School choice has not cured Philadelphia’s ailing system | Opinion

A recent study suggests charter schools lead to more segregation.

Exercising “school choice” has increasingly become the norm in Philadelphia, where many neighborhood schools have been struggling and under-resourced for decades. Over 70,000 students in the city are opting to attend charter schools; tens of thousands more attend district schools other than their neighborhood schools. Many other families opt out of public education for private and religious schools, sometimes with taxpayer-subsidized scholarships.

Proponents of “parental choice” often argue that it is the best strategy for ensuring equal educational opportunity for underserved students. Providing more choices, in this view, means more equity – the opportunity for every student to have access to a quality public option. So there are calls to create more charter schools and more slots for students within them.

A study of charter schools in Philadelphia published by the Education Law Center earlier this year is a stark reminder that many parents don’t get to choose and that ultimately it may be the school and not the parent doing the choosing. More charters and more slots haven’t cured an ailing school system.

This is not to discount the successes we know exist for students in many city charters. But Philadelphia’s 22-year history of rapid charter expansion coupled with inadequate oversight is entrenching new inequities in an already unequal landscape.

Sometimes the problem is blatant discrimination: For instance, a recurring pattern we see among families who contact us is charters telling students with disabilities, after they have been accepted, “We cannot serve you.” As public schools, charters are prohibited from discriminating against students with disabilities. And yet, we see this pattern persist.

Sometimes the obstacles to enrollment are more subtle; for example, enrollment documents may only be available in English. The results, however, are clear. The population of economically disadvantaged students is 14 percentage points lower in the traditional charter sector (56%) vs. the district sector (70%). And, the percentage of English learners in district schools (11%) is nearly three times higher than in traditional charters (4%), with nearly a third of traditional charters serving no English learners.

Few of the special education students in traditional charters are from the disability categories that typically are most expensive to serve. And, the vast majority of traditional charter schools serve student populations that are two-thirds or more of one racial group – a significantly higher degree of segregation than in district schools.

In short, the city’s traditional charter schools (excluding “Renaissance” charters charged with serving all students from a catchment area) disproportionately enroll a student population that is more advantaged than the students in district-run schools; as a sector, charters are shirking their responsibility of educating all students.

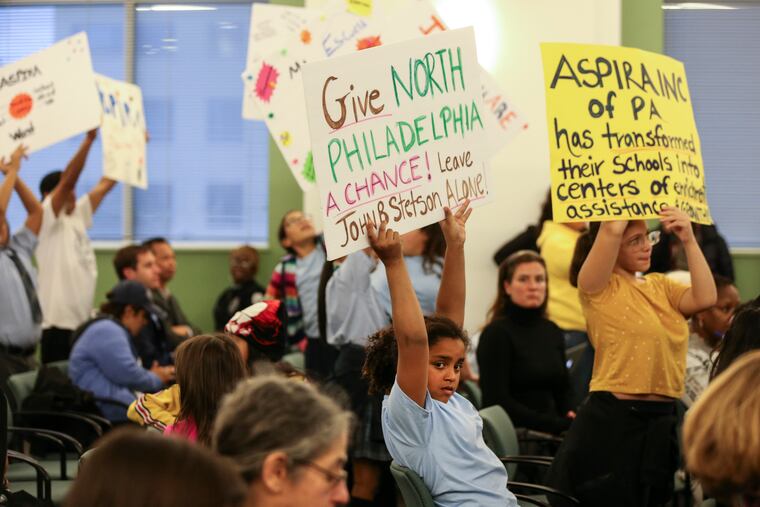

» READ MORE: Philly school board to vote on ending charter agreements for two Aspira-run schools

Policies promoting choice and charter expansion have failed to ensure that schools funded with taxpayer dollars are free from discrimination and accessible to underserved student populations. Charter expansion, when combined with many charters serving a relatively more advantaged student population, undermines equity and exacerbates resource challenges for district schools.

Moreover, a great deal of energy in both sectors goes toward battling over shares of a state funding pie that is much too small. Philadelphians should instead be united in demanding that state officials fix Pennsylvania’s broken school funding system – one with such severe inequity and inadequacy that we and our partners are arguing it is unconstitutional in a lawsuit against the state.

Of course, not all charter schools have practices that exacerbate inequity. Also, district schools are by no means free of barriers to equal access. The Education Law Center has for years raised concerns about denial of access to selective admissions schools for students with disabilities and English learners. But exclusionary practices at some district schools are not a justification for allowing unequal treatment to spread across the charter sector.

It is not too late to demand stronger rules ensuring fairness in how parental choice operates. The Pennsylvania Department of Education is launching a rule-making process for charters that could be a vehicle for new equity guidelines. Those rules will need to be enforced by districts and the state.

In the meantime, let’s pause on expanding “choice” while we put guiderails in place. That work should be one piece of a multipronged strategy that moves us toward great, well-resourced public school options in every community for all of our children.

Deborah Gordon Klehr is executive director of the Education Law Center-PA, a nonprofit, legal advocacy organization with offices in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, dedicated to ensuring access to a quality public education for all children in Pennsylvania.