The FBI break-in that exposed J. Edgar Hoover’s misdeeds to be honored with historical marker in Media

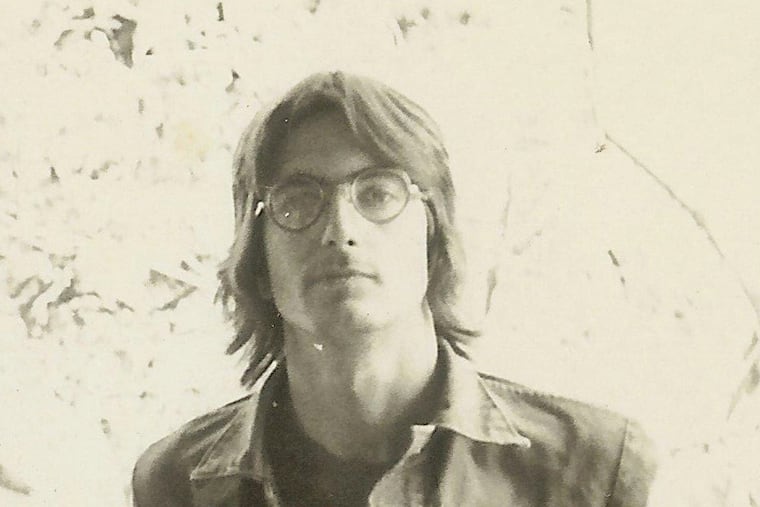

Outraged by the Vietnam War, 20-year-old Keith Forsyth dropped out of college in Ohio and moved to Philadelphia to join the vigorous antiwar movement there.

Outraged by the Vietnam War, 20-year-old Keith Forsyth dropped out of college in Ohio and moved to Philadelphia to join the vigorous antiwar movement there. He took a lock-picking course so he could help with late-night break-ins at local draft boards, where protesters stole or destroyed files to disrupt the flow of young Americans to Southeast Asia.

Bonnie Raines, a 29-year-old mother of three, was a veteran of the draft board raids. Then, in early 1971, one of the antiwar leaders suggested an escalation in tactics: burglary of an FBI office in the hope of finding documents that might prove the bureau was illegally spying on and harassing antiwar protesters. Raines agreed to join, and she went undercover as a "scruffy coed" to "interview" an FBI agent at a suburban resident agency in Media, Pa., while carefully scanning the office to note all doors, file cabinets and security measures.

» READ MORE: 50 years later, an historic act of civil disobedience in Delco is finally getting its due | Will Bunch

The date was set: the night of March 8, 1971, while much of America would be absorbed with the first Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier title fight on the radio. Forsyth went into the unlocked building, only to find a new second lock on the FBI office. He couldn't pick it. He left, and the nervous group considered aborting the mission, knowing they faced years in prison if caught.

But Raines told him there was a second door, blocked by a file cabinet. Forsyth returned, picked another lock and snapped off the deadbolt. Then he lay on the floor and slowly pushed the file cabinet enough to open the door. Minutes later, four of his colleagues swooped in and filled multiple suitcases with FBI files and quietly drove away, not knowing if they'd found anything of value.

What they found uncovered a nationwide program of illegal surveillance and harassment, which in turn led to the discovery of J. Edgar Hoover's invasive COINTELPRO operation, congressional hearings and ultimately oversight of the FBI after it had operated autonomously for decades and openly referred to its headquarters as "the Seat of Government."

And the activists got away with it. Despite an intensive investigation overseen by Hoover, the burglars were never caught, even as they repeatedly supplied stolen files to The Washington Post and other media outlets that blasted out the revelations of Hoover's intent to "enhance the paranoia" of antiwar activists.

Former Post reporter Betty Medsger, who broke the initial stories, revealed the burglars' identities and the context of their case in her 2014 book, "The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover's Secret FBI."

Now, the state of Pennsylvania is commemorating the crime. On Wednesday, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission will dedicate a historical marker at the building in Media where the burglary occurred.

Medsger, Raines and Forsyth will attend, along with the town's mayor and a former FBI agent, to acknowledge the significance of the burglary in changing the way the FBI works and how the United States views its intelligence machinery.

"The most amazing and shocking thing about the Media burglary," said Sanford J. Ungar, author of the book "FBI: An Uncensored Look Behind the Walls," "was that the files stolen that day and distributed in the weeks and months to come proved that the worst accusations and conspiracy theories about the FBI's behavior at the time were utterly true. In many respects, the agency never regained its reputation, sometimes actually deserved, as one of the greatest law enforcement agencies in the world."

"One word defines the burglars - determination," said former NBC reporter Carl Stern. "They were determined to find something, they didn't know what, that would confirm that the FBI was going over the line to harass and 'neutralize' organizations and individuals whose political activities it detested."

Stern would play a crucial role in the FBI's unraveling when he seized on one word in one stolen document that neither the media nor the burglars had examined: "COINTELPRO." He began asking what that word meant. No one would tell him. Eventually, he and NBC sued to find out what it meant, and won. And after he began receiving COINTELPRO documents in 1973, he helped unearth some of the FBI's worst crimes:

- The surveillance and harassment of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., sending him letters urging him to commit suicide, sending a recording of him having sex with other women to King's wife (and offering it to journalists) and attempting to blackmail King.

- The murder of Black Panther Fred Hampton by Chicago police, set up by an FBI informant.

- The suicide of actress Jean Seberg, after the FBI planted a story with a news columnist that she was pregnant by a Black Panther.

The revelations about COINTELPRO, a program begun by Hoover in 1956, led to congressional hearings by the Church Committee, new rules on how and why FBI investigations should be conducted, a 10-year term limit for FBI directors, and continuing congressional oversight of the bureau by House and Senate committees.

"It's hard to imagine today," Medsger said, "but there really wasn't much critical coverage of the FBI. They were regarded as outside government accountability." She said that if Stern hadn't become preoccupied with uncovering COINTELPRO, "the rest of the story might not have happened, and the reforms would never have happened. Getting COINTELPRO out there changed everything."

The burglary was planned by William Davidon, a physics professor at Haverford College and leader in Philadelphia's antiwar movement. He recruited John Raines, a religion professor at Temple University, Raines's wife, Bonnie, the amateur locksmith Forsyth, and five others.

Forsyth said the group originally examined the FBI's Philadelphia field office, but there was too much security. He said Davidon discovered the smaller "resident agency" in Media, then a town of about 6,400 west of the city. The group began watching the movements of people in and out of the building, and Bonnie Raines conducted her phony interview with an agent, on "opportunities for women in the FBI" she said, to case the inside of the Media office.

Forsyth had made trips into the building to examine the locks, and found that the main lock could be easily picked. But on the night of March 8, he arrived to find a new second lock installed.

"It really freaked me out," Forsyth said in an interview. He returned to the rest of the group, and they all wondered if the FBI was onto their plan.

It turned out that top FBI executive Mark Felt was indirectly responsible, Medsger and the burglars later found. Records showed that the agents in Media had asked for more security for their office, and Felt had turned them down. So the agents had taken it upon themselves, in the days before the burglary, to install a second lock.

About a year later, Felt would begin providing information to Post reporter Bob Woodward about the Watergate break-in and would be famously nicknamed "Deep Throat."

Raines told Forsyth about the second door and the file cabinet behind it. Forsyth went back, unlocked it and gradually got it open.

Four other members of the group then came in and grabbed every file they could carry. A security guard at the Delaware County Courthouse across the street watched them load up a car with suitcases, Forsyth said, but later told the FBI he didn't see anything. When the agents later realized that the "college interviewer" was probably part of the group, the agency produced a composite drawing of her, but Bonnie Raines was never identified.

The group took the files to a farmhouse outside of Media and stayed up until dawn to see if they'd found anything worthwhile. Almost immediately, they found they had: a document advising agents who investigated activists to "enhance the paranoia . . . get the point across there is an FBI agent behind every mailbox."

In another, FBI agents were advised by Hoover directly: "Effective immediately, all BSUs [Black Student Unions] and similar organizations organized to protect the demands of black students, which are not presently under investigation, are to be subjects of discreet, preliminary inquiries . . . to determine background and if their activities warrant active investigation."

Now, the burglars had to share this information with the world. Davidon decided to anonymously mail copies of the FBI documents in small chunks, Medsger said in an interview, rather than unload a vast amount of information at once and have reporters emphasize only one aspect of the revelations. The mailings of 10 to 14 pages would occur every few weeks for the next two months, sparking a new uproar each time.

The package from the "Citizens Commission to Investigate the FBI" was sent to two members of Congress and three journalists, but only Medsger immediately moved to report on its contents. She was a 29-year-old religion reporter who had come to the paper a year earlier from the Philadelphia Bulletin. As a religion reporter there, she'd profiled John Raines's moves to expand the theology curriculum at Temple and also covered the deep Catholic involvement in the antiwar movement.

The Raineses "thought Betty would take it seriously," Bonnie Raines said.

Medsger took the package to The Post's National desk, where a Justice Department reporter helped confirm that the documents were authentic. Then, events unfolded that would presage the arrival, and publication, of the Pentagon Papers just three months later.

Attorney General John Mitchell called The Post and demanded the paper not publish anything about the documents. He issued a news release declaring the stolen papers off-limits to anyone who received them. Post attorneys advised publisher Katharine Graham not to publish a story about them.

Medsger was unaware of these high-level machinations. She was writing. Editor Ben Bradlee "insisted it was very important, it should be in the paper," Medsger said. At 10 p.m., Graham made the decision to publish.

In June 1971, Graham again faced pressure from Mitchell and others not to publish stories about the Pentagon Papers. Again, she approved publication.

Hoover's FBI mainly survived the initial uproar from the revelations Medsger reported and pushed in vain to find the burglars. Then in the summer of 1972, NBC's Stern went to a Senate Judiciary Committee office to pick up some documents, and while he waited, he leafed through some of the papers released from the FBI burglary.

In one document were the handwritten words, "COINTELPRO New Left." The document suggested that agents mail anonymous letters to college administrators "who have shown a reluctance to take decisive action against the 'New Left.'"

What is COINTELPRO? Stern wanted to know. No one could, or would, tell him. In early 1973, he filed a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit. By the fall, U.S. District Judge Barrington Parker had reviewed a small sample of COINTELPRO documents - the word is short for "counterintelligence programs" - and ordered them released to Stern.

Stern received just four pages. But one of them revealed there were at least seven COINTELPROs targeting groups such as the Communist Party, the "New Left," "White Hate Groups," "Black Extremists" and the Socialist Workers Party. Stern filed another lawsuit seeking more documents, and in 1974 received 50,000 pages.

The surveillance and harassment operations ruined countless lives, Stern said. In Los Angeles, Black Panther Party leader Geronimo Pratt was falsely convicted of murder in part through the perjured testimony of an FBI informer, even though the FBI knew from wiretaps that Pratt was 350 miles away when the crime happened. Pratt spent 27 years in prison. In New York, the bureau wrote a false letter identifying one of the leaders of the Communist Party, William Albertson, as an FBI informer. Albertson was promptly booted out of the party.

"Numerous Black people were falsely accused," Medsger said, "on perjured testimony by FBI agents. People around the country went to prison for decades. The most important thing about the files were what they revealed about the depths of Hoover's racist practices, and their Stasi-like collection of files on people, particularly Black people."

In January 1975, the Church Committee was formed in the Senate, headed by Sen. Frank Church, D-Idaho, to investigate reported abuses committed by the FBI, the CIA and the National Security Agency. The revelations about the FBI led to the "Levi guidelines" issued by Attorney General Edward Levi in 1976, which required the bureau to have "specific and articulable facts" that an individual or group may be engaged in violence or violation of federal law. Time limits were placed on investigations, the FBI in Washington had to approve informers, and the attorney general had to approve mail interceptions and "other invasive investigative methods," Medsger wrote.

In 2016, West Chester University graduate student Kevin Tustin was working on a project about government surveillance and came across a video called "The Greatest Heist You've Never Heard Of," about the Media burglary not far from his hometown. He became familiar with the process for securing a historical marker in Pennsylvania, had it approved in 2019, and helped arrange for the ceremonial unveiling after a coronavirus-related delay in 2020.

Meanwhile, the eight burglars had promised never to reveal themselves and went their separate ways. But in 1988, John Raines casually divulged the plot to Medsger over a family dinner. Medsger persuaded the Raineses to connect her with the other burglars, beginning a 26-year journey that would lead to a documentary film, "1971," by Johanna Hamilton, which premiered soon after Medsger's book revealed the entirety of the case in 2014.

"Our friends here in Philadelphia were just utterly shocked," Bonnie Raines said. Her husband died in 2017. "Now there'll be this big historical marker, which I think is just a hoot. Fifty years ago, we were criminals, and now we're heroes."

Forsyth said his Midwestern upbringing made him reluctant to take credit for his role in such a historic event. “But if it brings these political issues to others’ attention,” Forsyth said, “like, ‘When is it right to break the law? What is right for a government to do in a democracy? What should be secret or not secret?’ If it provokes discussions of that, then I’m all for it.”