Hurricanes near U.S. coast forecast to worsen and multiply due to global warming

The 2020 hurricane season is notable for the number of storms that developed in the mid-latitudes right off the U.S. coast. And it may become more frequent as climate change alters hurricane behavior,

The 2020 hurricane season may be best remembered as the one that spawned so many storms that forecasters ran out of names and had to resort to Greek letters. But it is notable for another disquieting reason: the number of storms that developed in the mid-latitudes right off the U.S. coast. While this is not unheard of, it is unusual. And it may become more frequent as climate change alters hurricane behavior, according to a new study.

The vast majority of hurricanes develop from disturbances that blow off the west coast of Africa on the prevailing winds. They form into low pressure systems and storms as they cross the tropical Atlantic into the warmer waters around the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico.

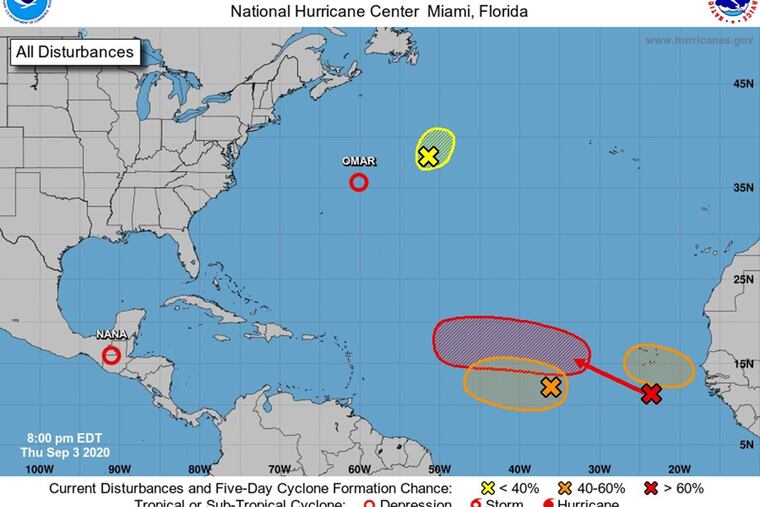

But this season, six storms - Arthur, Bertha, Fay, Omar, Isaias and Sally - either formed or strengthened in the coastal region between Florida and the Carolinas. Four of them had nontropical origins:

- Tropical storms Arthur and Bertha both formed in May, before the official June start of the Atlantic hurricane season, off the Florida and South Carolina coasts.

- Tropical storms Fay (July 9) and the short-lived Omar (Sept. 1) both formed off the North Carolina coast.

Meanwhile, hurricanes Isaias (July 30) and Sally (Sept. 14) were the remnants of African waves that strengthened in the warm waters just south of Florida before taking their respective routes: Isaias north to New England, and Sally across Florida into the Gulf of Mexico, where it strengthened and caused disastrous flooding in several Southern states.

"Frontal origins of tropical cyclones are not that unusual, but four times so far this season is unusually often," Ryan Truchelut, chief meteorologist at WeatherTiger, a private weather forecasting service, wrote in an email, referring to storms with nontropical origins. "The culprit is much warmer than average waters in the western Atlantic, coupled with generally lower than average wind shear in the same area driven by the tilt into La Niña" (a periodic weather system that creates favorable conditions for hurricanes)."

The warming water Truchelut refers to is largely a result of climate change, the buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that has heated the oceans 0.41 degrees Celsius during the last 50 years. Warm water is the main fuel for tropical storms and hurricanes.

While it's impossible to predict future trends from a single hurricane season, scientists can take historical and other data and run models to get a glimpse of what the future may bring. That's what Kerry Emanuel, a climate scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, did in a new peer-reviewed study in the American Meteorological Society's "Journal of Climate."

The study found that the probability has increased for future storm generation off the North American coast. Emanuel, a leading authority on hurricanes, has been modeling climate change's impact on tropical cyclones for three decades.

In the study, Emanuel used nine climate models from the latest generation of a global modeling project called CMIP6, coordinated by the World Climate Research Program. In a process called "downscaling," he tightened the spatial resolution of hurricanes by embedding a specialized model used to forecast them. When he ran the resulting program, it showed how hurricane characteristics evolved as carbon was added to the atmosphere at the rate of 1 percent annually.

The results "show an increase in both the frequency and severity of tropical cyclones, robust across the models downscaled, in response to increasing greenhouse gases," the study says, noting a particularly strong increase off the coast of North America.

Although the majority of storms in the study did not make landfall, those that did were exceptionally powerful and potentially destructive.

The storms in the study also showed an increased potential to stall over a specific area, a scenario that can lead to flooding rains and destructive winds, which occurred with hurricanes Harvey in 2017, Florence in 2018, Dorian in 2019 and Sally this year. This finding builds on previous studies that drew similar conclusions.

The paper also notes that rapid intensification, the sudden acceleration in a hurricane's intensity, "increases rapidly with warming." This does not bode well for coastal communities, because "adaptation to changes in infrequent events (like hurricanes) is notoriously flawed and unduly influenced by politics and special interests," Emanuel wrote, citing Gilbert M. Gaul's 2019 book "The Geography of Risk: Epic Storms, Rising Seas, and the Costs of America's Coasts."

The study's finding that storm frequency will increase is not in consensus with existing studies, noted Timothy Hall, a senior research scientist at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies. But the increase in hurricane intensity is.

"If you look across a swath of studies he's a bit of an outlier" on storm frequency, Hall said. "However, there is pretty good consensus that there will be an increase in intensity."

Like Emanuel, Hall believes society is not preparing itself for a more stormy future. "The awareness of the impact of climate change on hurricanes, human society and infrastructure is really lagging where the science is," he said.

Hall should know; he specializes in the hazards tropical cyclones pose to coastal communities and consults with risk mitigation analysts and public policy groups.

For Emanuel, any debate about storm frequency is a distraction because the increase in frequency is dominated by weak storms that usually do not do much damage.

"What society should be concerned about is the frequency of high-category hurricanes, categories threes, fours and fives," he said. After all, it only takes one major storm to devastate a community forever.

- - -

Korten is a journalist based in Miami and the author of “Into the Storm,” about Hurricane Joaquin and the sinking of El Faro in 2015.