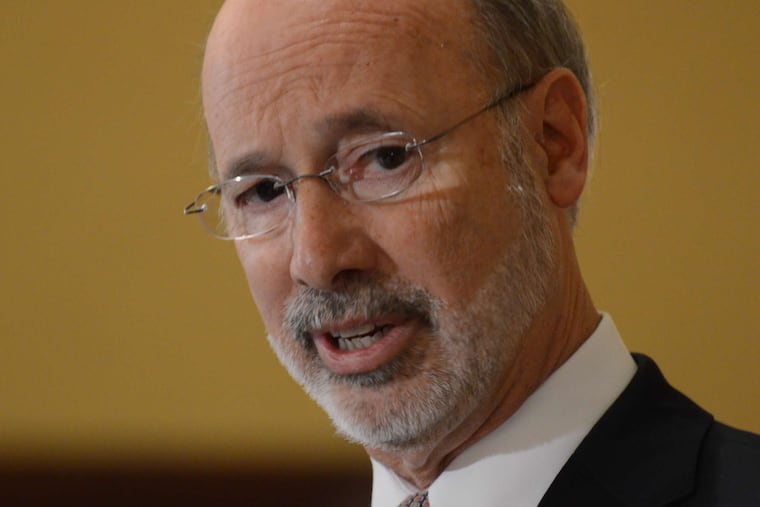

Gov. Wolf frees Chester County man sentenced to 122 years on drug charges, weighs more acts of clemency

Wolf has signed off on commuting the sentence of Benny Ortega, a Chester County man who has served 22 years of a 125-to-292-year sentence for selling marijuana and cocaine.

HARRISBURG — In his first act of clemency in more than two years, Gov. Wolf has ordered one inmate to be freed, and is weighing commuting the sentence of at least one other person sentenced to life in prison, according to administration officials.

Wolf on Monday agreed to commute the sentence of Benny Ortega, a West Chester-area man who has served 22 years of a 125- to 292-year sentence for selling marijuana and cocaine. The governor has for the last few weeks been considering clemency recommendations by the state Board of Pardons for dozens of people, including Ortega, according to his staff.

In a statement Tuesday, Wolf spokesperson J.J. Abbott said the governor believed Ortega’s prison term “was egregious and inhumane,” and cited the rehabilitative steps the man has taken in prison.

“He has used his time while incarcerated to get treatment and gain skills to rejoin the workforce,” Abbott said. "His sentencing represents the need for criminal justice reform. Gov. Wolf encourages Pennsylvanians that have been treated similarly to apply for commutation.”

The Inquirer and Daily News reported last week that critics of the system, including Wolf’s outgoing lieutenant governor, Mike Stack III, fear that the state’s pardons system is effectively broken, and fails to give worthy inmates a chance they deserve.

Wolf’s decision to free Ortega was his first commutation since 2016, and only his third since taking office in 2015, according to information collected by the Board of Pardons.

For inmates sentenced to life in prison, there is no parole; commutation is the only path to release. The Pardons Board, composed of state officials and appointees, is the only entity with the authority to make recommendations to the governor for clemency — governors can’t do so on their own.

Those who receive commutations must spend a year in a state-run halfway house before returning to the community.

In a recent interview, Ortega, 60, said his biggest fear was that after a year of hope — the board recommended clemency for him in the fall of last year — Wolf would reject his petition.

“It’s been a stressful year,” Ortega said.

Wolf is also considering commuting the life sentence of Tina Brosius, a Dauphin County woman who was convicted in 1995 of allowing her newborn baby to drown in a portable toilet. Brosius, 43, would be the first woman in nearly three decades to receive a commutation of her life sentence.

Her 27-year-old daughter, Kerri Brosius, has been waiting for her mother to come home before setting a date for her wedding. The Board of Pardons recommended her mother for commutation in September 2017.

“The waiting part is the worst,” the younger Brosius said.

Ortega said his plans upon leaving prison include working in his family’s landscaping service, spending time with his mother, who is 77 (his father died while he was incarcerated), and getting to know his three young grandsons, whom he’s never met.

“I just don’t like to have my grandchildren come here,” he said. “I don’t want them to get the idea it’s OK.”

Ortega had been addicted to cocaine and was in debt in the early 1990s when an acquaintance offered him the opportunity to pitch in with a drug-distribution scheme. He was convicted of 90 counts of selling marijuana and cocaine.

Now, he’s the chairman of Phoenix state prison’s Narcotics Anonymous program.

“Even though my crime is a nonviolent crime, it is not a victimless crime," he said. "But also, the War on Drugs is the most devastating thing that could have happened. When a guy’s got a third-degree murder and he’s going home and I’m not, it does sometimes upset me.”

To him, the worst part was that his wife, Doretha, who he insists was not involved in the operation and was never a drug user, was also convicted, and sentenced to 5 to 23 years in prison.

Doretha Ortega, 57, of West Chester, has been on parole for 18 years now and is still married to Benny. Divorcing him in prison just seemed too cruel. But she hasn’t been to see him in about a decade.

“I used to go up there all the time, but it just started getting to be too much,” she said. She would have flashbacks to the day of the bust. “I have a lot of anger, a lot of bitterness in me because of that.”

Her life has never been the same. After she came home from prison, she looked into nursing school but was told she’d never get licensed. She studied to be a medical assistant instead.

“I graduated with honors and yet I can’t do the job. They won’t hire me, and I know it’s because of the record,” she said. “I just gave up all that. I still have the student loans to pay.” She’s been working as a machine operator; it’s what she could get.

Benny Ortega hopes they’ll date when he gets home, and eventually get back together. Doretha isn’t sure.

“I was so so in love with him. But I’m not a real forgiving person,” she said. “It’s been a long time. We just have to start all over again and see where it goes.”