Philadelphia must imagine its next 250 years

Nearly 1,000 Philadelphians have shared ideas about what we wish Philadelphia to be in 2276 — but the current PH.LY draft is open for one final round of feedback before the Semiquincentennial year.

Thirty years ago next February, the world’s first high-profile competition between human and machine intelligence took place in Philadelphia.

IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer faced world chess champion Garry Kasparov at the still-new Pennsylvania Convention Center. It was timed with the 50th anniversary of the unveiling at the University of Pennsylvania of ENIAC, the world’s first supercomputer, and a reminder that Philadelphia once led the world into the computer age.

Back then, artificial intelligence felt distant. Today, it feels existential.

As we prepare to host the nation’s 250th anniversary in 2026, I’ve been asking: In a city so rich in history, are we still interested in the future?

How it started

This spark began in 2023, during a reporting project on economic mobility called Thriving that Technical.ly — the news organization I founded and lead — published with support from the William Penn Foundation, the Pew Charitable Trusts, and the Knight Foundation. Our newsroom followed 10 Philadelphians for a year to produce an award-winning audio-documentary and hosted a dozen focus groups across the city.

One Brewerytown resident said something that inspired a previous op-ed I wrote for this paper: “Leaders here talk a lot about hundreds of years in the past, but nobody is looking very far in the future.”

Across this region — in boardrooms, nonprofits, universities, and regional corporate offices — too many leaders manage the wealth and institutions created by past entrepreneurs, but too rarely invent anything new. We fight over what exists instead of building what’s next.

The Semiquincentennial is our chance to prove we can balance our past, present, and future.

Why this matters now

My career has been spent listening to and challenging the inventors, entrepreneurs, and civic leaders shaping tomorrow’s economy. They act while others analyze.

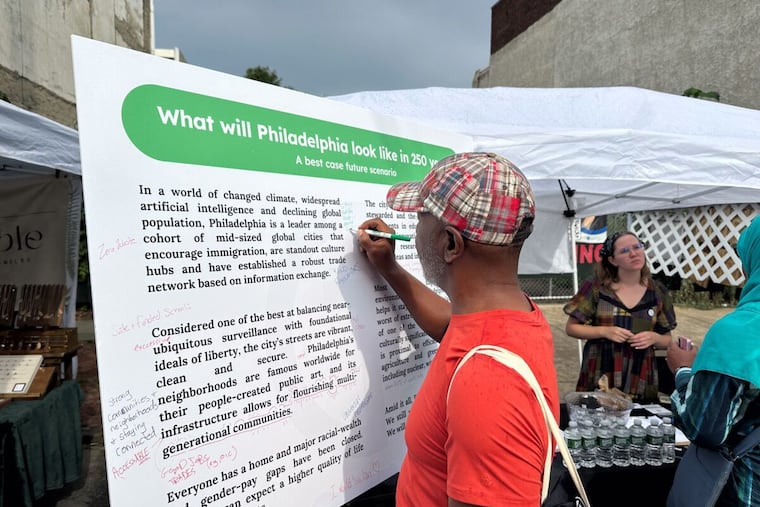

In that spirit, we spent two years developing a vision for Philadelphia 250 years in the future. Nearly 1,000 Philadelphians have shared ideas at festivals, community events, and small-group gatherings. The current draft, open for one final round of feedback at Ph.ly, isn’t a plan but an invitation — a shared view of what we wish for our descendants in 2276.

Philadelphia must keep people — not technology, not incumbency — at the center of our future.

The coming decades could bring population decline, climate strain, and sweeping technological change. Yet, many local leaders still struggle to plan even years ahead.

During a recent private discussion I moderated inside one of our city’s impressively preserved old buildings, a longtime civic leader cited Philadelphia’s poor economic mobility ranking. I reminded him that the same research, with the same warning, was released a decade ago. Why didn’t we plan to make changes then?

He assured me this time would be different.

Philadelphia’s past points forward

Philadelphia’s breakthroughs have nearly always come from outsiders who pushed past local gatekeepers.

Stephen Girard, a French immigrant dismissed by elites, built a shipping and banking fortune, stabilized the nation’s finances, and endowed Girard College.

The Drexel family’s daring banking experiments helped fuel the Industrial Revolution before founding the school for engineers.

Albert Barnes saw beauty where Philadelphia’s art establishment did not.

ENIAC’s inventors, John Mauchly and Presper Eckert, were a little-known physics professor and a 24-year-old grad student whose entrepreneurial efforts were blocked locally, presaging Silicon Valley.

Most recently and famously, Nobel laureate Katalin Karikó’s mRNA research that led to the rapid-fast, lifesaving COVID-19 vaccine response was commercialized in Boston, not here.

The pattern is clear: Visionaries choose to live in Philadelphia, yet often get ignored, if not outright blocked, by local institutions. That’s no way to secure the next 250 years.

There are signals of change.

I take inspiration from bold efforts to build, including the Delaware waterfront and the cap of I-95. In the 2010s, Philadelphia’s technology sector earned initial, if timid, attention from successive mayoral administrations and civic leadership — and a half dozen tech unicorns were born.

» READ MORE: Philadelphia is too often in crisis mode, which does nothing to stop future crises | Opinion

That tech community helped inform this multiyear vision statement project, which received $75,000 from a funders collaborative activating Semiquincentennial efforts, including the William Penn and Connelly Foundations. The city’s 2026 planning director, Michael Newmius, has been supportive, urging us to listen to residents and avoid undue filtering.

Over two years, we’ve tabled at community events, hosted discussions, and led working sessions. The result isn’t mealymouthed or filtered by incumbency; it has grit and humanity — like Philadelphia itself.

You can read the draft vision at Ph.ly and in the article box in this op-ed. We’re collecting one final round of feedback this fall, and we’ll incorporate what we can. We’re accepting feedback until Dec. 1.

From conversation to commitment

Our goal is to enshrine the final version of this statement on a physical plaque at a prominent location in the city. We’ll also host a digital version online, paired with voices from residents across the region.

This vision doesn’t prescribe policy, nor make fallible predictions; instead, it offers a shared aspiration, a framework that future leaders can measure their plans against.

In its early drafts, the statement imagined a green-energy Philadelphia with climate-adaptive agriculture, abundant public art, thriving multigenerational neighborhoods, and a culture that “exports ideas and imports opportunity.”

Over subsequent versions, the specifics were removed to reflect the long time horizon, but the spirit remains: Philadelphia must keep people — not technology, not incumbency — at the center of our future.

The Semiquincentennial should celebrate our history — I personally cherish it. I was a historic Old City tour guide for a year, and my daily bicycle commute to the Technical.ly newsroom past Independence Hall reminds me what endurance looks like.

But if we only admire our past, we’ve missed its key lesson. Philadelphia is strongest when we pair cobblestones with invention’s spark.

Read the vision at Ph.ly. Critique it, add to it, make it better. May it inspire Philadelphians for generations to keep building, not just preserving.

The Kasparov-Deep Blue rivalry is remembered as the moment a machine beat a human genius. But that was the rematch. The first contest — the one held here in Philadelphia — ended with the human winning. Let’s make sure that’s still true for our city.

Christopher Wink is the publisher and cofounder of the news organization Technical.ly.