Kathy Boudin, Weather Underground outlaw and Bryn Mawr graduate imprisoned after fatal heist, dies at 78

She spent 11 years on the run after a 1970 bombing and participated in an armed robbery in 1981 that left two police officers and a guard dead. She became a criminal justice scholar after her parole.

On the morning of March 6, 1970, Kathy Boudin had just finished showering when a shrapnel-packed dynamite bomb fashioned by her radical colleagues in the militant left-wing Weathermen group accidentally detonated in the basement of the Greenwich Village townhouse where they were staying.

Their plan had been to attack an officers’ club dance at an Army post in New Jersey, part of the Weathermen’s effort to bring home the war in Vietnam.

The explosion left three Weathermen dead and the townhouse at 18 West 11th Street in ruins, and Boudin staggered naked out of the rubble, along with another uninjured woman. A neighbor gave clothes to Boudin, who fled amid the chaos.

Boudin — a descendant of prominent leftist intellectuals and five years out of the elite women’s college Bryn Mawr — became one of the country’s most wanted outlaws. She spent the next 11 years in hiding with other militants, by then calling themselves the Weather Underground, in urban safe houses and remote farmsteads.

Using aliases and stolen credit cards, they periodically surfaced to plant bombs at government and corporate buildings. They hit nearly two dozen targets, including a bathroom in the U.S. Capitol in 1971 and another in the Pentagon in 1972.

After the townhouse disaster, the Weather leadership sought to dial back the violence, and no one was injured or killed in the subsequent bombings, which were carried out at night largely as symbolic acts against recognized superior forces.

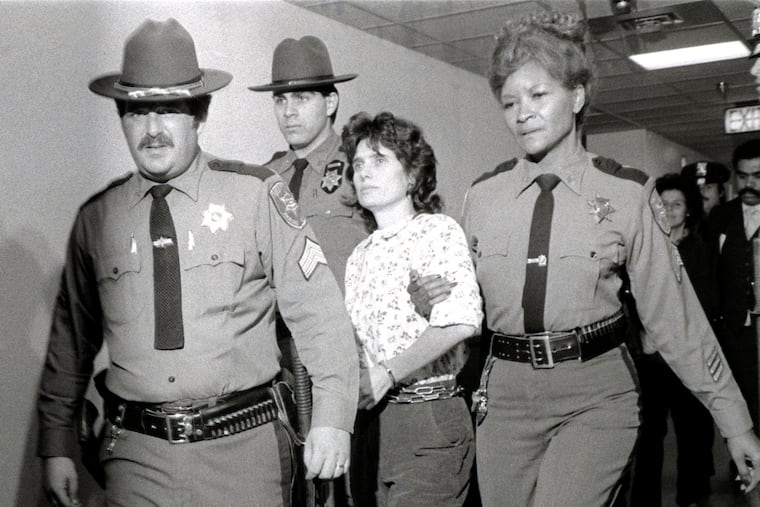

Boudin’s life as a fugitive came to an end on Oct. 20, 1981, with her arrest in a botched $1.6 million robbery of a Brink’s armored truck in suburban New York. Two police officers and a Brink’s guard were killed in shootouts with violent Black nationalists she had joined.

Boudin, who pleaded guilty in 1984 to murder and robbery charges in the incident, was paroled in 2003 and later became a criminal justice scholar at Columbia University. She died Sunday in New York at the age of 78. The cause was cancer, said Rachel Marshall, a spokeswoman for Boudin’s son, Chesa Boudin, the San Francisco district attorney.

While acknowledging the terrible consequences of the townhouse explosion and the Brink’s robbery and killings, Boudin contended that she was only peripherally involved in both.

She said she never engaged in bombmaking at the townhouse, although Boudin family biographer Susan Braudy reported that Boudin had checked out a library book on the chemistry of explosives shortly before the fatal blast.

In the Brink’s case, she said, she was only a passenger in a getaway vehicle. But during her 2003 parole hearing, she said she had fully supported the robbery — a statement that victims’ relatives viewed as a cynical ploy to curry favor with the parole board by showing that she was taking responsibility for her actions.

Kathy Boudin (pronounced boo-DEEN) was born in Manhattan on May 19, 1943, and grew up in an elite social milieu. The family’s 19th-century brownstone played host to a salon of the city’s leftist intellectuals, and she attended liberal Greenwich Village schools and dined at home with noted writers and political activists.

Her father, Leonard Boudin, was a civil liberties lawyer whose client roster included entertainer Paul Robeson, among other figures called before the House Un-American Activities Committee during anticommunist witch hunts of the 1950s. He later represented the government of Cuban dictator Fidel Castro, civil rights activist Julian Bond, anti-Vietnam War protest leader Benjamin Spock, and Pentagon Papers leaker Daniel Ellsberg. Her uncle I.F. Stone was a famed muckraking journalist.

The Boudin household was emotionally turbulent. Kathy’s mother, poet Jean Roisman, twice attempted suicide and spent years in psychiatric hospitals. Leonard was a serial womanizer not above assignations with Kathy’s friends.

The Boudins’ privileged daughter began to rebel. She protested air-raid drills in high school and agitated in favor of wage hikes for the Black campus maids at Bryn Mawr. (The latter activity backfired when the school phased out the maids’ jobs.)

She studied abroad in the city then known as Leningrad and graduated from Bryn Mawr in 1965 with a major in Russian literature. Then she immersed herself in the rat-infested squalor of a Cleveland slum as a community organizer for an offshoot of the leftist group Students for a Democratic Society.

“It was thrilling,” she told the New Yorker in 2001. “I felt like I was learning about the realities of class, of poverty. It was the discovery that there was a whole other world that I was living next to, part of, and didn’t really know about.”

Along with other SDS activists who rejected the peaceful, mainstream anti-Vietnam War movement as ineffectual, Boudin sided with the more violence-prone Weathermen faction when it split from the group in 1969. The new organization took its name from a lyric in the Bob Dylan song “Subterranean Homesick Blues”: “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.”

Boudin helped organize and participated in the October 1969 Days of Rage action, in which scores of helmeted militants smashed the windows of cars and store fronts in downtown Chicago. She and other Weathermen allied themselves with the Black Panthers and other groups that law enforcement authorities considered subversive.

Although the Weathermen movement began to implode after the Vietnam War ended, Boudin declined for years to surface.

“The very status of being underground was an identity for me,” she told the New Yorker. “It was a moral statement. Three years, five years, eight years, ten years, eleven years — that was who I was. … In the world we live in, you make a difference in a small way, but it feels like you are doing something. But I was making a difference in no way, so then I elevated to great importance the fact that I was underground.”

After another sectarian split within the Weather Underground, she sided with the May 19th Communist faction, which then joined forces with the Black Liberation Army, itself an armed offshoot of the Black Panthers.

During the 1981 robbery of the Brink’s armored truck in Nanuet, N.Y., Boudin and her boyfriend, David Gilbert, waited in a nearby getaway truck while two other May 19th participants sat in a second vehicle. BLA members then attacked the armored truck, setting off shootouts with Brink’s guards and then with police.

The bandits loaded cash from the armored truck into the getaway vehicles but were stopped moments later by additional police. Boudin and others were arrested at the scene. Several BLA members slipped away, but they were caught days or weeks later.

Boudin pleaded guilty to robbery and a single count of felony murder in an agreement carefully fashioned by her father and her attorneys, including civil rights lawyer William Kunstler and her father’s law partner Leonard Weinglass.

Under New York law, a participant in a felony — the armored truck robbery — can be held responsible for any deaths that result. Her attorneys successfully argued that Boudin had surrendered before the two police officers were killed and thus could be considered responsible only in the death of the Brink’s guard.

She was sentenced to 20 years to life, while other defendants, including Gilbert, received much longer terms. At the time of the robbery, she and Gilbert had a 14-month-old son, Chesa. When Boudin went to prison, she turned Chesa over to Weather leaders Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers.

Dohrn and Ayers moved to Chicago, embarking on a conventional life in academia and raising Chesa with their own two children. He completed law school, moved to California, where he entered political life, and was elected district attorney of San Francisco in 2019.

In addition to her son, survivors include Gilbert, described in a statement as her life partner; six grandchildren; Chesa’s two brothers, Zayd and Malik Dohrn; and her brother, Michael Boudin, a lawyer who, breaking with family tradition, is an outspoken conservative. Michael Boudin served in President Ronald Reagan’s Justice Department and was appointed to the federal appellate bench by President George H.W. Bush in 1992.

In prison, Boudin received a master’s degree in adult education from Norwich University in Vermont and taught in a prisoner literacy program. After her parole, she received a doctorate from Columbia University Teachers College in 2007, and a year later, she was appointed an adjunct professor at Columbia’s School of Social Work. Her parole and her academic advancement stirred resentment among the slain officers’ relatives and others. Critics referred to her as “Columbia’s pet terrorist” and accused her of indoctrinating students with leftist propaganda.

At Columbia, she cofounded the Center for Justice, whose goals included developing ways to ease inmate transition to life outside prison.

Explaining the decision to hire Boudin, the university cited her expressions of remorse for her role in the Brink’s case and newspaper interviews in which students applauded her unusual teaching perspective.

Boudin, a published essayist and poet, once composed this declaration for a writing workshop in prison: “If only there were a place where the living and the dead could meet, to tell their tales, to weep, I would reach for you — not so that you could forgive me, but so that you could know that I have no pride for what I have done, only the wisdom and regret that came too late.”