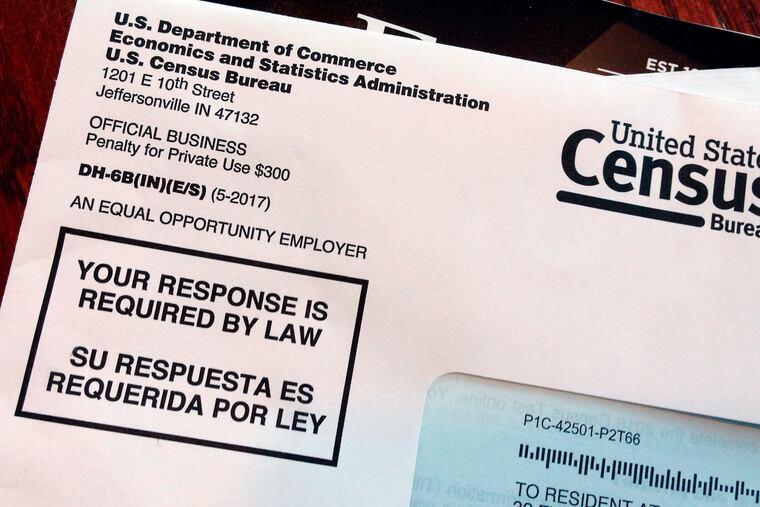

Census 2020: How going digital could undercount those who need the census most | Opinion

Widespread lack of trust, combined with cynicism about the government’s motives, raises doubt that the U.S. Census Bureau can meet its goal of collecting more than half of all 2020 Census questionnaires online.

Tanya, an African American woman in her 30s who lives in Philadelphia, doesn’t own a computer and exclusively uses her phone to access the internet. She is wary of job opportunities that require her to submit applications online. The same is true for credit card approvals. “I’m suspicious of that process … giving out my name, my number,” Tanya said.

Tanya (whose name has been changed to protect her identity) is one of 79 cell-mostly internet users we interviewed this year about online privacy and mobile-phone practices. The people we spoke with expressed concern about providing personal information through a mobile internet connection, and frequently shared anxieties about government surveillance. During our conversations, smart-phone internet users told us they believe government officials collect information for “control” and to see “what’s going on with the masses.”

These privacy concerns stand to have major implications for the 2020 Census — the first ever to be completed largely online. The federal government plans to begin rolling out its tally in January, with most households expected to respond by April. The bottom line? The around $800 billion the federal government assigns according to census results, going toward programs for public housing, highway construction, education and health care. During fiscal year 2016, Pennsylvania received more than $39 billion to support 55 programs, an amount guided by 2010 Census data, according to researchers at George Washington University.

Our study findings suggest that it will be difficult to accurately count people who rely on mobile internet access. A widespread lack of trust, combined with cynicism about the government’s motives, raises doubt that the Census Bureau can meet its goal of collecting more than half of all 2020 Census questionnaires online.

The Census Bureau has an optimistic plan: First mail out access codes and letters encouraging people to complete the questionnaire online. The government hopes 50 to 60 percent of the public will submit electronically during this phase. A small group of respondents will initially receive paper surveys, according to the internet connectivity where they live and other demographic characteristics, and paper follow-ups will be sent to those missed. But cell-phone-dependent folks, especially those without stable addresses, risk falling through the gaps — thanks to technical issues familiar to cell phone users (screen size, data limits) as well as a particular distrust of sharing their information via phone.

The shift toward gathering responses electronically is part of a broader effort to slash data collection costs. The agency says that various technological innovations — including redesigning how it compiles addresses, and using administrative records as sources of household information — will save an estimated $5.2 billion.

» READ MORE: A civil rights fight could shift political power away from Philly and North Jersey

But the effects of this switch won’t land equally. “Smart-phone-only internet users,” who own a mobile device but lack residential broadband service, could be left out. These people typically belong to demographic groups expected to be undercounted — people of color and low-income Americans. According to an analysis conducted by the Urban Institute, the 2020 Census could undercount black and Hispanic/Latinx individuals by more than 3.5 percent.

While all U.S. adults are increasingly likely to access the internet through their phones, skin color and income largely determine whether someone depends on a mobile device to go online. About 24 percent of Hispanics and African Americans rely on mobile devices for internet access, compared with just 12 percent of white Americans, according to a Pew Research Center report released in June.

Income is another factor. One-quarter of U.S. adults earning less than $30,000 per year lack a home broadband connection but own a smart phone, the Pew Research Center found.

When respondents to the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey used a mobile device in 2015, they were significantly more likely to quit the survey before completing it, compared with PC users, according to the bureau’s own evaluation. Data collected were also less accurate than when respondents used a computer.

Logistical hurdles to completing the census on a cell phone are fairly easy to predict: Respondents might be stopped by data limits, or forms that are tough to read on different screens. Then there are the distractions created by the flurry of alerts, text messages, and calls.

But, our research reveals, cell-phone users may face other more subtle barriers. The people we interviewed generally knew that government agencies collect and use their cell-phone data. They also recognized that participating in programs designed to assist low-income families, such as free school lunches for their kids or living in subsidized housing, increased their exposure to government surveillance.

The public view of such surveillance takes a hit when data collected for public programs are used in problematic ways. Dominating recent headlines are stories about Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents using facial recognition technology to mine millions of driver’s license records — without motorists’ knowledge. Data breaches by the government have permeated the public consciousness since at least 2013, when Edward Snowden leaked classified documents revealing that the Department of Homeland Security routinely tapped into Americans’ emails, texts, and Google searches.

The Census Bureau promises anonymity and confidentiality for questionnaire responses. This guarantee, however, faces an uphill battle countering pervasive skepticism toward giving the government personal information. “Every time … I do something [that] involves me putting a debit card number in, or my Social in … before I even do it, I ponder on it, I think about it, like, do I really want to do this?” a man in Philadelphia told us. Another interviewee cautioned that sharing personal information over a mobile device could enable the government to “monitor you for drug activity or something.”

The angst we heard while interviewing cell-mostly internet users — who already feel marginalized — suggests this population will be reluctant to participant in the 2020 Census, unless census workers can bridge major trust gaps. During a focus group hosted in North Philadelphia, a man told us that the government and corporations ask him for information “like it’s no big deal, like we know each personally… but I know [they’re] going to screw me over somehow.”

Ironically, these roadblocks could perpetuate structural inequalities already imperiling people who, arguably, most need services funded based on the census.

Gwen Shaffer is on faculty at California State University Long Beach and chairs the City of Long Beach’s Technology and Innovation Commission. Jan Fernback is on faculty at the Lew Klein College of Media and Communication at Temple University.

The Philadelphia Inquirer is one of 21 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push toward economic justice. See all of our reporting at brokeinphilly.org.