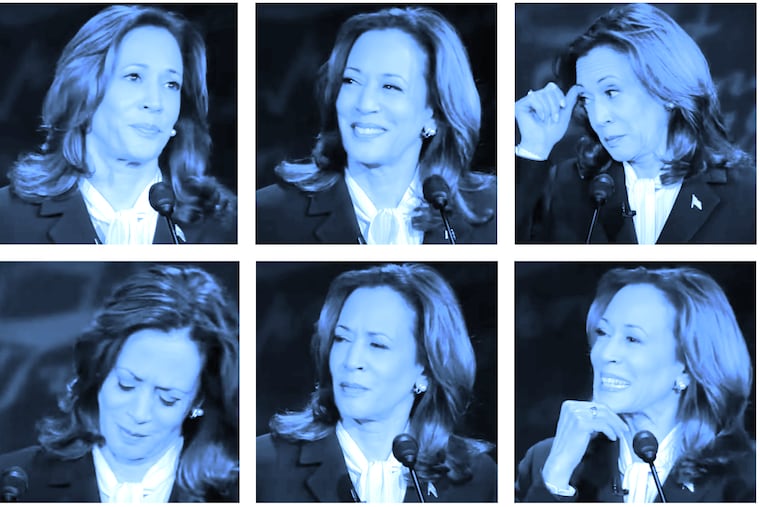

‘Say it to my face’ became ‘say it with my face’ at the presidential debate

What Harris did with facial expressions was a distinctive form of nonverbal speech, a second and simultaneous conversation with some of those watching the debate.

Faces were made.

When the accounts of the 2024 election are written, the things Kamala Harris did on the debate stage with her face last week will merit lasting attention. What Harris did with her face was something more than the alleged “leaky emotions” body language experts are routinely summoned to explain. What Harris did with her face amounted to a distinctive form of nonverbal speech, a second and simultaneous conversation with some of those watching the debate. It was a testament to the advanced but unacknowledged political skill Harris has built, 21 years after she mounted her first campaign.

To be clear, Harris, a college debate club member and seasoned prosecutor accustomed to swaying juries, did all the traditional things one ought to do during a debate. She highlighted differences of opinion and demeanor, driving motivations and priorities. She said things she knew likely to disengage what a friend hilariously described as Donald Trump’s “last hinge.”

» READ MORE: From Kamala Harris, a master class on how to take down a bully | Editorial

But as she did what most on the debate stage would, Harris also spoke to the audience through pronounced facial expressions — widened eyes of surprise, raised eyebrows of disapproval, a hand under her chin paired with a Nancy Pelosi-like sly and chastising smile, and various, almost ineffable faces of disgust, disagreement, and outrage.

What Harris was doing is what experts sometimes call “wink and nod politics,” or “polyphonic communication.” The latter is a term borrowed from the world of music to describe the production of more than one simultaneous note, or in this case, conveying more than one idea at the same time.

Harris didn’t invent polyphonic communication. It’s something on which people who face voluminous constraints often rely to communicate more fully or vent their thoughts in a controlled way. It’s a skill politicians from any historically marginalized group have to master, said Theon Hill, an associate professor of communication at Wheaton College whose research focuses on African American rhetoric in politics, pop culture, religion, and social movements.

It’s shown up in the many local and statewide office contests where Black candidates have become relatively common. And it was perhaps something many people saw but did not quite understand in 2008 when then-presidential candidate Barack Obama spoke to his first mass audience after a terrible first primary debate performance.

The Denver Post tellingly described the first mass audience speech Obama gave after that debate this way: “Barack Obama, fresh from Wednesday’s debate, beleaguered but still standing, acknowledging that he has taken some hits from his opponent, but it’s OK because that’s politics. ... And then he — pay attention now — brushes the dirt off his shoulders.” The writer turned to the urban dictionary to explain that Obama was “brush[ing] off the negative energy of statements made ...”

That was, Hill said, one way of seeing things. But for the hip-hop generation, for many Black Americans, and anyone familiar with Jay-Z’s 2003 hit “Dirt Off Your Shoulder,” Obama was verbally saying he would carry on, it was one debate. But he was saying with a very specific use of his hand and shoulder, “I am humbled but not broken, still a singular figure.”

He was saying, “I know I can’t pay any mind those who would like to see me fail, those who believe I am operating above my station. I have to carry on not in spite of but because of them.” He was saying, “I understand expectations and hopes are high, and that in a country that has never elected a Black president, a resilient mindset matters.”

But it’s important to note here that Harris — who has since childhood identified as a Black woman with Indian heritage — is a Black woman. So the list of acceptable, laudable, or sufficiently decorous public behavior is, for her, long, complex, and often constraining, said Leah Hollis, associate dean for access, equity, and inclusion in the Penn State College of Education. Hollis’ research has centered on workplace bullying and the way race and gender can influence educational experiences.

“I find that Black women are hyper-visible, and no matter what, there is often going to be an issue,” said Hollis, who emphasized she was not speaking for Penn State, but sharing her opinions formed from the findings of her research. “You know you don’t want to be tagged as the angry Black woman. So she had to have a brave and happy face, which is what is often expected from women of color.”

Obama could brush his shoulders off, a bit of self-affirming braggadocio. And Joe Biden was praised when he said, “Will you shut up, man,” to Trump during a 2020 debate.

“There’s a rich history in the U.S. of policing both the bodies and facial expressions of Black people, Black women specifically,” Hill said. “I mean, we can see that in the ways Michelle Obama was constantly analyzed and scrutinized, with [U.S. Supreme Court Justice] Ketanji Brown Jackson, and even in sports with athletes like Serena Williams or Angel Reese.”

What Harris did with her face was as intentional, as strategic as just about everything else she could control on that stage.

From the moment Harris crossed the debate stage to shake Trump’s hand, she set a tone, Hill said. She entered his space when Trump did not, as is customary, meet his opponent in the middle for a handshake. She conveyed, “I can compromise.” And as she introduced herself, stating her first and last name correctly, it all but said, “I’ve told you and America nicely. Now let’s debate.”

“It was almost like this polite aggressiveness and confidence,” Hill said.

When she raised her eyebrows at Trump’s assertions, put her hand under her chin, and elevated those same brows, when she at points laughed, widened her eyes, and shook her head at Trump’s ideas, she was effectively saying to those who read face, “Yes, I, too, think this is outrageous, this is racist, this is irrational, this is not in keeping with American democratic traditions.” But when she spoke, and did so largely with a smile, she offered up some, but critics argue insufficient, policy details. And she demonstrated an acute understanding of the behavioral lines inside which people like her are expected to play.

It was one of those moments that brought to mind what the late Texas Gov. Ann Richards said in her 1988 Democratic National Convention stage speech about the underrecognized skill of Ginger Rogers, a woman who did everything Fred Astaire did, only backward and in heels.

» READ MORE: Black women welcome allies, but we need accomplices | Opinion

“Kamala Harris and that debate is emblematic of how being of color and a woman, you have to be three and four times better,” Hollis said. “It’s clear if it wasn’t for the fact that she was a sitting VP and a crisis after we saw President Biden’s performance [in the previous presidential debate], the stars, the sun, and the mood had to line up for this opportunity to be open to her.”

And what Harris did with her face was as intentional, as strategic as just about everything else she could control on that stage. Those facial expressions were meant to land and stick, if not needle — just like that comment about the size of Trump’s crowds.

If you doubt that, consider the way grids of Harris’ facial expressions have become widespread memes online, still in circulation after an entirely wild and news-filled week. Consider that Trump clocked more talking time than Harris, yet still lost. Consider that contrary to what Trump did after he defeated Biden in the first debate, Trump quickly said there would be no Harris rematch.

Faces — and points — were, indeed, made.

Janell Ross is a reporter based in New York who, among other adventures, has covered politics at every level, including the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections and, years before that, a hotly contested municipal dog catcher race.