It’s time to nominate more defense attorneys to be judges | Opinion

Greater professional diversity is needed on the bench, writes Keisha Hudson. Without it, judgments from our courts disproportionately reflect the viewpoints of prosecutors.

Coming to America as a 15-year-old from a humble background in Jamaica, I discovered wonderful things about my new country, but also things that were disturbing.

My mother, one of those incredibly strong female role models who define my life, had emigrated for better opportunities, and, like other immigrants to the United States, her tenuous economic toehold in New York City permitted my father and the rest of us to follow.

I adapted to a new culture, despite its overwhelming newness. I negotiated a new American me, attending Cornell University, graduating from Cornell University Law School, and starting out here in Philadelphia as a public defender.

Along the way, I learned that many people — people of color, people that looked like me, immigrants with little or no English, and all those whose lives are crimped by scarcity — were treated differently.

Today, as the chief public defender in Philadelphia, I’m confronted by even sharper differences in court decisions meted out in this state, and across the nation, because of a lack of professional diversity on the benches in our courthouse.

A study published in 2019 found that former prosecutors outnumbered former defense attorneys on the federal bench by a ratio of 4-1.

» READ MORE: Race awareness is not race discrimination, even when it comes to the Supreme Court | Opinion

Most Americans do not think about the criminal legal system much at all, lulled by simple slogans like “Do the crime, do the time” or “No money for bail, then stay out of jail.”

Then what to make of an impoverished teenage mother with no criminal background held in Montgomery County on $50,000 cash bail for a month because of a fight with another young woman? No lawyers were present at the hearing to determine bail, and while incarcerated, she was given nothing to preserve her breast milk or access to nurse her baby.

Compare that to the situation of Roger Stone, the billionaire friend of former President Donald Trump, convicted of lying to Congress, tampering with evidence, and threatening a witness, but back on the street after paying a $250,000 bail.

If our experiences affect our judgments, then the judgments from our courts today disproportionately reflect the viewpoints of prosecutors who represent the government’s point of view.

President Joe Biden is assiduously appointing more diverse judges on lower-level courts; nearly a third of his nominees have been former public defenders. And he promises to nominate a Black woman to the U.S. Supreme Court, which would bring a welcomed, new perspective to the high court.

The professional diversity of a civil rights attorney or a public defender would counter the weight of the prosecutors now there.

Public defense lawyers are on the front line of democracy’s judiciary system.

“If our experiences affect our judgments, then the judgments from our courts today disproportionately reflect the viewpoints of prosecutors who represent the government’s point of view.”

As the manager of nearly 250 public defense attorneys who ensure that no defendant is denied the right to an attorney, I know that front line, because we see the impact of law on ordinary citizens.

Public defenders hear firsthand the stories and circumstances that lead to criminal activity, note the pressure on defendants to accept inequitable solutions, and see the fallout of harm that the government’s neglect of poor people and communities of color has on them and our nation.

Yet, despite the representation we provide, structural inequities based on race and lack of wealth continually impact how justice is dispensed. The result: jails and prisons filled with a disproportionate number of Black and brown folk.

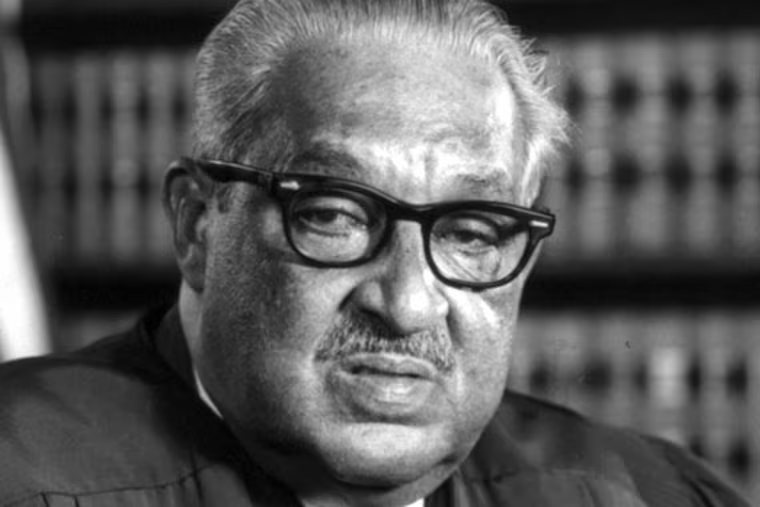

Not one justice on the U.S. Supreme Court has worked as a criminal defense attorney since Justice Thurgood Marshall retired in 1991.

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, the first woman on the high court, praised Marshall’s perspective and its impact on the high court: “His was the ear of a counselor who understood the vulnerabilities of the accused and established safeguards for their protection … at oral arguments and conference meetings, in opinions and dissents, Justice Marshall imparted not only his legal acumen but also his life experiences.”

A Biden commitment to appointing more justices from the ranks of Marshall and the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who was a civil rights lawyer, would begin to equalize the balance between the most vulnerable citizens and the most empowered.

Keisha Hudson is the chief defender of the Defender Association of Philadelphia.