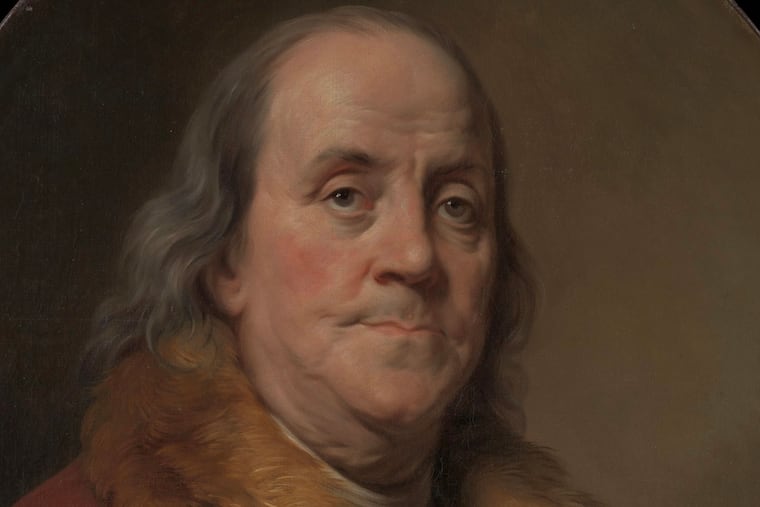

Ben Franklin’s evolution on slavery

The Philadelphian came to see that the ideals he championed — liberty, self-determination, human dignity — could not coexist with human bondage.

Benjamin Franklin’s life was an exuberant experiment in growth.

Printer, scientist, diplomat, statesman — he was a polymath who moved restless and curious across so many disciplines — testing everything, challenging his own assumptions, and always revising his ideas about the world.

But perhaps the most profound transformation he underwent over the course of his fascinating life was a moral one: The evolution from a man who at first was tolerant of slavery to one who became one of its most outspoken opponents.

It is tempting for me, as much as I admire Franklin, to imagine him as a man unequivocally ahead of his time, already carrying the clarity of the abolitionist cause in his youth. But that’s just not the truth. He once owned several enslaved people who worked in his household here in Philly.

And he printed advertisements for slave sales and notices of runaway slaves in his newspaper, at the same time that he was printing opinion tracts against slavery from Quaker abolitionists.

Slavery was woven into the fabric of colonial life, and Franklin, though more intellectually curious than most, was not immune to its compromises.

What makes Franklin’s relationship to slavery so worth telling in this moment is not his early complicity or his final adamant support of abolition. It’s that he changed; that he was capable of change.

Over the course of his many years, he came to see that the ideals he championed — liberty, self-determination, human dignity — could not coexist with human bondage.

Enlightenment philosophy sharpened his thinking. His years in Europe, where slavery was increasingly condemned, widened his moral horizon.

And the American Revolution itself, with its fierce declaration that “all men are created equal,” posed a challenge that Franklin, unlike many of his peers, could not ignore.

By the 1780s, Franklin had taken up the abolitionist cause in earnest. In 1787, he became president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, lending his name and his considerable reputation to the movement.

In 1790, in one of his final public acts, Franklin petitioned the brand-new U.S. Congress to end both slavery and the slave trade as a whole. That Congress, filled with men not yet willing to confront the issue, tabled his petition.

But the symbolic weight of Franklin’s appeal could not be dismissed. Here was the most beloved elder statesman of the revolution, insisting the young nation live up to its own creed.

Franklin’s life reminds us that we do not have to cover up our past, even when it contains grave wrongdoing.

» READ MORE: Vigilance needed if Trump’s attempts to rewrite the history of slavery at Independence Mall persist | Editorial

To look squarely and fearlessly at our history is not to dishonor it, but to use it as a stepping stone to greater and better versions of who and what we can be.

Acknowledging Franklin’s early failings does not diminish his legacy for me. In fact, it expands it, in that it shows he was capable of transcending his own errors in thinking, which is the mark, to me, of true wisdom.

We cannot deny we live with the burden of America’s contradictions, slavery foremost among them. But we also live with Franklin’s example.

He teaches us that it is possible, and, in fact, necessary, to own the full breadth of our history — beautiful and noble, but also fallible and fraught.

To confess our mistakes honestly is the first step in rising above them. That was clearly the hope of the Founding Fathers, and particularly of Franklin in his final years: that the nation would evolve beyond its own sins and grow closer, generation by generation, to the promise of liberty for all.

We do not evolve by forgetting where we’ve been.

I am not ashamed of my country for the mistakes it made as it struggled into being. I am only ashamed of those who, 250 years later, would prefer to hide those mistakes. We do not evolve by forgetting where we’ve been.

A nation, like a person, must face its past with honesty, humility, and integrity if it is ever to grow into the fullness of its promise.

Hillary O’Carroll is a resident of Old City, the dockmaster of Pier 5 Marina, an urban farmer and garden designer, and an avid lover of Philadelphia’s history.