My school created a new curriculum integrating vaccine education. Others should follow our lead. | Opinion

At Belmont Charter High School, we teach about vaccine safety in science, math, social studies, and English.

Even though the CDC has endorsed the COVID-19 vaccine for all school-age children, debates around vaccines and their efficacy persist. As educators, we are left to grapple with the needs of the many people who have legitimate reasons for hesitating to embrace the vaccine while prioritizing the safety of our community.

To provide the most appropriate level of support and respond to our students’ needs, and to do so without a political agenda, we have to first lean in and listen to what our communities are telling us. At Belmont Charter Network, meeting students and families where they are is the foundation of our work.

Over the last several months, we’ve experimented with strategies to combat vaccine hesitancy among the families whose students attend schools in the Belmont Charter Network. We have implemented a comprehensive vaccination education campaign to ease lingering uncertainty in our community. We believe this is the best way to navigate this tumultuous time in history, by helping students and their families learn how they can best protect themselves. I’m sharing how we did this in the hopes that other educators might learn from our example and use these strategies to combat vaccine hesitancy in their own communities.

To make sure our students feel empowered and informed, we created an entirely new curriculum integrating vaccine education.

With an abundance of information — and misinformation — currently circulating from online sources, our English language arts department teaches students how to discern credible sources on medical information. First, students submitted their thoughts and concerns about the vaccine, and are now digging through sources to determine if those concerns are founded. Our social studies curriculum considers the history of vaccines in the U.S. and previous pandemics, focusing on the disproportionate impacts upon Black and brown communities. As part of that, we examine the Tuskegee study to understand why some people continue to be apprehensive of the medical field.

» READ MORE: Helping overcome vaccine hesitancy was their goal. The surprise? Who was the problem.

Our science classes examine how viruses spread, and the history of mRNA. (Our students have been impressed to learn that a female scientist — living in our area! — has been working on this research for decades.) Finally, our math classes analyze statistics about vaccine effectiveness and its side effects, comparing the percentage rates in other countries and how that correlates to their positivity and hospital rates.

Rather than tell students what to think, these courses equip them to make informed decisions — a skill we want them to carry throughout their lives.

“Rather than tell students what to think, these courses equip them to make informed decisions — a skill we want them to carry throughout their lives.”

As part of this campaign, we’ve held multiple listening sessions featuring local doctors from St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children for our students’ caregivers. This allowed families to ask questions and voice concerns among a safe, familiar group. Knowing that Black patients’ concerns are often met with skepticism and bias from the medical community, these ongoing sessions are key to building trust.

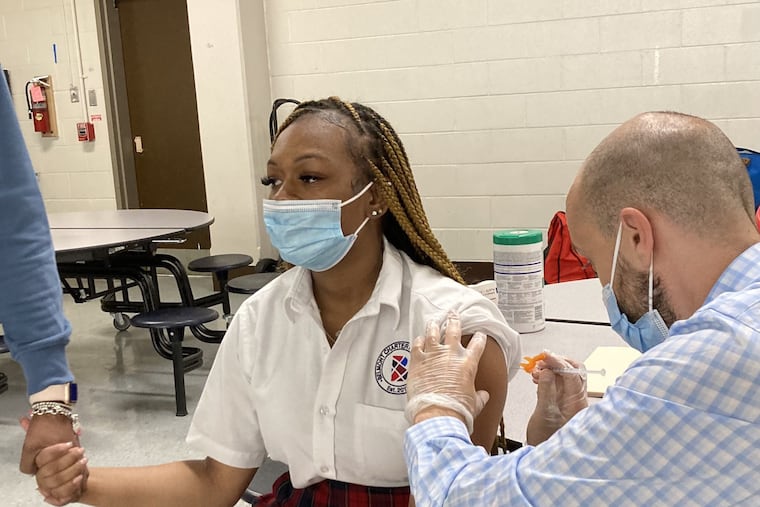

And while we are still in pursuit of increasing the number of vaccinated students, we recognize this is a long-term effort, and our faculty is approaching this topic with sensitivity and tolerance. About 50 of our high school students signed up for our first vaccine clinic this past fall, and we’re hearing from more and more students that they are seeking it through other vaccine clinics. We have received additional requests to host another clinic on our grounds (which we are actively planning).

As with education, our approach to public health should not attempt to conform to a one-size-fits-all model, such as vaccine mandates. Although they may provide a quick fix, vaccine mandates cannot replace the importance of giving individuals the agency to make choices for themselves and apply their lived experiences. While pundits in Washington, D.C., have turned vaccine and mask mandates into a political fight, community schools like BCN are working hard to empower students and families with the tools to make their own decisions.

Education and public health shouldn’t be political. Together, we must think through different community-focused solutions. We must engage in dialogues, present facts to one another openly, see our shared humanity, and respond with empathy. Empowering our education and health systems, instead of mandating policies that fall on one line or the other, is the only way we are going to emerge from this crisis.

LaShaya Duval Shepherd is the head of school at Belmont Charter High School. She previously was an assistant principal at the School District of Philadelphia.