Blowing the whistle on a sex abuse deal | Opinion

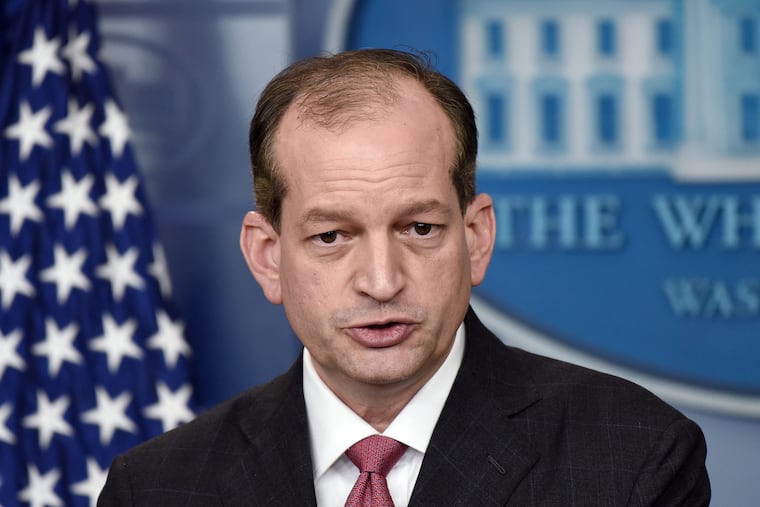

On Thursday, a federal judge ruled in a civil lawsuit that Acosta (reminder: Trump’s Labor secretary) broke a victims’ rights law in concealing the particulars of Jeffrey Epstein’s deal from the girls who gave evidence.

Over the last two decades, nearly 100 women told authorities all about sexual crimes allegedly committed by the hedge-funder Jeffrey Epstein.

Epstein was a friend of Donald Trump, Bill Clinton and many other men in high places.

Most of the women —girls at the time — at first identified themselves as Jane Doe. But now, many are using their real names. This is how the traumatized take power back: They go on the record. They take on the hardest of moral challenges. They become whistleblowers. They are eyewitnesses who know the truth and they are willing to speak openly about it.

Women now in their 30s — notably Michelle Licata, Virginia Roberts, Courtney Wild and Jena-Lisa Jones — are the central whistleblowers in the Epstein case. Finally, the government isn’t going easy on Epstein. No matter that he’s rich, and no matter that he’s connected.

Twelve years ago, despite masses of corroborating evidence and the statements of the Jane Does, federal prosecutors under then-Miami U.S. Atty. Alexander Acosta — now President Trump’s Labor secretary — handed Epstein a sickly-sweet sweetheart deal.

The multimillionaire pleaded guilty to two negligible charges of soliciting prostitution in state court and paid restitution to dozens of his victims. In exchange, according to the plea agreement, he and “any potential co-conspirators” received immunity from potential federal charges that could have carried a life sentence. And instead of being sent to state prison, Epstein served his grueling 13-month sentence in a private wing of the Palm Beach County Jail, with work release privileges of up to 12 hours a day, six days a week.

But that was then.

On Thursday, a federal judge ruled in a civil lawsuit that Acosta (reminder: Trump’s Labor secretary) broke a victims’ rights law in concealing the particulars of Epstein’s deal from the girls who gave evidence. The judge gave prosecutors 15 days to come up with a settlement; it’s possible that Epstein’s plea deal could be overturned entirely.

An emboldening victory for the whistleblowers, right, even if it did take years? In fact, the women had already been emboldened. In a blockbuster series last November, they spoke to reporters Julie K. Brown and Emily Michot at the Miami Herald.

Since 2008, the culture has shifted, and the women in the Epstein case are acting out the change: The kind of corruption at the heart of their experience is now far too cartoonishly obvious to be meekly accepted as the way of the world. Sunlight, in the form of whistleblowing, disinfects.

To this end, Licata opened the curtains wide. In the Miami Herald, she described the winding staircase in Epstein’s Palm Beach house that led to a dark room with shag carpeting and a pink-and-green sofa. She saw a towel-clad man with gray hair, she says, who sexually assaulted her, and then dismissed her. She and the others initially thought they were just being paid to give a rich man a massage.

Wild corroborated the M.O., and what she added must have taken even more guts. “By the time I was 16, I had probably brought him 70 to 80 girls who were all 14 and 15 years old,” she admitted. Whistleblowers get their authority from being close to crimes they are revealing, so close that they are often implicated in the wrongdoing. It takes courage to own up to it. Although whistleblowers are rarely prosecuted, they pay a price.

The girls who implicated Epstein were threatened by private investigators hired to dig dirt on anyone who called out his trafficking operation.

Bill Browder, who relentlessly blows the whistle on the murderous corruption of the Kremlin, has exposed himself to a vicious smear campaign. His lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, who helped Browder investigate Russian misdeeds, was detained and died in prison, allegedly beaten to death. A Russian court found both men guilty of tax fraud _ Browder in absentia; Magnitsky posthumously. The Kremlin keeps trying to get Browder extradited.

But Browder, now a British citizen, has the money to pay for security, lawyers and a platform. By contrast, many of the women who testified against Epstein are ex-runaways. They surely can’t afford his kind of private security detail and crisis-management teams.

That doesn’t stop them. Wild and Jones gave accounts that matched Licata’s memories, down to details of the staircase, the room and the sexual abuse. Roberts described being “lent out” for sex to other men, including academics and politicians.

“Stand in your truth” may be a cliche of the #MeToo movement, but it suggests the steadfastness required to speak honestly about the kind of abuse of power exemplified by the Epstein case and in so many other realms _ at the southern border, in the White House, in the halls of Congress. What we need is direct testimony, in public, complete with numbers, names, dates, addresses and the color of the couches and the shag carpet.

But there’s one question about abusers in high places that even the sharpest first-hand witnesses can’t answer. Virginia Roberts phrased it best in an interview after the Miami Herald series was published: “How did you get into that position of power in the first place if you’re this disgusting, evil, decrepit person on the inside?”

Virginia Heffernan writes opinion pieces for the Los Angeles Times, where this piece originally appeared.