Why we need to celebrate and protect our Black election officials

As primary day approaches, I think of my grandparents — and of the Black election officials around America for whom the evolution of Black representation in our democracy is personal.

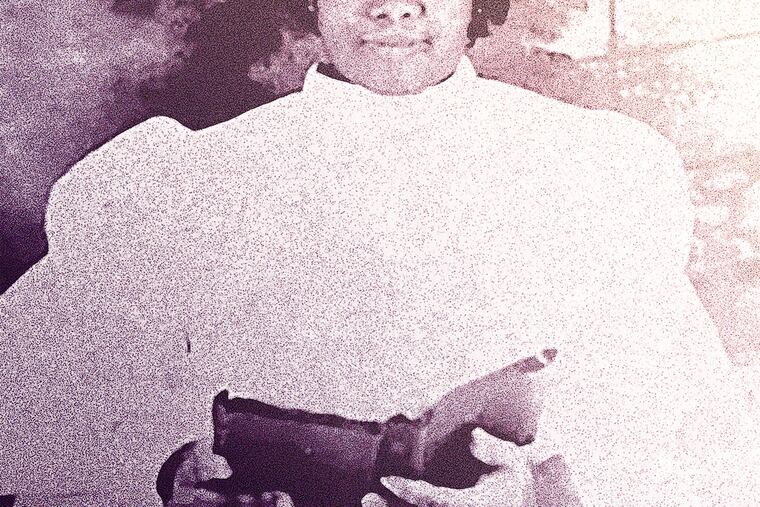

My grandmother, Carrie L. Williams, a teacher, was one of the first Black people to vote in rural Bertie County, N.C. She registered during a time in the state’s history where Black people were required to pass a literacy test, and my grandfather, who never attended formal school, could not join her in casting a ballot.

Just a few decades later, I became the director of election operations in North Carolina.

I wonder if Grandma Carrie could have imagined when she was headed to the ballot box for the very first time that one day her granddaughter would be helping to run elections in the very same state — working like many other Black election officials and poll workers to ensure that all eligible citizens, regardless of race, can participate in a truly representative democratic society.

As primary day approaches, I think of my grandparents — and of all the other Black election officials around America for whom the evolution of Black representation in our democracy is personal.

They, like me, promote fairness and equity in voting in some of the same jurisdictions where registrars of old once discriminately administered those tests. Sadly, there are some in this country who do not recognize the heroic efforts of these election officials and have subjected them to threats, intimidation, and harassment. This behavior is a threat to our democratic society and must be addressed at all levels of government.

Election officials are responsible for voter registration, voting, and the certification of elections. They train poll workers and oversee proper maintenance and security of the voting systems and other election technology. Mental duress and the threat of physical harm impact their ability to carry out these critical tasks. A survey of local election officials by the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law showed more than three-quarters of them feel that threats against election officials have increased in recent years.

In fact, 30% of survey respondents reported being abused, harassed, or threatened because of their job as an election official. In addition to threats of bodily harm, the intimidating behavior directed at Black election officials or election workers has also at times been racist.

My experience as an elections administrator and my family history are the reasons why I joined the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections. It’s a cross-partisan group of experts in elections administration and law enforcement that supports policies and practices that protect voters and election workers from violence, threats, and intimidation.

For example, one way states can help keep election workers safe is by allowing people working in election administration to keep personal identification information — like their address — private, as a defense against threats. California, Colorado, Michigan, and Washington are among the states that have either adopted or proposed legislation for programs that protect the personal information of election officials and other public servants. Pennsylvania should consider allowing election officials to do the same.

30% of survey respondents reported being abused, harassed, or threatened because of their job as an election official.

Local, state, and federal governments can also ensure that election officials have the resources they need to physically secure their offices and the elections they run. Earlier this year, the federal government took an important step by requiring that Pennsylvania and all states spend at least 3% of funds received in fiscal year 2023 from the Homeland Security Grant Program on election security.

When I first heard Grandma Carrie’s story as a child, my young mind thought this family history occurred back in the days of slavery. But the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was enacted only five years before I was born. As recently as 58 years ago, election officials of the Jim Crow era administered literacy tests and collected poll taxes from Black citizens who wanted to vote. These registrars, whose faces undoubtedly lacked substantial melanin, were the gatekeepers of America’s whites-only democracy.

Following a lot of bloody Sundays, water brigades, jailings, lynchings, and two pivotal federal acts in 1964 and 1965, there were fewer blatant obstacles to voter registration allowing Black citizens, regardless of literacy, to more easily participate in all aspects of the democratic process, including its leadership and oversight.

I now understand how rare — and recent — my grandmother’s historic accomplishment was, as well as the unfairness of my grandfather’s plight.

Although Grandma Carrie died a few years before I was born, I am certain she would have understood the significance of my career.

Following my work in North Carolina, I later became the chief election official for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Like other Black election officials, I worked to preserve what she and others fought so hard to earn.

We are especially mindful of the solemnity of our civic and constitutional responsibilities because we realize the struggles that led to our enfranchisement and our ability to hold our positions. Job satisfaction stems not from exclusion, but rather inclusion of all citizens in a truly representative democratic society.

But we still have a long way to go.

In the past, Black people were attacked for simply requesting access to the ballot box; today, Black election officials are being unjustly attacked for administering access to free, fair, and secure elections for all citizens. Black election officials, like all election officials, must be honored, respected, and protected.

Veronica Degraffenreid is a member of the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections and senior manager of strategic partnerships at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law. She is the former Pennsylvania acting secretary of the commonwealth and the former director of election operations for the North Carolina State Board of Elections.