As Hall of Fame eludes him again, here’s another way the city can honor Phillies great Dick Allen | Opinion

Perhaps it's time for the City of Murals to create another one to recognize a pioneering Black player who marched to the beat of his own drum, writes Dave Caldwell.

Five days before my 10th birthday, my dad and I were among 8,615 fans to attend a Phillies home game at dingy Connie Mack Stadium against Cincinnati. I still have the 25-cent scorecard. The Phillies scored three runs in the bottom of the eighth to topple the Reds, 5-3.

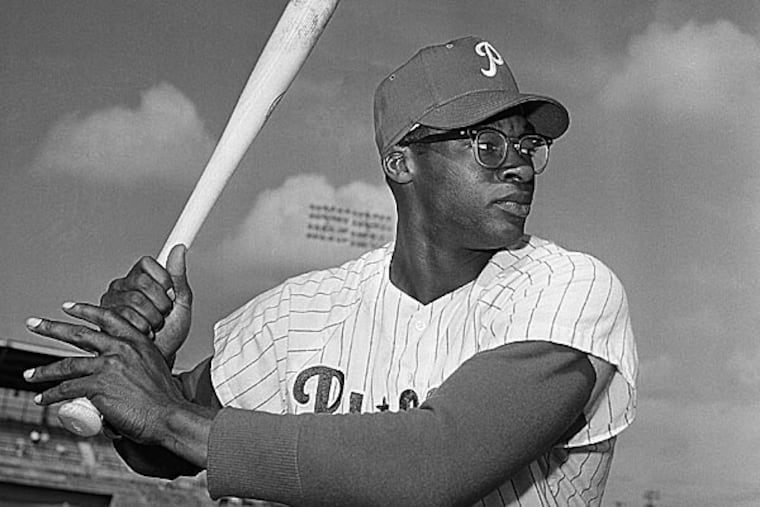

The Phillies’ first baseman that night, Aug. 2, 1969, was the 27-year-old slugger Dick Allen, who went 1 for 3, drawing an intentional walk and scoring the Phillies’ final run. On the scorecard cover were two blank spaces, for the most popular and most valuable Phillie. With my free red scorecard pencil, I scrawled in Allen’s name (referring to him as Rich, as he was known then) in both spaces.

He was a ballplayer who was larger than life, which was why I and many others my age were so disappointed to learn that Allen failed to make the Baseball Hall of Fame on Dec. 5. The Golden Days Era committee kept him out by one lousy vote, for the second time!

His value was so obvious to kids like me in the stands; as an adult, I’ve come to appreciate him even more. As a 10-year-old, I thought Allen was cool because he wore a red batting helmet while playing first base. I played first base, and I wished I could wear a batting helmet.

As an adult, I grew to realize why Allen wore a batting helmet in the field (because racist fans had thrown flashlight batteries at him), or why he scrawled cryptic messages in the infield dirt as he played first base (because he desperately wanted out of town).

» READ MORE: Phillies legend Dick Allen misses election to Baseball Hall of Fame by one vote

He had a poor relationship with sportswriters (who, coincidentally, are the gatekeepers for the Hall of Fame) during his first stint in Philadelphia in the 1960s, and many fans who cheered his home runs also unleashed racist taunts and booed him. “The people in this town like to boo,” he said, “but I just play as hard as I can and don’t listen.”

He was the National League Rookie of the Year in 1964 — the year the Phillies crumpled down the stretch and missed the World Series. His story had a lot of jagged edges, and some of his controversies were self-generated, but he was his own man. Isn’t that like Philadelphia?

Allen died in December 2020 at the age of 78, and surprisingly little has been left behind to mark his time on earth, especially in Philadelphia, where he played for eight memorable and often tumultuous seasons. The Phillies retired his jersey number, 15, three months before his death, but outside of that Allen is hardly commemorated at all.

His likeness does appear on the eight-story Phillies Mural, at the corner of 24th and Walnut Streets, completed in 2015 by the prolific muralist (and lifelong Phillies fan) David McShane.

But the depiction of Allen there is relatively tiny, and he is one of 30 players and managers (plus the Phillie Phanatic) included. In his artist’s statement, McShane wrote that Allen and second baseman Tony Taylor, a Cuban teammate, were included to “represent the increasing diversity of players that entered the league during the Civil Rights Era.”

The MuralArts program to which McShane contributes was not necessarily started as a way to pay tribute to people who did something notable in Philadelphia — like Dick Allen — and murals with sports themes comprise only a small portion of hundreds in the city. But perhaps creating a new mural to honor Allen is one way for the city to recognize this idiosyncratic pioneer.

» READ MORE: Dick Allen was Philadelphia’s Jackie Robinson | Opinion

McShane says the process starts by filling out an application on the MuralArts website. More support from a community is beneficial — perhaps, in Allen’s case, the North Philadelphia neighborhood that surrounded Connie Mack Stadium. But it could be anywhere in town.

“Perhaps a local organization or business has a good wall and would be able to host the mural,” McShane says. “Perhaps there are folks or organizations that could potentially help fund with dollars or in-kind supplies or labor. Perhaps there is a local artist who is passionate about creating a mural with that subject. These kinds of things help move mural ideas forward in our application review process.”

Then Dick Allen could actually become larger than life. Finding a wall and painting it would also buy time between now and 2026, when the Hall of Fame folks vote again. Then they could really see what he meant, and still means, to this city.

Dave Caldwell grew up in Lancaster County, graduated from Temple University, and lives in Manayunk. He was a sports reporter for The Inquirer from 1986 to 1995.