Pennsylvania criticized for how it handles elder abuse cases

A Pennsylvania state watchdog agency is criticizing how county-level agencies investigate thousands of complaints about elder abuse and how the state ensures complaints are investigated adequately.

HARRISBURG, Pa. (AP) — An internal Pennsylvania state government watchdog agency is criticizing how county-level agencies investigate thousands of complaints they receive about elder abuse and how the state ensures complaints are investigated adequately.

Among the shortcomings identified by the Office of State Inspector General were failures by some county-level agencies to properly investigate complaints under timelines required by state law and inadequate staffing of the state office that monitors those agencies.

A six-page summary of the report released this week also said investigative practices aren't standardized across counties and it criticized training requirements for caseworkers as far too weak, particularly compared to model states.

Complaints can involve physical abuse, self-neglect, or financial exploitation and Pennsylvania, like other states, is seeing a fast-growing number of complaints that has forced some counties to hire more caseworkers to keep up.

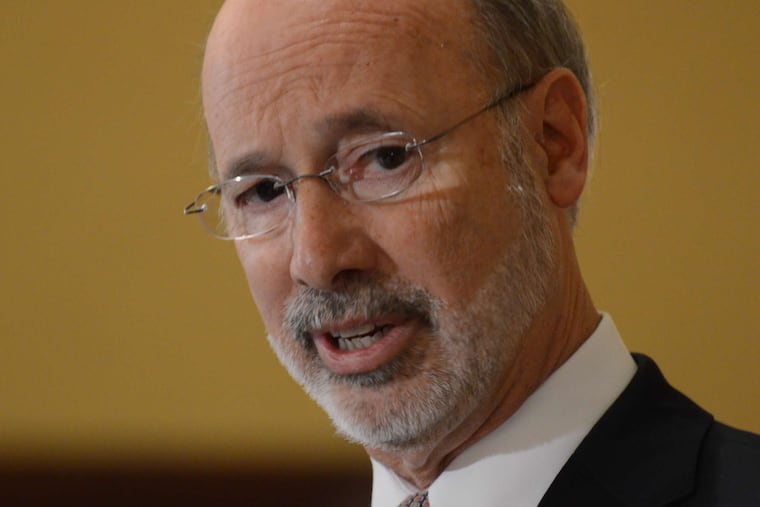

Gov. Tom Wolf's administration said it has begun to address the report's findings. In the days before it released the report's summary, Wolf cleared out the top two officials in his Department of Aging, which oversees what is called protective services for people who are 60 and older.

The Pennsylvania Association of Area Agencies on Aging, which speaks for the 52 county-level agencies, said those organizations and the Department of Aging "have made significant improvements" since the inspector general's investigation began.

Wolf's administration is not releasing the inspector general's full 24-page report, although his office said that, in releasing the summary, it is being more transparent than the state's long-standing practice of keeping such reports confidential.

The Associated Press in 2017 reviewed hundreds of pages of Department of Aging records and found the performance of the county-level agencies varied widely. The department's reviewers had told some counties that they had failed, sometimes repeatedly , to meet regulations and expectations over properly investigating complaints and logging casework.

At times, department officials had demanded that a county agency ensure the safety of an alleged victim.

The AP also found wide disparities in how often a county deemed a complaint to be worthy of a full investigation and action. The details of complaints, investigations and the identity of the person whose situation is in question are kept secret.

Caseworkers handled nearly 32,000 calls about potential elder abuse in the 2017-18 fiscal year, according to department records, up from 18,500 five years earlier.

Since 2011, the Department of Aging has been led by people who came from a county-level agency. The department does not report to an outside, independent agency or reviewer.

Should a county-level agency fall down on the job, the department reserves the right to take over the task, or fire it and hire some other agency. It has never done that.

Wolf said last month that he is tapping Robert Torres to lead the Department of Aging after 14 months as Wolf's acting secretary of state. If confirmed by the Senate, Torres would become the first secretary of aging in eight years who did not come from one of the county-level agencies that the department oversees.

Wolf will nominate his first secretary of aging, Teresa Osborne, for a lower-paid job on the Civil Service Commission. Asked about the reason for leaving, Osborne, in an email, did not bring up the inspector general’s report, and said she is looking forward to her new job on the commission.

Wolf’s office said the inspector general’s report had nothing to do with Osborne’s removal. The administration said it ended the employment of the Department of Aging’s No. 2 official on Friday, but declined to comment on the reasons.

Frustrated by shortcomings they had identified in elder-abuse investigations, department staff in 2017 began grading counties on a more aggressive compliance schedule.

Since then, better than one third of the 52 county-level area agencies on aging have at one point received a substandard red or yellow rating, according to information from the department.