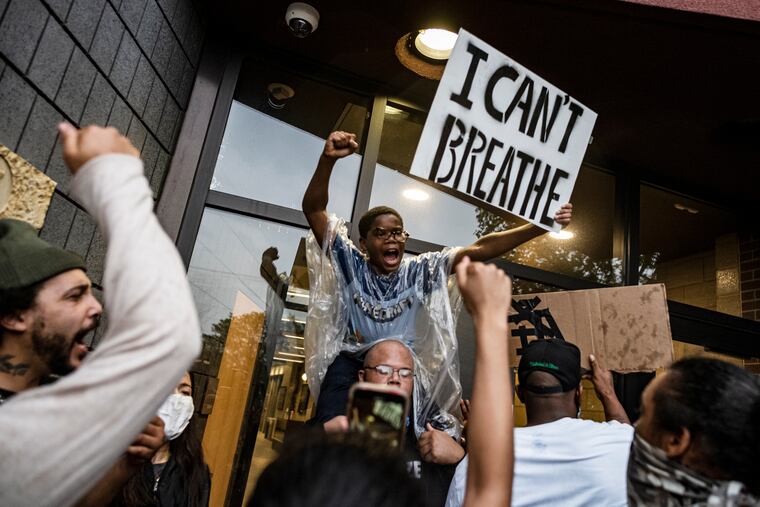

Chaotic scene in Minneapolis after second night of protests over death of George Floyd

A peaceful protest earlier in the evening descended into disarray and looting. Officers stood in front of a precinct and tried to disrupt the crowd with flash bang grenades and rubber bullets.

MINNEAPOLIS — Thousands of people poured into the streets here for a second night of protests — which later turned chaotic as police fired rubber bullets from a rooftop, several buildings caught fire, and one person was shot and killed by a store owner — after a viral video showed a white police officer putting his knee on the neck of a black man, who later died.

A peaceful protest earlier in the evening descended into disarray and looting. A group of officers stood in front of a nearby precinct and tried to disrupt the crowd with flash bang grenades and rubber bullets. At times, the tear gas was so thick, it wafted down neighborhood streets where people standing in their front yards were coughing and wiping at their eyes.

By 10 p.m., an Auto Zone had caught fire. Soon, other fires erupted, including a massive blaze at a construction site. Meanwhile, one person was shot by a pawn shop owner and died at a hospital, police told the Star Tribune, as looters ransacked a Target, Foot Locker and nearby small businesses.

Mayor Jacob Frey, D, has requested help from the state's National Guard as local leaders pleaded for a peaceful resolution.

"Violence only begets violence. More force is only going to lead to more lives lost and more devastation," Rep. Ilhan Omar, D-Minn., tweeted.

The scene followed the death of 46-year-old George Floyd on Monday, which came after a white officer pinned the handcuffed father of two to the pavement outside of a market where employees had called police about a counterfeit bill. The police encounter was caught on a viral video that has sparked national outrage and inflamed existing tensions in a community where cops have long been accused of racism.

In the suburb of Oakdale, hundreds of protesters on Wednesday gathered outside the home of Derek Chauvin, the police officer who was captured on the video with his knee on Floyd's neck. According to the Star Tribune, red paint was poured onto Chauvin's driveway, and the word "killer" was written on the garage door.

Police Chief Medaria Arradondo swiftly fired Chauvin after Floyd's death, along with the three other involved officers, identified by authorities Wednesday as Thomas Lane, Tou Thao and J. Alexander Kueng. President Donald Trump on Wednesday tweeted that he had asked the FBI, which is investigating the death, to expedite its work, adding that "Justice will be served!"

But the response from authorities has done little to assuage a community that says it has long suffered undue treatment by local officers and has called for the officers' arrests.

The protests here on Wednesday were reminiscent of those that followed the 2017 death of Philando Castile, who was sitting in his car after a traffic stop in a nearby suburb when an officer shot him.

When his nephew was killed, Clarence Castile made every effort to understand how something so horrific could have happened: He began attending sessions at the Peace Officer Standards and Training Board to learn about rules governing the use of force. He became a St. Paul Police Reserves officer. And, last year, he joined a task force convened by the state attorney general to develop recommendations on how to reduce deadly-force encounters involving police statewide.

But when he saw the video of Floyd's encounter with police this week, Castile was overcome by that same sense of hopelessness that he felt when his sister's son died — the same sick feeling he's gotten every time another deadly police incident makes news.

"Is anything ever really going to change?" Castile wondered.

As demands for accountability rang out from Floyd's family, politicians on both sides of the aisle, celebrities and other high-profile figures, Frey called on the county prosecutor to arrest the officer who used his knee to hold Floyd by the neck in a move that is not approved by the agency or the state licensing body.

Visibly emotional, Frey said precedent encouraged him "not to speak out. Not to act so quickly. And I've wrestled with more than anything else in the last 36 hours one fundamental question: Why is the man who killed George Floyd not in jail?"

Yet with several high-profile, fatal police encounters in recent years — along with efforts at reform — some activists couldn't help but feel hopeless. Castile was one of them.

The task force had come up with dozens of recommendations, including required law enforcement training on de-escalation skills and an independent unit within the state Bureau of Criminal Apprehension to investigate all uses of force by police officers that result in death or bodily injury. But in the wake of another tragic death, Castile said Wednesday, the list of proposals felt like just another piece of paper.

"We can come up with all the recommendations in the world. We can make all these new policies. But until people follow these policies, until people use these recommendations and are held accountable when they don't, it ain't going to matter," he said. "It's just a lot of talk, a lot of jibber jabber, and here we go again."

At a police precinct on Minneapolis's south side on Wednesday, officers stood on the roof and fired tear gas and rubber bullets into a crowd of several hundred people, some of whom threw rocks and bottles at the police. Looting was reported at a Target store, adjacent to the precinct, and at least one man was seen running down a street carrying a flat-screen television, but there appeared to be no attempt by police to intervene.

Arradondo acknowledged the "trauma" and "pain" in the community over Floyd's death and said his department was doing its best to respect the "First Amendment" right of those who had gathered. But he warned the department would not tolerate unsafe behavior. "There's space to be respectful, but we cannot have members of our community engaging in destructive or criminal types of behavior," he said.

Community activists who have sought change following incidents such as the fatal shootings of 24-year-old Jamar Clark in 2015 and 40-year-old Justine Damond in 2017 describe a familiar refrain. There are community protests and support from officials before the old patterns set back in.

"The city council members and the mayor and police chief constantly bemoan what they can't do because their hands are tied by the [police union] contract," said Dave Bicking, vice president of the police accountability and reform group Communities United Against Police Brutality. "But every three years when the contract comes up, they rubber stamp it."

Arradondo on Wednesday said police department reform needs to be viewed "as a marathon, not a sprint." But he acknowledged that one incident could sow doubt.

"That's why I am obligated and dedicated to making sure that each and every day, I act in a way, and our men and women act in a way, that builds that trust that garners that credibility and legitimacy," the chief said. "And then also, when things go wrong, that we own it."

Benjamin Crump, an attorney for the Floyd family, said that without public pressure, he feared authorities would try to sweep the incident under the rug. But he said that with the video, "you can't deny truth that you witness with your own eyes."

The chain of events that led to Floyd's death began just after 8 p.m. Monday, when a Cup Foods employee called 911, suspecting that Floyd had tried to use a fake $20 bill. Security footage provided to The Washington Post showed squad cars pulling up outside the corner store in the southern part of the city.

Minutes later, after a brief struggle, two officers removed a handcuffed Floyd from a vehicle and placed him against the wall of a business. He was questioned and taken across the street, stumbling and still handcuffed.

What happened next was captured in the now-viral video that would set off fresh outrage in Minneapolis and across the United States. "I cannot breathe," Floyd said, repeatedly, as an officer kept him pinned by the neck to the ground. An increasingly distraught group of onlookers pleaded with the police, telling them, "Get off his neck!"

A fire department report said paramedics arrived to find Floyd was unresponsive and had no pulse. Several bystanders told them the police had "killed that man."

At least two of the officers have been involved in previous use-of-force incidents, including fatal ones. Chauvin, a 19-year veteran of the force, shot people in at least two prior incidents, including a 2006 fatal shooting of a stabbing suspect, according to a database maintained by Communities United Against Police Brutality. Thao was a defendant in a 2014 lawsuit alleging excessive use of force, according to court records. The city later settled the complaint for $25,000.

Mylan Masson, a former officer who ran police training at Minnesota's Hennepin Technical College until 2016, said that because of problems including people getting hurt, that form of restraint is no longer approved by the Peace Officer Standards and Training Board. Now, officers using a knee restraint are told to put the pressure between the shoulder blades rather than on the neck. Watching the video, she said, "it kept getting worse and worse."

"You only use your force until the threat is stopped," she said. "Once the threat is stopped, you discontinue your force. He was not thrashing around. He wasn't really moving. He was trying to breathe, is what he was trying to do at first."

She said she wanted to know all the details before weighing in on whether the officers should be arrested.

But to family of Floyd, a "gentle giant" and father of two who worked security at a local restaurant, there was no question. In interviews on Tuesday and Wednesday, they said they believed he had been murdered.

"I would like for those officers to be charged with murder," his sister Bridgett Floyd said during a Wednesday appearance on NBC's "Today" show. "Because that's exactly what they did. They murdered my brother. He was crying for help."

Her words echoed those of a cousin, Tera Brown, who on Tuesday told CNN's Don Lemon that "what they did was murder."

"And almost the whole world has witnessed that," she added, "because somebody was gracious enough to record it."

On Tuesday night, officers in riot gear responded to protesters with tear gas, flash-bang devices and nonlethal bullets after some in the large crowd shattered windows at the police department's Third Precinct and vandalized cars, according to local media and images shared online. The police response drew criticism from some who drew a contrast between the demonstrators in Minneapolis and the heavily armed protesters who gathered at state capitols in recent weeks to demonstrate against shutdown measures enacted amid the novel coronavirus pandemic.

Among those condemning the police response was Rep. Ilhan Omar (D), whose district includes Minneapolis.

"Shooting rubber bullets and tear gas at unarmed protesters when there are children present should never be tolerated. Ever," she tweeted. "What is happening tonight in our city is shameful. Police need to exercise restraint, and our community needs space to heal."

Responding to the criticism, Frey said Arradondo had told him that he "could not run the risk of one tragedy leading to another," adding that he supported the police chief.

In the neighborhood where officers detained Floyd, a spokesman for the family that owns Cup Foods said Wednesday that they had offered to cover the expenses of Floyd's funeral.

"We feel so remorseful that this happened," said the spokesman, Jamar B. Nelson.

Among the hundreds of people at the intersection to continue protesting Floyd's death, there was a sense of despair at the fatal cycle that seemed to play out again and again between people of color and law enforcement in the city.

There was little faith in the idea that anything would change — no matter how swiftly the city had moved to terminate the four officers involved or how much the mayor and other elected officials spoke out against such behavior.

"[The police] think of us as less than animals, and that's the way it has always been," said Claudette White, who is black and has lived in the neighborhood on and off for decades. She raised her kids to be cautious of the police, warning them they wouldn't be treated the same as white people, and even now, at 69, she continually worries something might happen to them. "I don't see things getting better, not in my lifetime," she said. "I think it's only going to get worse."

Years ago, she'd run into a burning house to save a neighbor's life. And now, she teared up thinking of Floyd lying on the street here, his neck compressed by the knee of a police officer, as he gasped for air and called out for his mother.

"I wish I'd been here," she said. "They probably would have shot me, but I would have done something."

____

Shammas reported from Washington, and Bellware from Chicago. The Washington Post’s Tim Elfrink and Allyson Chiu in Washington contributed to this report.