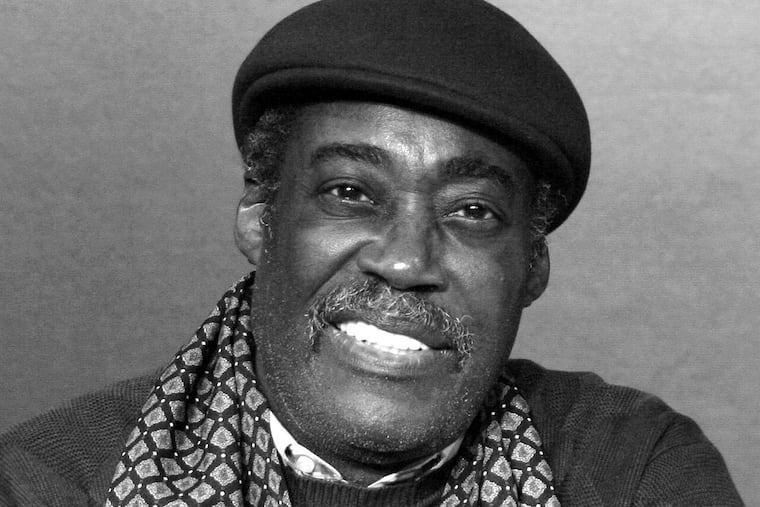

Charles H. Fuller Jr., Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and Philadelphia icon, has died at 83

“His genius was not in just in the small aspects of theater. He was a true literary giant,” said Temple professor Molefi Asante, who wrote a book about the playwright in 2015.

Charles H. Fuller Jr., 83, a Philadelphia-born playwright whose A Soldier’s Play won the Pulitzer Prize in 1982, died Monday, Oct. 3, in Toronto, his son said.

David I. Fuller said his father had developed dementia in the last year or two, but he did not provide a specific cause of death.

Mr. Fuller was the second Black American to win the Pulitzer for drama. Charles Gordone, who won for No Place to Be Somebody in 1970, was the first.

The Negro Ensemble Company debuted A Soldier’s Play in November 1981 in an off-Broadway production. Directed by Douglas Turner Ward, the play featured Denzel Washington and Samuel L. Jackson in small roles before they were household names.

In 1984, Mr. Fuller’s adaptation was made into a film, and renamed A Soldier’s Story, which received an Academy Award nomination for best picture. Mr. Fuller also earned an Oscar nomination for his screenplay.

A Soldier’s Play examined the complex and layered issues about racism and in-group conflict among Black soldiers set at a segregated Army base in Louisiana during World War II.

In interviews, Mr. Fuller said he used his experiences growing up in a tough North Philadelphia housing project and his military service in telling the searing drama.

A Black sergeant was murdered and the investigation points to white soldiers, the Ku Klux Klan, and, eventually, one of his fellow Black soldiers.

“The best way to dispel stereotypes and massive lies is telling something as close to the truth as you can,” Mr. Fuller once told Newsday.

Mr. Fuller and his second wife, Claire Prieto-Fuller, lived in Canada for the last four years, his son said.

Mr. Fuller’s first wife, Miriam Nesbitt, to whom he was married for 44 years, died in 2006.

David Fuller said his father told him he was moving to Canada, where his wife is from, because “I want a change of scenery, to get the creative juices going.”

Molefi Kete Asante, a Temple University professor, however, said Mr. Fuller told him he was going to Canada because the Philadelphia theater community had not shown him the respect his work deserved and rarely produced his plays.

“He told me something similar to what James Baldwin once said: ‘You never get the credit you deserve in this country if you’re a Black writer.’”

Mr. Fuller was aware and pleased that the Kimmel Center will present A Soldier’s Play early next year, from Jan. 24 to Feb. 25, his son said.

The play itself took nearly 40 years to reach Broadway, in February 2020, where it won a Tony Award for best revival.

“He was ecstatic to see it on Broadway,” Asante said. “It was a powerful revival. I was there with him [on opening night].

“He was so in his element. He was a very noble man. He was really iconic in the theater world. He was a tall, handsome man, with an incredible mind and a deep sensibility regarding humanity and human nature, and always willing to tell truth to power.”

Asante said Mr. Fuller felt hurt when leading Black writers, among them the late poet and writer Amiri Baraka, were critical of A Soldier’s Play because it pointed to the idea that a Black soldier might have murdered the sergeant.

“What many of the Black dramatists were saying was ‘This was in Louisiana in the 1940s. Why make the killer a Black man?’“

Mr. Fuller was interested in the psychological aspects of internalized racism that led to violence and class strife between Black people, Asante said.

One of Mr. Fuller’s plays, Zooman and the Sign, dealt with a Black father’s anguish to find the person responsible for killing his 12-year-old daughter, who was struck by a stray bullet while sitting on the family’s front porch.

The father’s grief turns to anger after learning that some neighbors who witnessed the shooting are too afraid to talk to the police. The play won an Obie Award in 1981.

“His genius was not in just the small aspects of theater. He was a true literary giant. He was a philosopher, and he thought deeply about these issues.” said Asante, author of The Dramatic Genius of Charles Fuller.

Kimmika Williams-Witherspoon, an associate professor of theater at Temple, said Mr. Fuller told her that A Soldier’s Play had not made it to Broadway years ago “because he refused to change the last line of the play.”

That last line was: “You’ll have to get used to Black people being in charge!”

Williams-Witherspoon described him as a kind, thoughtful man when she invited him to speak to her students: “The generosity of spirit he brought was just amazing.”

She said he was one of the first Black Americans to start a theater group in North Philadelphia, the Afro-American Arts Theater in Philadelphia, which he cofounded in 1967.

When David Fuller was 11, one of his classmates asked him why his father never wrote comedies.

After school, he went to his father: “I said, ‘Dad, why don’t you write any comedies?’ He sat me down and said, ‘Son, I don’t write comedies because the plight of Black people in this country is no laughing matter.’

“Of everything he has said to me, I remember that the most,” David Fuller said.

The family was living in the Yorktown neighborhood of in North Philadelphia at the time but moved to Northeast Philadelphia later that year.

The Mural Arts Program dedicated a mural of Mr. Fuller, painted by Ernel Martinez, at 1631 W. Girard Ave., on July 30, 2021.

Mr. Fuller was born in Philadelphia on March 5, 1939, and was the eldest of four children. His father, Charles Fuller Sr., was a printer. His mother, Lillian Anderson Fuller, was a homemaker.

After graduating from Roman Catholic High School, Mr. Fuller attended Villanova University but left in his junior year to join the Army.

He served for three years, in Japan and South Korea‚ until 1962. Upon returning to Philadelphia, he resumed his college studies at La Salle University.

He worked for a time as a Philadelphia housing inspector when he first began to write plays at night for the theater group he started.

After the success of A Soldier’s Play, he received honorary doctorate degrees from La Salle, Villanova, and Chestnut Hill College.

Funeral services have not yet been announced.

In addition to his son, Mr. Fuller is survived by his wife, a sister, four grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. Mr. Fuller’s older son, Charles Fuller III, died in 2013.