitment will prevail. That’s the whole promise of the country.

FIRE continues to see itself as a principled referee. Whether a referee still matters when the most powerful player insists the rules no longer apply — that remains an open question.